From litography to digital imaging: Meaningful enterpreneurship

with Bruno JehleDownload this episode in mp3 (47.53 MB).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

It took me years to understand what Bruno does for a living. Every time I heard a different story, which was completely fascinating on its own, but I couldn't stitch the pieces together. Finally, with this interview, we get to discover Bruno, the man, the lithographer, the enterpreneur, the intellectual, and the good man engaged with socially useful work in India.

Bruno Jehle, founder of bj institute, lives in Aarau, Switzerland and Hyderabad, India. His background is in photo lithography, prepress, information science, internet services and software development in SaaS (Software as a Service). He has more than 30 years experience in building up service companies in Switzerland and development cooperation projects in south India. Bruno is chief expert for higher education on vocational training in the field of Mediamatics in Switzerland, and technical manager of the digitization project at the art museum of Basel.

Beside his economical activities, he is president of "Digitale Allmend", a society promoting and protecting digital commons in Switzerland, and he is an active member in Wikipedia.

In 2015, I was attending a conference on audio preservation in Brussels, when my attention was caught by a voice, speaking from the podium about "quality" and how we need to better understand and re-define this concept. We must stop assuming there is a relation between money and quality, as in: the more money you have, the better job you will do - a relatively popular notion in the field. With his experience in photo litography in Switzerland and with managing projects in India, Bruno understans what it takes to "get the job done", with a great love for detail and a varying amount of resources at hand. I've been fond of him since that day in Brussels four years ago: it's my pleasure to have this caring and talented man on Technoculture.

"Everything in technical sense becomes simpler, and everything in the legal sense becomes more complex."

"Concepts have side effects."

Fig. 1 - Aged glass negative with temple.

Fig. 2 - Palm leave script from the Oriental Institute in Chennai: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palm-leaf_manuscript

Go to interactive wordcloud (you can choose the number of words and see how many times they occur).

Episode transcript

Download full transcript in PDF (150.18 kB).

Host: Federica Bressan [Federica]

Guest: Bruno Jehle [Bruno]

[Federica]: Welcome to a new episode of Technoculture. I'm your host, Federica Bressan, and our guest today is Bruno Jehle. He lives in Switzerland. He has more than 30 years' experience in building up service companies in Switzerland and development cooperation projects in South India. Bruno is chief expert for higher education on vocational training in the field of Mediamatics in Switzerland and technical manager of the digitization project in the art museum of Basel. Welcome, Bruno.

[Bruno]: Hello, Federica.

[Federica]: I'm very happy to have you on the show because since when I met you a few years ago at a conference in Brussels on digitization and preservation of cultural heritage, I have grown fonder and fonder of your activity because not only you're active on so many fronts and internationally (actually, intercontinentalIy), but you always keep, like, attention to people at the core of what you do, even when it involves, well, technology or other fields. I'm especially interested in technology. So to begin with, I would like you to tell us a little bit of what the BJ Institute - which you're founder of; BJ, of course, stands for Bruno Jehle - what does it do? What kind of platform it is?

[Bruno]: Well, BJ Institute I started because my wife told me I should name it that way.

[Federica]: [laughs] Then it should have had her name [from 00:01:43].

[Bruno]: Yeah, no, no, no, she was afraid that I will move away if other people are very eager to take over the activities, as it happened sometimes in my life. So she said, 'Whatever you do, make it in a way that you stand [unclear 00:02:02] person behind the activities, and if it becomes interesting, you know, in an economic way, don't move away. Keep it on track. So the only way to prosecute this is if you make it in your name,' so she told me, 'So call it BJ Institute.' So about the activities: I had, I built a company in Switzerland in the field of media asset management, so we had customers such as Swatch or [FIFA 00:02:34] or other international organizations, companies, and we organized all their media data to be accessible by not more than a browser. I think we have been one of the first companies to use only the browser for media data management such as image databanks and things like that. So after a while, I felt my contribution to the company, the time of, the value of my contribution to the company, even being a founder, may be over because now it's needed, for the demand of the customers and for the prospects of the team, they have to scale up, so they want to become international. They want to have customers in the United States, in European Union, all over the world, and so you have to rework all the process. You have to build up a marketing department and things like that. So, and...

[Federica]: Yeah, being successful is work, huh?

[Bruno]: Hard work, really hard work. So I may be more of a pioneer. I can do the things until they really work, but when it comes to the moment when you have to scale it, I felt that I have a few weaknesses. I find it very difficult to motivate myself on the needed level to commercialize the thing, so I thought going to these fields where you really have the heart, so it's more in encouraging young people to learn, to make experience, to build trust to build on their own experience rather than to run behind some theoretical concepts.

[Federica]: Well, I know that you have started several times in your life...

[Bruno]: Yes.

[Federica]: ... as a pioneer something from scratch, and it normally became successful. It's very interesting, this dynamic.

[Bruno]: No. No, no, no. That may be the impression. I think you have to do many tries, and at least people see only what is successful. They don't see that many times you fail.

[Federica]: Aha. That's deep. Well, let us take a step back to before the BJ Institute was founded. There is something fascinating about your profession that one doesn't learn right away, that it's something that I found very fascinating, and that is that your initial training was in photolithography.

[Bruno]: Correct.

[Federica]: I find it fascinating because it's a profession for which you have not received like two months' training; it was a part of your life, and it's a full profession - however, one that evolved through the years that was heavily impacted by the advent of digital technologies.

[Bruno]: Yeah. Yeah.

[Federica]: So the way one performs that profession is not the same at all today. We know that you have successfully transitioned to, if we want, the digital world, but how has the process been? How has it been for you to receive that kind of training and then see what you knew in desperate need to be updated all the time?

[Bruno]: Yeah, that's an interesting point indeed. When I was 16, I started an apprentice as a photo lithographer in a small little graphic company, and they have been specialized in high-quality reproduction of old cultural values. For example, paintings in temples in Burma and Thailand, Buddhistic and Hinduistic images and reproduction, highest possible quality of historic books. So I had, from the very beginning, I was in contact with this type of preservation of values from past culture, so somehow. But I made it to... The profession of lithographers is equal to typographers. These are very proud people, especially the Swiss lithographers with the cartography. I mean, making the maps and things like that. And they have been very proud and they wanted to earn good money and they said, 'The way we can do that is, we have to deliver the best quality worldwide. Then automatically, our work will have a value, and we want to have a share of this value.' So they understood that it's a small group and they cannot work each one against the other, but they have to support the others in the aim to get the best possible knowledge about everything concerning the profession. So they have been bright people, and, you know, there are even some rituals when they accept a young professional to be a lithographer. So this is building identity.

