Scientia vincere tenebras: The man behind the robot orchestra

with Godfried-Willem RaesDownload this episode in mp3 (46.92 MB).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

I've been a great fan of God's since I first attended my first performance at the Logos Foundation in Ghent in 2015. He's a unique character and I hope you will come to know him better during this interview, in all his aspects from artist to intellectual, provocateur, organiser and performer. Godfried-Willem Raes is known worldwide as a music maker in the broadest sense of the word: as a concert organiser he's been responsible from 1973 until 1988 for the new-music concert programming of the Philharmonic Society at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels, in addition to which he also organized and still organizes all the concerts which take place at the Logos Foundation in Ghent, in total about 150 international new music concerts a year.

Godfried believes in sharing: his website is rich in information on the Foundation, past performances, the robot orchestra's tech specs, scores, audio and MIDI files... there's so much you can get lost in there, but keep digging, you'll end up reading something mind-blowing that took place ten or twenty years ago and you'll think: why didn't I know about this before? Quite remarkable, give it a shot.

Godfried-Willem Raes studied musicology and philosophy at the Ghent State University as well as piano, clarinet, percussion and composition at the Royal Conservatory of Music of Gent. In 1988 he became a professor of music composition at the Ghent Royal Conservatory. In 1997 he also became a professor at the Orpheus Higher Institute for Music, a commitment he held until to 2009. In 1990 he designed and constructed a tetrahedron-shaped concert-hall for the Logos Foundation in Ghent, a project for which it received the Tech-Art prize 1990.

Next to his reputation as a composer, he is also a well known expert in computer technology, robotics and interactive electronic art. He holds a doctors degree from Ghent State University on the basis of his dissertation on the technology of virtual instruments of his design and invention. He is the author of an extensive real time algorithmic music composition programming language: "GMT" running on the Wintel platform.

He is currently the president of the Logos Foundation and general director of the Logos Robot orchestra as well as Associate Researcher at the Orpheus Research Centre in Music (OrCIM).

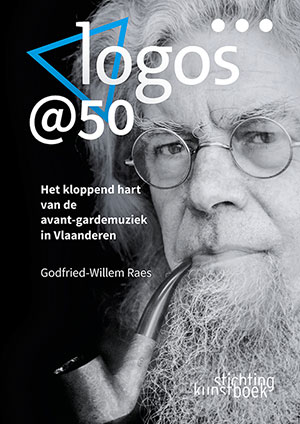

The Foundation celebrates 50 years of activity this year, 2018! Godfried wrote an extensive book on the Foundation's history... but I'm afraid it's only for Dutch speaking readers.

Check out the website of the Logos Foundation for much information and multimedia goodies in English: http://logosfoundation.org

Go to interactive wordcloud (you can choose the number of words and see how many times they occur).

Episode transcript

Download full transcript in PDF (130.90 kB).

Host: Federica Bressan [Federica]

Guest: Godfried-Willem Raes [Godfried]

[Federica]: Welcome to a new episode of Technoculture. I'm your host, Federica Bressan, and today my guest is Godfried-Willem Raes, founder and president of the Logos Foundation, Flanders' unique professional research and production centre for experimental musics, musical robotics and audio art. Welcome, Godfried.

[Godfried]: Thank you.

[Federica]: You are a true Renaissance man of our times. You are well-versed in so many different domains, but music is definitely a common denominator. Could you please introduce yourself and tell us about your relationship with music? What are you about, Godfried?

[Godfried]: Well, from very early on, actually, when we started, before we started, before... I was fascinated by sound as a way, as a tool, for expression, but nonverbal expression. And for me, early on, music was not just about playing scores, existing music, imitating musics being pretaught by others, but how can I use sounds as an expressive tool without any semantics, without referring to an outer world? So sound just as referring to formal concepts of our mind, either that or expressive things, emotions if you want to narrow it down, things like that. So I thought, to do that we have to develop tools, because this is not the standard practice at our conservatory and music schools, because at the conservatories you're taught the technique of mastering a given instrument to use that to realize existing scores.

[Federica]: You stress that you are interested in the nonverbal aspect of communicating with music, but isn't music the nonverbal sonic language par excellence?

[Godfried]: Of course. Of course it is, but it's not always free expression. What they want you to do at a conservatory is express yourself through a given, mostly historical, text. You play Beethoven, etc., and then you can project your own emotional world into that score, which also means sort of a decapitation of what you really want to do, because you have to conform to the areas of expression provided within that score, within the constraints of that score. If you want to go crazily wild in the Appassionata, you can't do that because that's not in the notes, so you have to enter, to identify yourself with some part of music history. This is an extremely conservative attitude, of course. It's very good for keeping the tradition within a culture, because if you change every five seconds, of course, there would be no tradition, and even probably the notion of culture would cease to exist. But the thing is that by repeating the past all over, you actually limit the expression of the individual very, very much. Not only that, you're also limited by the tools that are given to you for this kind of nonverbal expression that we call music. If you are supposed to express yourself on the piano, you should always realize that the piano is an instrument invented, well, 18th, 19th century (there is some earlier things, but okay, basically that), and that piano is optimized for a certain repertoire, for certain music, music taught, for instance, in equal temperament with 12 notes an octave. So you think of music that goes [sings non-tonal music], you're not helped by this piano, because the piano will frame this in the 12 notes, etc., that you have available there, only with that material. Clearly, there is nothing wrong with a piano, but it's a tool for the expression of a certain epoch of music in our culture. I think every time you have to reconceive and rethink the tools of musical expression that we use, and it is in no way evident to use these old tools in the 21st century. I find it completely not normal. There are still people playing the violin, for instance, because the violin is optimized for tonal music. It's tuned in fifths. It has its awkward position. It's very unhealthy, by the way. It has all sorts of problems with it. Why would we still use such ancient tools other than for repeating the past? Because it's clear that you're not going to do Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto on something else. Of course. It must be violin. But if you now want to express yourself now in our time, it is in no way evident to use the violin.

