A long term affair with science: Happy birthday Marie Curie

with Brigitte Van TiggelenDownload this episode in mp3 (29.41 MB).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This podcast has a very special connection with the legendary Madame Curie. As most listeners will know by now, I am an academic researcher based in Ghent, Belgium, and my work is funded by one of the Marie Curie Actions, which are European mobility research grants. This grant has changed my life in many ways, and it is meaningful to me that it is named after Madame Curie. Since when I found out that I got the grant, about two and a half years ago, I started educating myself about her work, her lfe, her legacy. I became passionate about Madame Curie and I am particularly happy to bring this special episode of my podcast to you celebrating her birthday, November 7th (1867).

To celebrate her birthday and honour her memory, I have asked a world-class historian of science, Brigitte Van Tiggelen, to join me on Technoculture. Among other appointments, Brigitte is Director of the European Operations at the Science History Institute, Chair of the division of History of Chemistry inside the European Chemical Society, and associate at the Centre d'histoire des sciences et des techniques de l'Université catholique de Louvain à Louvain-la-Neuve, in Belgium.

In November 2019, Brigitte and I met again, exactly a year after our first interview, to record the short clip for EuroScientist.

I spent a delightful hour speaking with Brigitte. Besides honouring Marie Curie on her birthday, we have opened more questions that we have closed: hence I am excited to announce that this episode will have a follow-up, where we will talk about the idea of the "heroic creator", the "solitary genius" in science and research, and how it constitutes a powerful image on which so much of the rethoric around science rests, but also how it underserves the community when it comes to providing realistic role models. Brigitte and I found that Marie Curie, for one, both a woman and an icon, becomes an ever stronger model and a truly inspiring story when she is "given back to herself", when the humanity of her life is portrait for what it was, in its everyday complexity like the lives of all of us. Tune in for the follow-up episode and meanwhile... thank you Marie Curie, and happy birthday!

"One cannot but be struck by the expression of the large, limpid eyes that seem to be following some inner vision." (Marie Curie on her husband, in her book "Pierre Curie")

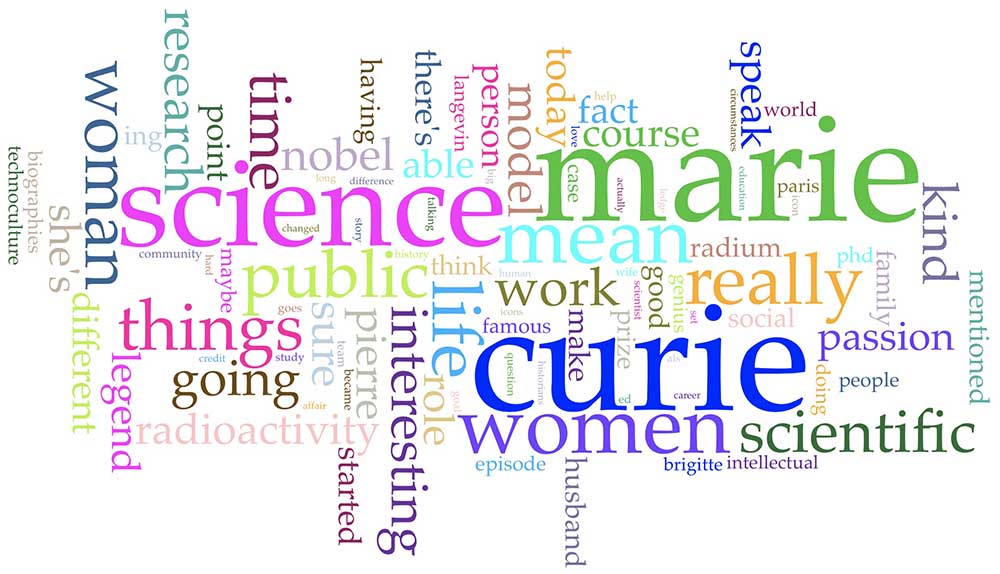

Go to interactive wordcloud (you can choose the number of words and see how many times they occur).

Episode transcript

Download full transcript in PDF (114.62 kB).