[Federica]: Right.

[Bruno]: So even with 20, you know, they push you under water, and when you come up, you're one of them.

[Federica]: Wow, like a society.

[Bruno]: Like a society, indeed. So I learned from 16 to 20 that doing something is not only earning money with something; it's taking responsibility for the knowledge of the past in that field and guiding young people to take it somehow serious, that it is building identity what you are doing. So technological changes, photolithographer, means being a lithographer with photographic material. Previously, there was the stone lithographers, so they had to paint on a lithographic stone this was the first real photographic reproduction technology. You could print maybe 1,000, maybe 2,000 copies if you do everything right, and then your painting [unclear 00:08:55] all the stone will be washed away by the physical use while printed. And so everything evolves. So instead of painting, you used photographic material, so it was not very surprising that of photography, new technology comes up. What was interesting to me was the experience by this way of [social 00:09:23] organization of the trade that, the pride, what you do you do it the right way and you try to understand your social responsibility. I mean, if we look today in the way we do our job, you have so many aspects. You have an economical aspect, if you earn your money for yourself, maybe for your family, but then you have a certain responsibility for the experience which is in that profession, and you have a certain responsibility for ecological aspects. So if you use everything only to a commercial, to a higher and higher type of doing your job, then you're very poor if you compared it to an understanding that in a society with so many specialized activities, you are a specialist in one of the specific fields, and you have certain responsibility as well as a social responsibility. You have an ecological and economic responsibility, but that's a wide field of understanding your trade. We all are specialised somehow, but can we take responsibility for what we're doing? Usually not. So I was interested in, so I built my own company in that field to actively participate in the migration to the digital age of this traditional trade.

[Federica]: I like how we approach this concept of responsibility, and I wonder if it is possible that the reduced responsibility that we see in workers today, it seems so - generalizing - as opposed to in the past, may be laid at the feet of something that's positive, and that is optimization. Do you think that it is possible to have a positive narrative around this, and that is, we are part of larger complex processes, and for them to work smoothly, we have to make each step less complex? So each individual person who is part of the larger scheme needs to take less decisions, and this under the name of optimization, which I understand is a tricky word because it can be seen as something positive as it is, but with this negative possible meaning of maximizing productivity for its own sake, maximizing profit, so to make the process better not like because the work calls for it or because it will make the people feel better, but because of maximizing profit. However, let's keep the positive meaning of 'optimization'. Do you think that it is possible that responsibility has been lifted off most workers under the name of this, the process of optimization?

[Bruno]: No. I don't think, really. I think if you look at the culture and the society as a whole, there is the same responsibility for everything. The question is where or what decision's taken and where is your part of the same? So if you make a company and if you are chairman of a company, obviously, you have clearly responsibilities, but if you are in training and education, obviously you have some responsibilities. So I think it's a type of illusion that we have less possibilities to, in a way, to define the way we understand and we act as professionals in our specific field. I think it's a question of whether we are aware of that and how we use it, and often, I feel those people who understand this, they are somehow qualified to take responsibilities for others, but if you ignore it, obviously you're not prepared to take responsibilities for processes and for other people. Maybe there is an interesting historic point. When I was in my apprentice, we reproduced books, ancient books, of some value. One of the books was the book binders' identity or the book binders' law, you can say. Interestingly... I mean, it was about 1680 or something. So it was not just the state law, what was relevant for the professionals. The state law pointed out you shouldn't kill, you shouldn't steal, you have to do this and that, but it is forbidden to act like this. But this was same for everyone, but bookbinders had their own moral. They had their own, 'You shouldn't go for prostitutes,' for example, is written there and things like that. So it was a law that made you to be a bookbinder, [a moral 00:15:07] to act as a bookbinder, and that was surprising to me, with 18 years when I read that thing, 'How is it possible?' But historically, to work in a trade means to have a certain responsibility for the trade, and that responsibility was not connected purely to economic decisions.

[Federica]: Wow. This really sounds like something that comes from a past long gone.

[Bruno]: Yes, but maybe this way of looking at the things could be relevant in future if we think of artificial intelligence and robots and what makes us, as humans, different to artificial steered robots. It's maybe coming back in another way. I think the [longer 00:15:59] the more I think the social organization of professionals in their trades becomes more important as more and more work can be done by robots and can be automatically steered, so I wouldn't say that this is just something from the past. It's maybe a concept which is interesting for the future as well.

[Federica]: Speaking of the future, Technoculture, this podcast, is about technology, but it's also about humans, and what you just said triggered this association in my mind and that is to the fast pace at which technology seems to be advancing. It's part of what I like to call [technorhetoric 00:16:52] and that is some statements we take for granted (like 'technology advances fast'), and a consequence of that is that we struggle to keep up, and in the job market for example, the mantra is, 'Just keep learning, lifelong learning,' which in itself doesn't sound bad - actually, it's a good thing - but it's under this sort of anxiety, a sort of pressure to keep moving forward, forward because technology advances, and it's like we struggle to keep up. And I take issue with that rhetoric because I think that who makes technology? Humans do. And why? To make our lives easier. So it seems to me that your profession is an interesting example of a group of people that saw their craft change in the methods and instruments beyond their will. It just, what it was. You had to drop old habits and learn new skills, but because as a group you had a tradition, you had a culture if I may say, you had a code of honor, that helped to maintain the people on top of the changes. Like, 'We master the changes. We don't chase them.' Am I getting a right impression from the group of professionals, of lithographers, bookbinders?

[Bruno]: Yeah. Yeah. I think it is because of the pride of these people, and they understood that they are real professionals to publish or to multiply visual content. So the first way to publish pictures in high quality was, in many numbers, to multiply, was lithography. So you'll find old lithographic pictures in highest quality, they used maybe 10 stones, 10 colours, and it was not just a standardized process, so these people have been really artists. But what they... Maybe I speak about, like old lithographers [thinks 00:19:13] that way, they are not existing anymore, but I can only speak individually about what I learned and why it was for myself important to have that roots in tradition. I think what we are doing is less defined by technology. It's defined by our understanding of what we are doing, so lithographers have been specialists to publish visual content. Now, what I learned by digitization, especially in the last few years, the problem moved from a purely technical problem to a legal problem, because intellectual property. So being an expert in publishing visual content, we have to know about even the legal aspects. Otherwise, we are not really specialists up to date to act as specialists with technical and legal and all obstacles when you want to publish visual content. So everything is in transformation and I think that, as a general tendency, we can say everything's, 'everything' in technical sense, becomes easier and everything in legal aspects becomes more complex.

[Federica]: Mm-hmm, so the legal aspects and implications of your profession were not as problematic as they are today in the digital world, so to speak.

[Bruno]: No, imagine if you have to draw on a stone for every color you print. So if you print, for example, in ten colors a map, you need ten stones in the original size of the map, and you have to paint reverse, so side wrong. You cannot even read it if you are not a professional. And it must have register. Can you imagine? So the technical complexity was the protection even of the content, because no one else could do it unless he controls the tools and the machines. So the weight of the lithographic stones for one map was maybe two, hundred kgs, maybe 500 kgs. Just weigh what you have today in bits and bytes on the hard disk, because you had use stones to paint on for every color in the original size, and these stones have to be stable even under pressure when you put the color on and put the paper in contact to the color on your drawing, on the stone. So that was a protection for the trade, the technical complexity and the skills, obviously, the skills you need to paint on a stone and to control all the chemical process to bring it to the paper. What's the protection? Now, all this protection is gone away. You have, in every smartphone, you have a 12-megapixel or 20-megapixel camera, and if it's a bad one you have quite good results on it, so everything became very handy. At the same time, the legal question - are you allowed to do so? Are you allowed to publish? Are you allowed to take a picture from the same? Are you allowed to publish the same? - becomes more and more complex.

[Federica]: So reflecting on these things is how you got involved with copyright issues.

[Bruno]: Yeah. The first time I heard about it, and I couldn't believe it, was with the Chaos Computer Congress in Hamburg. It was mid-'90s, and I had the opportunity to hear Wau Holland. He was able to speak just one and a half hour without break about this issue, about this topic, and it was very fascinating for me because he explained that when in the former Communistic DDR they had the First May celebration and they sung the Internationale on the roads, they had to pay royalty to the owner of the intellectual property. So that was amazing for me.

[Federica]: Wow.

[Bruno]: I couldn't believe it, but it is a fact.

[Federica]: Excuse me, is intellectual property, IP, the same thing as copyright?

[Bruno]: Yeah, IP's a little bit more than just copyright. So patents for example are an issue of intellectual property, while copyright is limited to copy something what is published.

[Federica]: Okay, so intellectual property means that I've had an idea and the idea is protected, but I can have an idea and you can copyright it.

[Bruno]: Ideas on its own, I understand, are not protected, but if there is a technical...

[Federica]: A product.

[Bruno]: If there is, technical aspects of how you transform your idea into a technical solution, for example, it can be a patent, but patent, you have to register and the patent is limited in time, while the copyright is, as per the law as we have it in Switzerland, Germany, and I think all of Europe, is by the creative content is protected for every person who is creative. I mean, a very strange and idealistic concept. The only thing is, it's not working in reality. That may be a disadvantage of that concept.

[Federica]: You know, in principle, it seems something that makes complete sense. It makes sense to want to protect the product of somebody's intellect so that other people will not wildly capitalize on it. It makes sense. So what is it that doesn't work in reality? What's wrong about it?

[Bruno]: Well, like all the intellectual property, it's fostering the development towards monopolies. Because it's not wrong that the creative person has got a right on his creative content, but the problem is, this right to publish usually is handed over to publishing houses, or to collectors, or to companies like image banks who buy it and who sell it with big organizations. So, as I told, the concept behind this is very idealistic and nice idea, but the question is, how does it show up in reality? And now, all intellectual property is fostering the monopolization in companies with big capital, and long after the death of the creative person. For example, now you have 70 years after the artist dies, still the copyright is active. And gradually, they are prolonging that duration of protection, so no one can say that you are interested and it's supporting your creativity of 69 years after you died. That's all the question of who gets the profit of the monopole. That's the main question. The main problem, is these are all monopole rights, and to some extent, that's fine. Another problem is, it's not just if you write a book of 700 pages, and for sure, it should be protected, I agree. If you make an illustration, a scientific illustration, or an art illustration, your rights should be protected to earn money with the same. That's not the issue. The issue is that not the Werk, as we say in German, artwork as a whole is protected. If you write a composition in music, the problem is not that the whole work of your composition is protected, but every element of it which has a certain level of creativity within is protected, and that leads to a situation where I remember two examples. One was a YouTuber who put a video on YouTube collecting wild salad on a field, and he filmed what you can eat and how you can use it, and in the background there was birds singing. Now, as he was... I don't know, it was maybe 15 minutes or something, so there was a lot of patterns of birds' songs in the background, and the video was blocked on YouTube because the patterns... You know, these robots for avoid misuse of intellectual property, they have to concentrate to formulas. So it's not the music as a whole; it's elements, short snippets of music. It's like your fingerprint. It's not as an image stored. It's as a code it's stored, compressed as a code.

[Federica]: But what was with the birds?

[Bruno]: Yeah, so the birds created some patterns, acoustic patterns, which are similar, if you cut it in small pieces, to any type of composition. So this happens not once, this happens many times. And only those people who are aware of the problem with the intellectual property and the patterns understand that in future you have to be programmer and lawyer to be creative, because the patterns you create may be already existing. Imagine we have a copyright law in Europe that all of your creative content is protected by constitution, and this, 70 years after you die. Imagine how much creative content is protected and monopolized. What was made initially to protect mainly the publishing houses and not the creative people, I think the whole thing started with editor of Shakespeare, because the creative people usually, they think of what is there, 'I can create something new,' but the editors, the publishing houses, they are [100%] relying on monopole right to capitalize the creative content of artists. So that all evolved in a few hundred years, in two, three hundred years. An interesting aspect is, the first copyright was, as per my knowledge, in England with the publishing house of Shakespeare, and so they tried, of course, to optimize the income by the monopole they had I think for, I don't know whether it was ten years, something like ten years or five years, and then it should fall into the public property, even the ideas, the concept, the text. In Germany, this concept was not there. So that leads to a situation where in England the books have become very nice piece of artwork with gold patterns on the cover and very nicely done, while in Germany, there was such a competition from the papermaking to the bookbinding to the printing process, even to the sales places for books, so that created a situation that the competition made the German book printing machine builders far more competitive than the British one, than the English one. So that's why today with Heidelberger [unclear 00:32:25] if you look at what is existing in the field of printing, you'll find everywhere German companies as number one, because the competition created the situation where they had to be better, and in Germany, Germany became then the land of the writers and the thinkers because everyone had access. It was not so much of an economic problem, because if you work as a kitchen maid, you cannot buy a book with a golden cover, but maybe you have been able to get it on very cheap paper without even binding a novel and lend it to someone else and things like that. So it was more prominent in the public, and the competition among writers, the competition among machine builders, the competition among paper makers became very intense, and obviously, the quality of the products improved in this process. So the concepts have side effects which are out of focus of those who implement new laws, and I think now in the digital age, we are in a situation where the whole thing becomes more and more complex, and side effects may oversteering the wanted effects while implementing.