Host: Federica Bressan [Federica]

Guest: Brigitte Van Tiggelen [Brigitte]

[Federica]: Welcome to a new episode of Technoculture. I'm your host, Federica Bressan, and today my guest is Brigitte Van Tiggelen, a historian of science who holds several appointments. She is Director of the European Operations at the Science History Institute, Chair of the division of History of Chemistry inside the European Chemical Society, and associate at the Centre de recherche d'histoire des sciences de l'Université catholique de Louvain à Louvain-la-Neuve, in Belgium. Brigitte was telling me a couple of minutes ago that she was reluctant to be introduced just by her titles, especially today, because we speak about Marie Curie, somebody who was withdrawn from the public attention and someone who would certainly not want to be defined by the labels or titles that were attached to her by the external world. But I wanted to make sure that we understand that Brigitte is a historian of science and that she has a specific knowledge in the field of chemistry which is relevant to our topic today, of course, Marie Curie, whom we celebrate on her birthday. She was born on November the 7th, 1867. So let's begin. Welcome to Technoculture, Brigitte.

[Brigitte]: Thank you, Federica.

[Federica]: Whether we know her work and her scientific achievements or whether we know details from her private life or not, we are certainly familiar with her name: Marie Curie, the most famous woman scientist of all times. Why is she so famous? Why is she the icon and the legend in science and popular culture we know today?

[Brigitte]: So first, before we go to the question, 'Why is Marie Curie the most famous scientist?' it might be useful for to remind the listeners what she accomplished during her life. So, everyone knows she got a Nobel Prize with her husband and third person, Henri Becquerel, in 1903 and then another one all by herself in 1911. Her name is also attached in thoughts of everyone to radioactivity, and indeed, she took that as a topic of PhD, and she was the first to really study this phenomenon scientifically, and she was able therefrom to isolate two new elements, polonium and radium, which is also an accomplishment. And later on, when she entered, so to speak, the public sphere and became, as she was still living, an icon, she most of the time was very set trying to take distance with this public animation around her, but on some occasions, she took advantage of it to accomplish things she really cared for. For instance, she went twice on a tour in the U.S. in '21, and then, if my memory is correct, in '23, she went on a tour to gather money to have a radium gram, a gram of radium. The first one was to give to her Institute in Paris and the other one, the second one, was to give the gram of radium to the Radium Institute in Warsaw, where she also had created one. And so there's all kinds of things in which there's a tension between the public figure, what she really accomplished (which was indeed phenomenal), and the, I would say, more intimate figure Marie Curie. And this was complicated by the fact that very early, the legend of Marie Curie started even before she died, so to speak. So she had a very complicated life which, in my opinion, has not yet been fully investigated by historians of science, is that she was living her life while she was already becoming a legend. In some cases, she would take advantage of it, as I said, but in others, she had a lot of trouble to follow, so to speak, the role that she was given by her own legend. So in a way, she is now presented as a role model, and one could almost argue that maybe she had trouble to follow her own role model, so to speak. And I think that those are the things that are really interesting to discuss, especially now in the light of, how do you do research now? How do you publicize research? How do you advertise the research that's done? And how do you climb the ladder in the scientific community? Because this is, after all, the question, you know. How do you become so famous that everyone knows your name, whereas the scientific endeavour, the scientific community is constituted by a long list of people whose name we actually have totally forgotten?

[Federica]: What triggered her notoriety? What started the process that made a legend of her while still alive?

[Brigitte]: So it's hard to really pinpoint a moment, but surely when Pierre and Marie Curie received the Nobel Prize, and the news was broadcasted in 1903, surely that was the point where they became public persons. And, of course, at that time they became public persons together as a couple, which also is a very interesting feature because it shows the intimate collaboration, the intimate scientific collaboration, which happens into an intimate relationship, a husband and wife. And so that, I think it caught the public very much. You know, you have this picture of a husband and wife working on a totally new phenomena that really had triggered a lot of attention by the wider public, so you have all kinds of ingredients. You have the radioactivity itself, but then you have this couple, you have this young woman who well, she's not that young anymore because she studied later, but who all by herself tackles a problem that some others have left on the side. So there's a crystallization of a lot of interesting features that make things kind of pop, you know, in popular culture.