[Federica]: So concepts have side effects. That's interesting, and indeed I had never thought about it. Did I just hear you say that the introduction of copyright in England, as opposed to in Germany, actually slowed down an entire sector of human activity? Is this what you actually just said? It's a big statement.

[Bruno]: Yes. Yes. That's proven. That's proven. For example, we can have a look in another field. You see the chemical industry in Basel is maybe well-known with all these medicine producers in Basel and the chemical products, producers, such as [Sandoz 00:34:40] and Ciba-Geigy historically, and Hoffman-La Roche and things like that. So how it was possible that Basel became a hot spot? Interestingly, now Switzerland is trying to get the best possible protection for intellectual property on patents, for example. We would have a free trade agreement with India if not the chemical and the medical industry, the pharmaceutical industry, from Basel wants to prosecute their intellectual property. Now, the whole story began because Basel is on the river of Rhine, and the river of Rhine is connecting even for heavy loads a good part of northern Europe from Switzerland, so the Basel industry had their chance when there was a patent law in France and in Germany, but not in Switzerland. So they copied old protected products and have been able to sell it to French and Germany. So when they became strong and when they became leading companies, they themselves want to protect what was at the very initial stage the chance for them even to get experience, to get into the market, to build the infrastructure. So I think that is the overall image. When you are no one and when you try to get your chance, intellectual property is against you, and when you are leading and when you try to extend the use of your monopole position, you try to extend always of intellectual property, whether you're an artist or a chemical producer, whether you're a pharmaceutical, or take any field and you will see the same picture. So today, it's a protection of Western states against Eastern upcoming states such as India.

[Federica]: You just mentioned India, and we'll go there, virtually go there, we'll talk about that in a little while, because you have some activities going on there, but let's stay in Basel for the moment. Let's talk about the museum of art. You have collaborated with this museum. What did they need you for? What kind of competences you brought to the table, and what was the collaboration about?