[Federica]: This podcast, Technoculture, has a special connection with Marie Curie for obvious reasons. It may be known to most listeners by now that I am an academic researcher and Marie Curie grantee. That means that my work is funded by one of the Marie Curie Actions, which are European mobility research grants. The fact that I'm sitting in Belgium right now is thanks to Marie Curie, and if I'm having the podcast, it's thanks to Marie Curie. So when I first got the grant two and a half years ago, I felt it was my duty to educate myself more on who she was, why they would choose to name these grants after her and not someone else, and I didn't know much about her except the name and the connection with radioactivity. So I got me some books and I watched some documentaries, and I was very fascinated, of course, by her scientific achievements, the public engagement, and her private life. It made me see her in a completely different light, of course. And when she is brought up as a role model for young researchers, I always think to what extent she is actually relatable. She is portrayed as a model of integrity and dedication, and fair enough. We all want to possess those virtues. But at the same time it's a very different game we play today. The first thing that comes to mind is the pressure to publish as much as possible because you need numbers in your resume and you will be evaluated against those numbers, and that will make you advance your career or not. We have to communicate our research to all sorts of diverse audiences. And she certainly wasn't under this pressure, but of course, how hard she had to fight just to get access to education is something we can't even imagine today. So where I'm going with this is definitely not a list of things that are wrong today and things that were wrong then. It's a question for you, a historian of science. I would like to know more about how the conditions under which we conduct research have changed. We know how it is today. How was it for Marie Curie? She was active a century ago. Has it changed a little bit, or it's a world of difference? And I ask because I want us to understand better how she can be an inspiration and a role model for us, because I'm sure she is. I feel she is, but sometimes I find it hard to translate some of her behaviors and moral standards to today's game.

[Brigitte]: So that's a great question, and when you were talking, I was thinking to myself, 'Maybe Marie Curie wouldn't have survived to the way things are done now.' Well, who knows? But it's a world of difference in many ways. So first, let's say the public face of science, as you mentioned, you know, making a fuss, whatever you do Facebook, what I call advertising of science. When you read the biographies so there are biographies written first by the family or close friends, and then there are biographies written by historians who had access to documents, and then comes also all kinds of, I would say, literary biographies, and we can talk about that later when we talk about the episode of her love affair with Paul Langevin. And in all these biographies, it seems very clear that Marie Curie was very reluctant of all the social rules of engagement, and I think it would have been for her really tough to engage the public with her scientific results in the same way as it's going on now. That's a world of difference, in my opinion. The other thing that's a world of difference too is what is called the big science. So since the second half of the century, there has been a paradigm that there is so much information, so much complex phenomena that are now investigated, that it needs huge team to actually really cope with it. And a big example is like CERN, for instance, but there are other things like Genome Project and so on. And it has been told over and over again that this is the new model of doing science. I don't think it is not only 'I don't think'; I'm sure it is not the only model of doing science. There are still isolated scientists. There are still small-size science going on and producing very interesting material. But this all creates a question of how to attribute credit. And why do I talk about that while we are talking about Marie Curie? Because what got her famous is the credit she got for her work, first with Pierre Curie and then alone, which meant that when she was publishing, she was putting her name. Now, if you are in a big team, you have the team leader who usually already has a name in science because that's how he got the team, and then you have all the docs, postdocs, whatever in the list, and it's very difficult for an individual to trace what is his, what is the team's, in this cluster. And the curious fact about science is that on the one hand, you still have all these narratives of heroes, genius, lonely, having this and that conversation with another genius and building science and on the other hand, the everyday experience of a scientist nowadays is how to deal with who [signs 00:14:17] first, who signs last, what does it mean? How do you evaluate the bibliography of someone if he's never first or never last? And so on. So there is a kind of discrepancy between the discourses, you know, the discourse of what science is now it should be a team effort and a community effort and the role models we are still using, like Marie Curie or others. So I think your question is really [unclear 00:14:49] this point because it really shows that despite saying we are further, we are still with our old fairy tales, in a way.

[Federica]: What about funding and support for research? Do you think that Marie Curie has ever written a project proposal?

[Brigitte]: Oh, definitely. Definitely. So part of the legend of Marie Curie, as I said, was forged quite early. There is this insistent description of her first laboratory space which was indeed more like a garage, I would say, in Paris, but one has to know that at that time, having laboratory space was exceedingly difficult in Paris. There were private laboratories, and there were very, very few institutional laboratories, so the fact that Marie Curie got a place to do her research on radioactivity, which mainly consisted on transforming ores and extracting the elements that were radioactive and that demanded a large space the fact that she was able to have this showed and demonstrated that she had good connections. And the first good connection she had was when she wasn't even doing her PhD. It was with Gabriel Lippmann, who was both industrial chemist, I would say, or interested in consultancy within the chemical industry, and he was also very well connected to the Académie des sciences. So that's also how he put Marie Curie and Pierre Curie in contact. One thing that Gabriel Lippmann asked her to do first was doing research on the quality of metals and things like that, which is, you see, very oriented applied science, but he continued to support her morally and with his connections after she started her PhD. Moreover, to support her PhD, we know that she applied for different fundings, mainly from the mining industry and so on. She was living not with a very rich funding, I mean, that's for sure, but she was a person who knew that if you want to achieve a goal you've set for yourself, you have to give yourself the mean to do it. And I think this was a very important lesson that she learned while she was earning the money to enable her sister to study in Paris, become a medical doctor, and as soon as her sister would be finished, her sister would help her to come to Paris and study the sciences. So it's a She was reluctant to play the social persona, but she was a very clever woman and she knew where to ask and how to ask. That being said, she was also an entrepreneur in her way. It is always mentioned that she didn't take a patent on radium which is true, but she did take patents on how to refine it and she was very much involved in standardisation of older radioactivity and things around the radium. So she was not this very pure and almost impossible to really incorporate scientist that, you know, only things about physical processes and how matter is constructed. She was a very practical woman, too, and I think that's an interesting point also in her legend is that, you know, this garage they worked on was later described as a miserable place and it was hard to think about it as a laboratory. And there started the legend that she started with no means, she was doing everything with nothing, and so on which is not the case, and which is not possible. It's not possible to do science without any means.

[Federica]: One of the things that I find the most inspiring in Marie Curie's early life is the determination that brought her to France, how bad she wanted to pursue higher education. That's something that we can hardly relate to because after high school especially in Europe we mostly go to university by default, and some people do so without really knowing what they want, so they choose something, change. It's touching to read how long, also, it took her to go from her country of origin to France. How old was she in fact when she started her studies there?