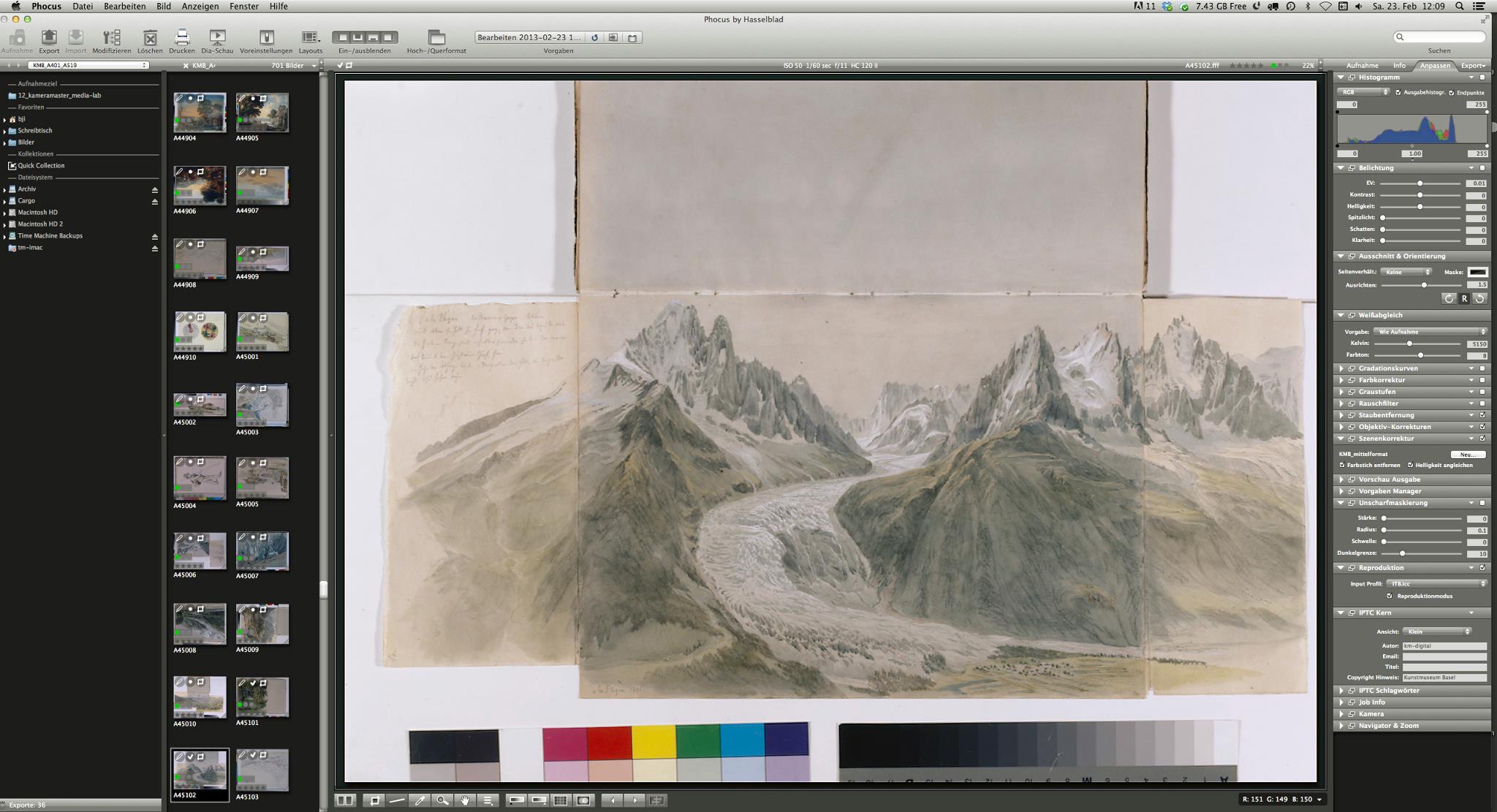

[Bruno]: Yeah. I have been asked by the art museum in Basel of what type of concept the museum could have in the digital age, because they saw that they have different departments, and in all departments, there is a fast development with many new upcoming machines, processes, and it is difficult for management to steer the whole development. So they had a lot of software sellers, hardware sellers. Everyone is always greedy to get the latest technology, to be among the first who use a certain technology, whether it's 3D imaging or whether it's - take anything in future, there will be new technology. So obviously, everyone is always very greedy to have the latest gadgets and the latest toys, to say it like that. But if you have a house of 450 years' experience in protecting print art, the question is maybe less whether you're two year earlier or later to implement technology. The question is maybe more how we get stable conditions to do so and how we can steer from the management, how we can steer the policy of a house into digital process. So they saw that their departments, and they have different museums, they have restoration, they have exhibition, they make a lot of exhibition, they published books, they have library archives, so in all the departments, there is a fast change, and the management was interested in steering or in understanding what are the possibilities to steer that process in meaningful sense. So they heard about me, interestingly, by my engagement in India in the social field, and I was publishing books with the, or making lithographic works for the director in his previous job, so he knows my way of working, and he had some confidence in me in a way, in the method, of how to work towards quality. So he invited me and asked me whether I would present my view, and it was an honor and a pleasure to me, and I came up with a concept that you should steer the whole thing, and you should... The question is - there are many questions, but two of the main questions, what do we digitize in what form and how we preserve it, and the other question is, how can we avoid and [want] material? Because, see, today you have in every smartphone a camera, and soon it will have 4K camera in every mobile smartphone. Can you imagine how much data will be created? Can you imagine how much [unclear 00:40:40] will be there, and can you imagine how in future you want to divide relevant from irrelevant material? So we... The concept I made was built on the experience I have been working with the company of Swatch and of other international marketing companies that it's needed to have clear categories of digital content. For example, you can see a watch from the front side or from the side and from the back side. You can have, you can picturize a watch with bracelet, you know, with a round bracelet, so as, if you wear it on the arm, for example. So you can say, you can figure out there few perspectives of how you can visualize material, so the very same is in the art. There is a picture taken of an oil painting, maybe, from the front side, from the backside, there may be detailed images, there are historic images, but if they are historic images, the question is, is it from the front side, is it from the back side, is it with frame, is it without frame? So if you analyze the whole thing, you come to a certain category of what is meaningful to have of all your artwork in documentation, and there's the timeline is always moving. So the oldest images or maybe [100] photographic images are maybe 100 year old, and maybe in 50 years, you will make again a systematic documentation of the same, but you will make it in 3D and whatever. So we made something we called media standards. There are so many standards, and every software developer will most probably every year or every two year come out with a new software version, and the new software version will have a new data format, will have a new structure of data. The file name may be the same. Have a look at, for example, PDF. The evolution of the format of PDF from the very first to what we have today, PDF only means container. You don't know what is in that container. You can have sound, you can have video in the PDF. You can have, I don't know, in future maybe three-dimensional information, maybe even today. So we should be clear that data formats are like containers, but the structure of the content used to be the business of the software developers and of the strategy of software companies. So usually, they will come out now and then with a new version, and everyone who is not able to read the new data format have to upgrade his software, and you have to pay for. Now you have software-as-a-service, you cannot even buy the software; you have to get it from the cloud and pay monthly. So imagine what that means. You lose control of all your content, and if you are a museum with 450 years, art museum in Basel is one of the oldest, maybe the oldest public museum of the world, so they have been able to control the content of 450 years, but now in the digital age, they are not able to steer the software developers and the licenses, and they don't know what they have on the server. So that was the main question, and the answer is very clear. You have to define what you need, and you have to avoid what you don't need, and you have to make priorities, and you have to digitize all the relevant content in the same way that in five year when new data formats come up, you can migrate to the new formats. So we made a structure, and we started to train the photographers at workshops with all the departments. It was very interesting. It took us half a year to figure out what will be the file name, how should be the file name, because usually we say, 'Oh, that's not a problem,' but if you think in a house with more than 400 years' experience, you will have registration numbers and a lot of different number systems, and old houses, often they integrate other collections, and they have no key to identify a work of art. So the main question is, what is the machine-readable way we can identify an artwork, and how can we structurize the digital documentation of the same, no matter whether it was done 100 year ago, or it will be done in 50 years from now in future so the structure we built was the same? And so things like that, we did. So we call it media standard. It's not that we make new standards. The standards are like a jungle standards can do a lot of good for you, but standards can be a terrible headache for you because there are so many standards, but we try to keep it simple and spoke to many people, for example the scientific photographic department of the art museum Basel, which is called today digital humanities, and try to make it as simple as possible that everyone understands the need of having a controlled eco-collection of material, and we said there will be a few lighthouse projects, you know, every museum has got something all the world wants, and you want to expose it in the best possible way, but if you would take that standard to document all your 1 million objects, for sure you will fail. So the question is, what can serve, say, 99 or 99.9 percent of the cases they need of the public in documentation if you look at it today? And this will be the standard.

[Federica]: Something I like very much of what you're saying that I'm reading between the lines is that even if the big change is motivated, driven by technology, the correct response to it - and your approach in this case - is that of defining what we need very clearly, having clear ideas, clear concepts, because there is a history to be respected. It's not a matter of letting the tech fever get the best of us and always jump on the latest train, but actually respect the history and the tradition of the institution, in this case, that is going through the transition. It's a centuries-long history. The content has always been there. The mission of the institution is that of preserving it and giving access to it. Digital technology can dramatically help that and increase the access, the circulation of the materials, but how do we respect the material? So I appreciate the conceptual clarity very much, and it, again, gives me the impression that you keep being on top of the situation. You're in command. You don't let this tech fever get the upper hand. This collaboration, though, did not just stop with like a consultancy, but was concretized with you mentioned workflows, but also a software tool for the management of this digital data. You showed me that interface, that tool through which several things could be done, and I was very impressed by the resolution of the images, and also precisely the number of images taken for each work of art also across time, precisely in five or ten years' time, we can make a better-resolution image, and we will, or the work of art will be restored, and we will also take another picture and not delete the previous, so now you create a history of digital images of a work. Was that like a backend thing for people who worked at the museum, or our audience could, for example, go online and see it?

[Bruno]: It's behind the scenes. It's a tool for managing all the digital content, but it's hidden from the public, but you can see, if you go to art, Kunstmuseum Basel, of the art museum Basel, and you can see the online collection, and I'm very happy that now you can download even in highest resolution the artwork when they are public domain, when the copyright is over.

[Federica]: Right.

[Bruno]: You can have the highest resolution of the pictures. They don't... They understand it as a service to the public, and I'm very happy about it. I think it's the right concept.

[Federica]: Is this something you had to discuss with them, like were are you on the same page to begin with, or did you have to have a little persuasion...

[Bruno]: Oh, yeah.

[Federica]: ... to make them open up, so to speak, these high-resolution images? Because there is this concept that if you deliver digital content online as an archive, as a museum, then people will not come to you anymore, so the content loses value, so to speak.

[Bruno]: Yeah, that's the fear everyone has. I used to answer like this. See, everyone knows the well-known Swiss mountain Matterhorn, and now if the people from Zermatt, which is the town near the Matterhorn, the mountain, would be afraid they're taking photos of that mountain and spreading that photo, people would say, 'Oh, we saw the mountain. We don't have to go there,' but the opposite is right. They want to have their feelings standing in front of that mountain or standing in front of the painting Mona Lisa or whatever, but that needs at least an awareness of the importance of this type of artwork if we look at the museum. So if you don't make it public, you will lose ground in public space in the recognization. Others will take your place. So the question is maybe more, what are your individual feelings standing in front of something than whether you saw it or not? I mean, we have art books [unclear 00:51:56]. Do you think anyone didn't go to a museum because of an art book? I mean, that's simple nonsense, sorry to say, but it's the atmosphere. It's the now, here, moment.

[Federica]: We talked about this exact same concept with Harry Verwayen, who was my guest on episode number nine of this podcast on Europeana Foundation. We said how everybody knows the Mona Lisa but people keep going to the Louvre to visit it.

[Bruno]: Of course, because they know it and they want to know, 'What is my feeling if I stand in front of it?' Same with a mountain or same with a landscape. First, you have to know, and then you get curious, 'What will be my experience, what will be my feeling when I'm there?' So I think that comes back to us something we talked in the very beginning. We should be aware that our experience will be more and more important in future, and taking the risk to make experience, making mistakes becomes important, learning from making mistakes. The only thing what will have no value at all, and you can't afford to do so, is making mistakes and hiding them, because then you don't get anything out of it. So whether it's a positive or a negative, it's all about your experience. That is different, that makes us different to artificial intelligence, to robots, the sum of our experiences, and I think, I work often with young people, that's what they love, because they can make their experience, but when they have to pass tests, if they make a mistake, they are out if you. If we take, for example, India, I don't know how many people commit suicide because they couldn't pass the exams, they [unclear 00:53:58] bad results in exams, so that future, they feel, is gone. So we have a high rate of suicides of children or young adults who pass exams not in the way they expected, so they think, 'Oh, my life is gone, and I cannot tell this to my parents, and they invested so much, they invested all their money in my education, and now I failed,' so can you imagine? But this way, I think if we look back, the way of our education system is the ideal for the Industrial Age. We wanted to have an operating system; this was the basic education. Then you packed on it a type of program that was your vocational training or your specialized university studies, but all of this, what you can repeat, what you can memorize and recall in all these fields. Computers and the artificial intelligence will be far faster, better, and cheaper than humans. So the concept of education from the past and the way of selecting the elite was made to have to minimize the error rate, and all these concepts, I think, we have to put in question. I think art and social competency, ability to solve problems, ability to handle with mistakes and to get at least an experience out of mistakes is relevant for the future, that are aspects of importance.

[Federica]: You have mentioned India a couple of times during this interview, and I also mentioned that you have some ongoing collaborations over there. I know that you often travel there with your wife, and I would like you to bring us along. Let's go to India for a couple of minutes to hear, what's the nature of the work that you do there? I'm interested in the big picture because we all seem to be moving, right, to this alleged digital future, and I think that it really matters how resources are distributed in the world and how countries and continents are doing today, because this is a gap that will keep widening, so I think it's commendable work that you do in bringing resources and actually helping to organize some work, either in cultural heritage or education and vocational training. So what do you exactly do in India, and, of course, with whom? Who is your Indian counterpart?

[Bruno]: Yeah, we have two trusts in India we built between more than 30 years ago. One is called Rural India Self Development Trust, and the other one is called the People's Clinic Trust. What we are doing, I think the name points out what we are doing, Rural India Self Development Trust. So my part is only to support it. All work is done by Indian people, and some of them I know since more than 30 years. So we share the aim to upgrade the ability of the rural people, the rural poor, to make better use of their resources, and their resources, it starts with the health. When we started in the early '80s, a lot of anemia, a lot of health problems was the problem of these people. They couldn't use their intellectual abilities, they couldn't use their natural resources because simply they have been in an agony and near death sometimes. So they had no access to vitamins, they had a very unbalanced food, and they didn't know about it. And so next step is education. When your health is fine, it's important that you have a sound education, that you can understand, that you can read and write, that they can use technologies in farming which is not destroying the land, and creating a value. So the very basic thing, it starts.

[Federica]: Wait, what is the first step of this process?

[Bruno]: Yes.

[Federica]: Because we are talking about the same man. It feels like two different lives. I mean, it's the '80s and then it's the '90s and we are in Switzerland, we see you as an entrepreneur, you received training as a lithographer and you develop software, and you do this kind of thing. How do we jump to India, being aware that there is lack of vitamins, and that when your health is good then you need education? How did you become these two men in one lifetime?