[Brigitte]: So she comes out of a family where both father and mother were into teaching at different levels, and on both sides, there are scientists to be found or medical doctors, so it's a very intellectual family she comes from. Her sister, Bronis?awa, became the head of the Institute of Radium in Varsovie, in Warsaw, which means that she was a very able person as well, so there's from the start, there's a love for knowledge, there's a curiosity for science in this family, and there is also the situation of Poland then or, if we can call it Poland, because it is part of the Russian Empire, and they have to speak Russian, they have to learn Russian history, and there is a kind of resistance among the intelligentsia by doing out, you know, in the day what is demanded from the Tsarist regime, and then in the night studying Polish, studying Polish history, and so on. So there's a It's almost like intellectual work is a form of resistance, and I think that being in this atmosphere, she and her siblings learned to have this persistence in these intellectual goals, and she was obviously very, very into knowledge, acquiring knowledge, teaching, sharing right from the start. And the funny part, if I may just give this small anecdote, is that when Ève Curie, who wrote the biography of her mother, she started immediately after her mother was deceased. And Ève Curie was her second daughter, and her first daughter became a very famous scientist herself, but Ève was totally different, and one might think that in a way, it was her way of contributing to the legend of her mother. But anyway, when she is describing all these first years, the fascinating thing is that at several passages, at several instances, she says, 'Curiously, one cannot see at that time, one cannot see the family realize what a genius she is.' And I think this is very interesting about this retrospective illusion about writing someone's life because you know where this person got, and then trying to spot the very moment it started and how this genius was discovered by the family. So I insist about the fact that she was in a family where everyone was committed to intellectual improvement, intellectual work, and I think this persistence is a very important sign of her character and maybe in that way, she is a role model, at least to me. I mean, this is a part of her character that I admire very much because this persistence helped her when it was necessary to overcome the social rebuttal of not playing the game, you know, not having a salon like other wives of scientists, not talking to journalists, even sometimes not accepting prizes and so on, but when it was linked to her goal, she was able to do everything, whatever it needed. When she decided, 'I'm going to set up ambulances with radiological instruments to go on the First World War front to help with all the people who are wounded and to help find where the shrapnels are and so on,' she was able to connect with groups of women, she was able to make political connections. So when her goal was set, her persistence was so strong that she would go out of her usual shy way in social matters. And because of this condition in Poland, and because she sensed, she made this pact with her sister Bronis?awa, so Bronis?awa goes to Paris first, and Marie (at that time, Maria Sk?odowska), arrives in Paris and she is... I mean, she's not 30, but she's almost 24, and as you say, she knows the price of getting a higher education not only because she is a woman but also because of her political circumstances in her own nation. And I think that explains why she took her university curriculum so seriously and she ended up brilliantly. I mean, she was second in physics in '93 and then for her degree in mathematics in '94, she was first. And as you say, this is again a good example and a good role model, is that we take things for granted, and this is sad. This is sad because this is an opportunity given to the young generation to go to university to improve one's own intellectual aspiration, but it should not be taken like just a forced path or something you don't think about, you just do.

[Federica]: Something not only fascinating but powerful that I found in learning more about Marie Curie's life is that the highlights that are normally mentioned (like the Nobel Prizes, or being the first woman to do this, the first woman to do that) were not only complex in the real life but sometimes attached to tragic events, like the true story is more interesting and truly inspiring. For example, if you only know that she was the first woman to get professorship at the Sorbonne etc., etc., you say, 'Okay, okay. She was a genius. Right?' But she only got that because her husband had died, and even then it wasn't obvious that they were going to give it to her, so when she obtained the title, I think it must have been bittersweet for her, and 'bittersweet' doesn't even start to cover it. So if you know the true story, I think that her life becomes the real inspiration, and there is something else I'd like to mention concerning being the first woman to do this or that. I can't help thinking that for one Marie Curie that we know today and that successfully pursued higher education, completed her PhD, and then even had a career in academia, there must have been many other women who were just turned down, who failed or the system failed them. You know what I mean? Even pioneers have predecessors. So how many women were contemporary of Marie Curie and they were just turned down? It's not that You know, she's unique in her success, but it's not that she was the only one trying.

[Brigitte]: So women, women at the university, appeared, I would say, after the 1860, and those women are generally people, women (those are people too), women coming from Eastern Europe. There was a very good window in Russia where women were allowed in universities, and then this window shut down. And the women had a taste of emancipation, if I may say so, and also it was a way to leave a very oppressive society and regime. So you have examples not really here only in chemistry, but you have many examples of other women (like Sofya Kovalevskaya, who's very known) who would go either marrying, you know, to make sure that they had a chaperone, or going alone in group... I mean, alone, two women, alone, and they would get an education. And they were tolerated because they were not from the country, if you see what I mean. So it's a very weird thing that happened is that because there was this pressure of foreign women, slowly mentalities also changed for the French, or Belgian, or Swiss, or German women, but it's very funny that the pressure came from outside, and so she was... I'm not sure she was the only woman. I think So she was the only woman, but what is more interesting, I would say, is that because she was a woman and because the males would go for a career, they would go to topics that were more rewarding or apparently more rewarding, and this is how her choice to study radioactivity was kind of peculiar. Everyone was talking about, but nobody was very sure how to approach the problem experimentally, theoretically, and it wasn't clear that this would be rewarded by a scientific career. And you have the same phenomenon with crystallography, for instance. There's a lot of women at the beginning of the history of crystallography. You also have a lot of women in other spheres like genetics and so on. So it's kind of The general picture is a new population, a minority, can express itself in topics that are very risky, and this is what she does. And the interesting point with Marie is that she chooses this topic, she enlists the help of Pierre Curie, who had devised with his brother Jacques several instruments, and one of them was turned into an instrument to measure radioactivity, so she was able to quantify this. And at one point during her PhD, Pierre is so So he was in a totally different area (crystals and solid-state physics, I would say), but he realizes the potential of what radioactivity can be, the study of radioactivity can be, and he joins her. So she was the one who started it, this scientific study of radioactivity, and when the Nobel Prize is announced well, first in private letters it is announced to Henri Becquerel, who discovered the phenomena and who was at the academy, and it is also announced to Pierre Curie, who had at that time published a little bit with his wife. And he writes back to the Nobel Committee saying, 'Look, I will not accept the nomination if you don't include my wife because she is the one who did it as her PhD thesis. The first paper is published under her name in Académie des sciences, sponsored by Gabriel Lippmann,' whom I mentioned earlier, and this is how she got the credit. And by that, what I want to underline by this story, what I want to underline is that her conditions were really difficult, like for all the other women in the sciences and in the university, and when a minority is faced with any kind of discrimination, the only way for this minority to be recognized and acknowledged is for people from the other side to support them. And in this case, Pierre Curie made the decisive step to say, 'This is not only my work; this is the work of my wife.' And I think this is a very important step, and going back to our discussion about credits and attributing credit, again, those who are in power have the possibility or not to attribute credit correctly. And in this case, this was fundamental. And it was [unclear 00:35:02] fundamental for Pierre Curie, because amazingly enough, he was well known in the scientific community in France. He was well regarded, but not to the point to be seen as a hero, and it's only after he got the Nobel Prize that he was offered a position at La Sorbonne, the exact same position, as you mentioned, that she got after her husband died. So, you know, there's a kind of [chain of 00:35:35] events here. You see that there are circumstances, but then there are also, there are circumstances against Marie Curie, but there are also a lot of circumstances in her favour. I mean, it's kind of dramatic because she had to be a widow to become a professor, but that's how it happened, in a way. She became a professor because she was a widow. Had Pierre lived longer, I am not sure she would have had the same career, and this refers also to this idea of the couple I was referring to before, because they were seen as a unit and the man of the unit was given the course at La Sorbonne, the chair, but the icon of the unit had to be maintained, so the chair was given to Marie Curie, if you see what I mean.

[Federica]: Yes, and she had quite a different experience the second time around with the Nobel Prize. Would you like to tell us a little bit about that, because it relates to the affair you mentioned earlier in this conversation?