[Bruno]: Oh, that is a story I [unclear 00:59:04]

[Federica]: Can you make it short? [laughs]

[Bruno]: Yeah. I try to make it very short. See, I was aware as a young Swiss that I'm part of a very privileged society, like maybe only half a percent of the world's population. We had every possibilities. It was in the '70s, in the early '80s, and I understood the privileges I'm having will be very rare, so will it make me happy to even grab more privileges, or will it make me happy by the end of my life when I share some experience, some possibilities, some privileges with other people who have not that chance like I have? And I came to a conclusion that I'm somehow a social being who was only happy when sharing with others knowledge and experience. So I decided to engage myself in India. At the same time, I made the observation that when I engage myself for the future of our society - and that's the disadvantage of rich communities or of rich countries: They mistrust everyone because they reach the type of peak and they think, 'Everything we are doing, we always have the chance to lose, so mistrust becomes more important, fear and mistrust.' So this is not exactly what you're looking for, being a young man in Switzerland. So I, and when I... One day I was living in a community, we have been all vegetarians, and one day we realized police was controlling our house without announcement and without telling us, so in future we had to lock our house not because of thieves, but because of the police, and the mistrust of the society and what neighbors are talking and things like that. So that was an important moment when I realized, 'Ah, it seems to be normal, then when you reach, you mistrust,' and then the possibility to do something for your own society is very limited because every change will be a risk for your wealth or for your position. So then I, by accident - it will take too long to tell the story - I realized that in India, it's different. Change means hope, means chance, while here in the wealthy countries, change means risk. So I felt it's rather my way to stand with those people who want to bring a change and have a hope for the same. So I learned about the word 'nation-building.' Well, you cannot say 'nation-building' in Europe; it's like a bad joke. But in India in this year's, nation-building was something, was a mindset to do something for the good of the public. So I felt I will do my part if my friends in India do their part, and still they are my friends, we did the same. I did my part, I did their part, and as I'm a Swiss, I don't have to show in India how to work. They know how to work, but they must have the chance to do something meaningful, and they must have an environment that they can make a mistake and they are not just out because they make a mistake. So whether it's in trade or it's a farmer who tries a new kind of fruit trees, we wanted to bring opportunities to develop their resources while taking some risks, in many ways.

[Federica]: How many kids have entered these programs so far? Do you have some figures, just to give us an idea of the extent of your network in India, and what's the size of these initiatives? Like it's not small scale, is it? It has some impact.

[Bruno]: I cannot say. We have a school with 1,300 students, English-medium. We have a hospital with about 50,000 treatments a year. We have leprosy control in an area of five million. We have TB control. And that's going on since, gradually it was growing, now it's rather decreasing a little bit because the government is taking over some of the programs. We have to train the government hospitals in that very specific field. We cannot say. It must be in hundred thousands.

[Federica]: Speaking of education, what skills are transferred to these kids to grant them a future, at least in the rural areas of India where you work? I ask that because, again, the mantra in the Western world is that in order to be employable, you need to have digital skills.

[Bruno]: Yeah.

[Federica]: And coding is, I would say, in fashion. It's, of course, useful. I do code myself, but there are more and more courses for women, courses for kids from 14 to 18 years of age in schools. There is this kind of literacy that is required and therefore, fortunately, offered. What kind of profile does a young person have in India to be employable? What's a useful education?

[Bruno]: Well, see, it's like this. The Rural India South Development Trust has got his own track of development, and that development was, as I told, from securing health to upgrading ... You know, that's only one spot in India. India is so huge, with 1,200 million people. Imagine, that's nothing, what we're doing. It's just on a spot in an area, one small contribution. That's so big, you cannot imagine, and the need is so high that whatever you do, it's near nothing. But it can be a sample, and it can change by the experience these people do or by the chance they get with their health, with their education, in the long run. In this area, it will have an impact. Now, we have to see on one side, we have this institution, Rural India Self Development Trust, which was growing for more than 30 years, and now we think, how can we continue? And if we think of how we can continue, India then was really different to what we see in India today, mainly in the big cities. The big cities are booming, and more and more people leave the rural areas to live in the big cities, and they have pollution of air, they have problems with water, traffic [mess 01:06:25], everything, but worse you can imagine here in Europe. So our aim is to upgrade still the life conditions in rural areas, and energy is one of the keys. Communications, energy, education is one of the keys. Now, our observation is that the structures, the more rural the area is, the more hierarchical the structures are, and now the Indian government understands it needs a major change. It needs a change because India cannot compete in the industry production with China, and India finds it difficult to compete with Japan and with the West because the output of the industry is not on the quality level, like we're competitioners. So the domestic market works very well, but that's limited, and as I observe, India wants to move away from the agricultural, being an agricultural society, to be one of the leading nations in technology, industry, in software, in everything. So that's the whole complex, but when I observe is that the rural areas are not really supported, so if you want to make a career in future, you have to go to the big cities and try to make the career there. Being a Swiss, we know that you have the chance even in small places if the infrastructure, the educational system, is developed, as it's here in Switzerland, so it can be even an obstacle if you are in a too big city, because it carries you away from concentrating on delivering quality.

[Federica]: Is there a way in which our listeners can contribute to these initiatives?

[Bruno]: Yes, yeah. So of course we always need money, but we need brains. We need engaged people to share and support our ideas. So one of the possibilities can be to visit the place and contribute maybe with language courses or with training, with [giving 01:08:40] school, because ours is a rural school, even though we have the best results in that district of five million people. It's important to exchange with the West, and it's important to encourage those people who do a brilliant job there, and now coming to BJ Institute, we are rather of a think-tank that we have to think what we have to do that the next generation, this institution stands strong for the next generation. There is a shift away from a more charitable project to a technology-driven project with the 30 years' experience to bring awareness, whether it's about health, whether it's about education. Now, towards ecological question. How we can use solar energy in an appropriate way, how we can use communication technology to escape from this too much top-down-driven hierarchical systems to give the chance for a dynamic development of rural areas. These are our aims in BJ Institute, but we are still in the initial phase. It will take a while, and it needs the right partners, and it's so difficult to deal with the Indian government on a state level as well as a national level because they have a very much top-down approach. They think we need to bring vocational training to two hundred million, three hundred million, in ten years, so they think, 'Oh, we'll buy the best curricula and we roll it out to millions of people,' but that's not the way, brings the results, as per our experience. I think we need to work far more with a bottom-up approach to, not by the same way of selecting the most brilliant people with learning by ear and passing multiple-choice tests. In multiple-choice, in a way, we do the qualification today. You will get as a result the best reverse engineers who can understand the psychology and the technical needs to organize exams for hundred thousands of people, those who understand it, those who have clear look at, How many points I get by what question, and how can I understand what was the intention of the writers of the test? They will have the best chance to pass the exams, I tell you as a chief expert responsible for a qualification process under real conditions. So that is, in India, even more. So we want to encourage people more like sport clubs in competition, in developing their own abilities.

[Federica]: Can you give an example of an activity that the kids do?