[Brigitte]: Yes, so indeed, that was a... I think this is an interesting episode. It is an episode that, in my opinion, can bring Marie back to herself and maybe help us to see how her weaknesses or those were seen as weaknesses how her weaknesses, her faults, her human side can maybe also teach us something as a role model. So in 1911, as you mentioned, she's a widow, and she actually has a love affair with a former student of Pierre Curie, Paul Langevin, and Paul Langevin was not happily married (that was well-known), but the family, the stepfamily of Paul Langevin, starts to do a public campaign on Marie Curie on this, and her affair. So the basic line is that this is this Polish woman who is stealing the husband of a wonderful brave French housewife. And it's very interesting that all the good aspects that crystallised around her first [Nobel Prize 00:38:20] and her first legends are suddenly completely inverted, so to speak, perverted. So instead of being the loving wife and mother of Pierre Curie, she is this widow who doesn't respect the memory of her husband and steals the husband of someone else, and even the radioactivity, which was seen as something amazing and maybe positive for medical reasons, becomes a kind of a sign of witchcraft. And then last, but not least and I would suspect this must have hurt her immensely is the fact that despite her being in France for a long time, having married a French man, having two kids who are French citizens, she is labeled the foreigner. So, you know, all the romantic nice things in the first social public image are just totally changed, and it is a very hurtful period, and it affects her even in her scientific sociability, so to speak, because the Nobel Prize is awarded to her, and the Nobel Committee writes a letter saying, 'I'm not sure under these circumstances, and with the scandal that's going on, that you should come to Stockholm to get your medal.' And the same happens, but not directly, with the Solvay Conference where she is also heading the first Solvay Conference in physics. And here we see the persistence of Marie, which is broken inside, and all the biographies and even documents show that, demonstrate that she's broken inside but she keeps the course. She goes to Stockholm. She goes to Brussels. By the way, in Brussels, she goes and Paul Langevin is also invited. She goes nevertheless, and she does not interact with the journalists, and the newspaper, and the magazines. But what is really interesting too and I think this is also a lesson for scientists that, in a way, whatever credit and ideas you have, you're never alone, you're not alone either in times of turmoil, because whereas she doesn't react and she's not in a state to react and to fight back, a close group of scientists, intellectual historians, around her (they were already befriended for several years) takes the lead into counter-attacking and, so to speak, do damage control. And this is also an interesting aspect of her biographies that she was able to create around herself an environment that was supportive of her aim and goal and also that was supportive of her unwillingness to engage too much in social public activities but would compensate that in times of, in dire times. So it shows a lot of very human aspects and, to me, very endearing aspects of the person that are not always fully acknowledged in the role model. She's most of the time described as someone impassable, with no passion, or, you know, mastering her passions, someone who sacrificed her life. And I remember her granddaughter, Hélène Langevin Yes, by the way, the granddaughter (they were marriage between those friends in the end, so the lineage, Curie and Langevin, is now mixed), but saying, 'My grandmother never sacrificed. She did exactly what she wanted out of her life. She wanted to do science. She doesn't want to be an adulated social public person. She wanted to have a secluded life, and, of course, she worked a lot, but it was her passion. She was passionate about what she was doing.' So this social how can I say screen she would put off does not always give full access to the person Marie Curie, to the real Marie Curie, and it is by learning more about the real Marie Curie that I think we get even more of a I don't know how to say that of a way to lead a good life.

[Federica]: There is a passage in one of her letters that I read and that really stayed with me. And it's a letter that was written precisely during this affair. It was not going well, and she writes that she can't sleep well and that she is feverish and cannot focus on work. And I thought, 'Whoa. Of all the things you can imagine of Marie Curie the legend, Marie Curie the genius, the last is that she cannot focus on work.' And that changed the way I saw my own work. I thought, 'Look, if she fought through these hardships, it means that I too can fight through these hardships that I'm experiencing, and it doesn't mean that I'm going to achieve the same results, but the fact that I have emotions and then I'm human doesn't mean that I cannot do great work.' So you see how knowing the full story, knowing that she too was having a hard time sometimes just like we all do, makes her more relatable and makes her story more powerful. But then I thought 'Knowing these details is making her more relatable and is giving me inspiration, but from a scientific perspective, does it even matter that she fell in love? Does it even matter that we know that she fell in love? What difference does it make? She still got these results, and all that matters, in a way, is the contribution that she gave to the scientific community and to the advancement of knowledge. She's done something useful. It's not that by looking at her life we can derive a conclusion that she could have gotten a third Nobel Prize, but look at what was going on in her life then.' Or, I would say, 'Look at this person's life. She's had it rough. Therefore, she was mediocre' it's not these types of interpretations we want to make. So besides the inspiration, what kind of light can these details shed on the scientific achievement? What is the interest of the historian of science to look into somebody's life?