[Bruno]: For example, all the students have mobile phones with weak batteries, and the more rural the area is, you have sometimes seven times a day power cuts, sometimes you have only for a few hours a day, even, power in the system. So when you make the experience with fifteen years that you're not depending on anyone, that you can generate your energy for your mobile phone or for light to read at night or watch TV or whatever, and you are not depending on the electrical company, you are not depending on the schoolteacher, you're not depending on your parents, that's a learning for life. Then you learned that saving energy is gaining independence. So this type of experience, we want to plant in young people that they learned something for life, and they can scale then their experience into a industrial or into a small-scale industry area, if you understand watt, volt, and ampere, if you understand the basics of solar energy, you can scale it up immediately, if you got it. What are the critical factors? So we work with batteries from motorbikes, 10 euro a battery, but it gives you a few years' service, and panels, 10-watt, 20-watt, not big things, but then when you limit your consumption of energy, when you understand how much energy is flowing in, how much is flowing out, you understand more than if you learn theoretically about all these aspects. So that's the way we go. And this type of experience, we want to roll out, and we have used memorandums of understanding with the local government, but another problem is, in India government can take a decision, but this doesn't mean that they have the resources, and it's complicated in the administration [line 01:14:03]. So that's the field we're working in. And all this is to prosecute the future activity of the Rural India South Development Trust, moving from health, education, now to developing the local resources. And one thing is for sure: If you look at the big cities like Delhi, Bangalore, Hyderabad, there is a cloud of dust over the cities, and the rural areas have an advantage. One of the rare advantages, if you compare rural areas to the city, is better possibilities to generate renewable energy. So we're going into that field.

[Federica]: To bring this interview home, I would like to ask you one last question that I think connects the first part where you spoke about the art museum Basel and your work in Switzerland, and the second part where we moved to India and you spoke about your work there. There is a key word that connects these two parts, and that is 'quality'. Quality is the key word that caught my attention when I first heard you speak at that conference in Brussels a few years ago. The way in which you were explaining how you implement your projects made me feel that you were approaching this in a different way, different than the implicit usual way of the first world. So digitization requires lots of resources, skills, people, time, so it's expensive, and it's a business too, and it is a good thing that money - and also big money, sometimes - have been put into digitization, including in building large infrastructures. There are some notable examples, and that's a very good thing. But where I'm going with this, with quality, is that we in the First World - I think - get this misconception sometimes that just because you have a lot of money, you will do a great job, so if that project got a stellar amount of money, then, wow, their output will be amazing. And while that's oftentimes the case, for many reasons, but it's not obvious, so just because you have the most expensive scanner, for example, in the work in India you just described, that does not mean that your archival copy, the digital master of the original object that you're digitizing, will be of top-quality. You need a methodology. You need some principles. Maybe there is philology involved. There are many other factors involved that are precisely in a way not technological. It's about understanding the content. And so I'm interested in hearing you elaborate a little bit on this concept of quality, as you understand it in the project that you implement in India in an environment that's so different from [standard 00:17:20] Europe for example, where then the similar or equivalent cultural heritage materials cannot be taken care the exact same way. So with limited resources, how do you still ensure quality? How do you define it, and how do you implement the project, and also, well, what are the factors that play against that? What are the main obstacles of carrying out a digitization project in India as opposed to, for example, Europe?

[Bruno]: Maybe by the things I was telling now, you could imagine that I made a lot of experience in different field on the one side here in Switzerland, where investments are not so important because you can expect somehow they will be there, on the other side in India, where I see that a lot of money is wasted because they try to act the very same way like we do, but we have a very stable climatic situation for machines and equipment, and this is not always given. And then you have people who really believe when they can afford the $200,000 scanner and operate the same, then this is quality what comes out. But if you look at it in practice, you will find out that such a scanner immediately will break down because of the dust in the air, because of the fluctuation of the energy. Then you have to capsule the whole thing, you have to separate it from the power supply, you have to separate it from the dust in the city. And so that comes another $100,000 thing, all the infrastructure. You have to use a diesel generator in case of power cut and things like that. So that ends up everything into big spending, and when the project is over, the people did not really learn something because they had been push-button type of work. They organized the material to be captured and pushed the button, and everything else was just engineering from the machine builders. So we understood that the latest generations of digital cameras are so good that about 10 years ago, you had to spend 1 million, or 20 years ago, 1 million dollar to get the same quality. So you have to control the light, you have to use good lenses, you have to control the environment, but this is not risky, and consumption of energy is very limited because these cameras are made to be mobile, so they are so well covered from dust, and if you use them hanging, they will not be affected by the typical dust cover. And so I understood with this type of technology, you can digitize from the glass plate of historic photography up to the fieldwork in an archaeological department, because if you learn factors of quality and if you learn it from the scratch, you will be flexible, while if you spend all your budget to control technical aspects, the people will be left unemployed when the digitization of your ancient material, historic material, is over. So naturally, my aim is to empower the people to, rather to train them and try to give them the opportunity to make their experience [within 01:21:14] always because they have so many different materials, from a coin collection to the documentation of historic temples. And so when they understand their tools and the demand, they will be employable in future in other fields, but when they are just push-button specialists, they are just depending on the technology they are trained for. So that brought me to the point where I think it's a better investment to train, basically, and to use long-during equipment than to go for too-high-specialized material which is depending on many other factors, such as dust control, power supply, things like that. And the results are amazing, because people, they are then coming back to what we said in the very beginning. The people then are more motivated. They develop that type of pride because they understand what they do, and if you are just a push-button specialist in a very expensive machine, it's a little bit difficult. You can be very proud of pushing the button on a very costly machine, but that's not for long.

[Federica]: Bruno, I would like to thank you so much for taking the time to be on Technoculture. I thank you for telling us a bit of the many different things you do. I always appreciate this attention for meaning, attention for people that you have, so thank you for telling us a bit about that. In the description of this episode, we will put the link to the BJ Institute with your email so people can get in touch with you if they want to contribute...

[Bruno]: Oh, please. Yes, yes.

[Federica]: ... to your work in India or get more information about your activities. Thank you so much.

[Bruno]: It was a pleasure, thank you.

[Federica]: Thank you for listening to Technoculture. Check out more episodes at technoculture-podcast.com, or visit our Facebook page @technoculturepodcast and our Twitter account, hashtag Technoculturepodcast.

Page created: March 2019

Updated: September 2019

Update: September 2020

Update: October 2020

Last update: September 2021