[Brigitte]: Well, I guess you will have different answers from different historians of science, but there is a consensus that the more you know about the character you're writing on (be it a biography, be it something else) the more you know, the more you are able to perceive the world, to some extent, in the same way as he or she did, and the better, the closer you can get to interpreting documents or events. So I think that, in any case, having a closer relationship with its object of research is a good thing. I mean, of course it has to remain critical, I mean, because historians are not writing hagiography, that's for sure, but there has to be a level of human engagement, at least in my opinion. I think it's something important, and I think it's also something that enriches and provides more levels and more depth in writing the history. And I also believe that this is what the public wants to hear. I think that this is, again, a paradox. We like to be able to put back into just one point a discovery and a big name, you know, like, 'This person invented the Big Bang at that time, and that person did this and that.' But beyond this kind of singular point, we want the whole story. We want the fabric of science. We just don't want dotted lines that we have to connect ourselves. I think we do want to find the human thread into that. So that's my perspective, and as I say, this can be dangerous because you always have to sit back at a distance and think, 'Am I not getting too involved, in a way?' But in this case of Marie Curie, precisely, as you say, this reveals how passionate she was and how her discipline of work which was really impressive was also linked to, was also not only compensating passion but serving passion.

[Federica]: What do you mean by that?

[Brigitte]: Well, I mean that she probably realized early on that if she wanted to get to a goal she had set for herself (which was you know, this is a passion when, you know, you set yourself a goal, usually it's out of passion), she would have to channel herself, channel her passion in a way that it's going to be productive, so to make You can be passionate and like fireworks, but that does produce a big flash and then nothing, and then you have to have a long-term passion, you know, a long-term love affair with science which she definitely had and for that passion to endure and to be fruitful and so on, there is a need for a channeling to use most of the energy of that passion in a productive way.

[Federica]: Getting to know the details of somebody's life brings them down to earth and makes them more relatable. I think it's what we've done with Marie Curie during this conversation, showing that when you take an icon down, it's not necessarily a destructive act. It's not necessarily out of spite for the icon. It's because what you're left with is more useful; it serves you better. I do claim that icons such as Albert Einstein, for example, the most famous scientist of all times, and Stephen Hawking more recently in other domains, Mozart in music, the music genius par excellence they do not serve science or music well. They do not serve the community of people that engages with that art, craft, or science as well as more attainable models. So I would like you to introduce this topic of the heroic creator and of icons in science because we will explore it more extensively in part 2 of this episode. Part 1 was dedicated to Marie Curie on the occasion of her birthday, November the 7th, and Brigitte and I will keep talking through another episode of Technoculture, but could you please, Brigitte, introduce a little bit this concept of the heroic creator and icons or taking icons down?

[Brigitte]: Yes. The thing is that that brings us back to this rhetoric of science, of research, scientific research, that it should be team-like now and it's a communal enterprise, and then the narrative of heroes. And this is the paradox I was talking about earlier, and, of course, in the case of Marie Curie, she is a reluctant icon, but she nevertheless is one, and in the case of Einstein or Stephen Hawking, for instance, you mentioned earlier, I would say that they embraced it to one point. Maybe they understood what they could expand, so to speak, their influence or their impact not only about science, but about other things, but it always goes back, as you say, to the fact that we need models, we need role models, and we need myths to grow, and a figure like Marie Curie, she is a science symbol of some sort. And also, she also is a woman symbol, so she and... I have a problem to say 'she', but, so the symbol Marie Curie, which is not necessarily the same as the historical figure Marie Curie who existed and lived, loved, had problems, so the science symbol Marie Curie is something that completely escapes Marie Curie in the end and also escapes to some extent her descendants. And it is something that it's plastic, since it is like something where the viewer is actually putting everything inside what a science symbol is. I'm sure that if there were studies, serious studies, about all these science symbols like Einstein and Marie Curie, everyone has a different content for what it represents for him or for her, and there is this construction that is really a collective construction, but at the same time everyone has a kind of special connection or a special place. So it's a myth; it's not the real thing.

[Federica]: I guess this was the sign that we should continue this conversation in part two of this episode. Thank you so much, Brigitte, for being with us on Technoculture today. Happy birthday to Marie Curie, born on November the 7th, 1867, and talk to you next time exploring this topic of icons in science.

[Brigitte]: Thank you. Bye-bye.

[Federica]: Thank you for listening to Technoculture. Check out more episodes at technoculture-podcast.com, or visit our Facebook page @technoculturepodcast and our Twitter account, hastag Technoculturepodcast.

Page created: November 2018

Update: November 2019

Update: October 2020

Update: July 2021