[Federica]: There are two things that I'd like to say to you as a response to what you just said, and maybe then you can elaborate further. One is, I understand the frustration or the will to break free from the boundaries of the traditional instruments, but didn't we have this conversation a hundred years ago with the Futurists who started challenging the concept of music, of sound itself? Noise acoustically is sound, but it wasn't obvious that it would be legitimized as compositional material. So why are we still having this conversation today in these, seems to me, exact same terms? And number two, breaking with tradition in terms of tonality. This is also something not new. This is even older than a hundred years. Well before electroacoustic instruments came about, atonal music was exploring the realm outside of tonality, and it was perfectly played on the traditional instruments. Then electroacoustic instruments made it possible to include the sound spectrum in the composition as a compositional parameter. You could compose your own sound, sure, and now digital instruments basically make this possibility available to everyone. So what do you mean exactly when you express this will to transcend tonality? Haven't we done this already to the extent in which it was doable, because the rest of us, who listens to popular music, is used to tonality, and pop music shows no intention whatsoever to move away from tonality anytime soon. So what do you mean exactly by that?

[Godfried]: First of all, to remark, going back to the Futurists, it's clear that I'm not the inventor of the thought of free musical expression, nor of the thought of using new tools and developing new tools for that expression. Of course, it connects, and it all started, actually, in the Futurist mostly in the Futurist era, because that was at the source of it, and we were just a continuation of that thought. It has been ongoing since then. As to your reactions to all the classical music being tonal, of course, but pop music also being tonal, the question is, what is in our culture the role of different musics? And I think pop music has a very different role. It's not really about music, I think, so much, because if you would take it from a musicological point of view, I do an analysis of pop music, you always have I-IV-V, I-IV-V, and 4/4 metre, etc., always the same over and over. What changes? Well, the sounds, the videos around it, the visuals, the sexual components in it. That changes stylistically very much over time, those elements, but the music [in se 00:08:17] there is no innovation there. And it's clear why is there no innovation: because it's a product on a market. It's something that sells, something that people pay for, etc. And they don't do it for musical analysis or anything like that. So innovation within pop music is, in my opinion, barely thinkable, and actually, if it exists and it exists to a certain extent it becomes marginal to the pop music because there are clearly people that belong to pop music and have replaced borders, but it's not followed. For instance, people like Aphex Twin or... Well, there's many Sonic Youth and things like that but they are borderline phenomena in pop music. What we do not see is that these groups that are deviant in their stylistic approach influence the mainstream. The mainstream stays what it has ever been, and apart from the sound, there is not much difference between songs from the '60s and things now. Maybe some, like techno, but still, techno is not mainstream. That's marginal within the pop music scene. That's not what makes big sales. Now, that's one thing. So the role I always took is actually a continuation of a longer tradition of the effect of making what I call art music and contributing to the development of tools for musical expression, and that's... It's not popular and doesn't have to be popular. It's certainly not mainstream. It will certainly never be mainstream, neither, so it's not my hope that by repeating avant-garde or experimental music, I will ever make big sales. I don't have that hope. Neither has a mathematician the hope that his articles will be read by millions of people all of the sudden because they invest a lot in mathematics. There's nothing wrong with things that work on a small scale. There is nothing wrong with laboratories, with experimentation, development of tools. I think measuring it by the number of people that are interested is a wrong point of view, is a wrong starting point.

[Federica]: How did you materialize this will for exploration into your career? How did you translate it into practice? How did you embed it into your works?

[Godfried]: Oh, I started, early on when we started with Focus in the late '60s, it was electronics. I made a lot of, designed a lot of analog synthesizers that were specially designed for live performance because it was sort of protest against the electronic music studio, was very much in all the universities and radio [institutions had an 00:11:00] electronic music studio etc., but from my point of view, those were very bad tools, in fact, because there wasn't spontaneity. You could only make, realize, tape products and then broadcast it or, well, put it on loudspeakers in the concert hall. The whole performance aspect, the whole idea of musicianship, went completely lost. So that's why I was interested in live electronics so that you could play the electronics on stage, if possible, with as much as possible bodily contact with the electronics. So I'm not the only one did [unclear 00:11:39] for instance, it's also open circuits that you could touch so that there would be some bodily involvement, because with traditional electronics like a commercial synthesizer, you have lots of patch cords, knobs and buttons to turn, etc. and you're actually far, you kept far away from the electrical part of the circuits. That was considered dangerous, don't touch it, etc., so that was not the musician's part. That's the subversive aspects of not only my work, but at those times certainly was in my work, present in my work, with this bodily involvement in electricity and feeling the electricity even through your body, that way playing the circuits. But that was the beginning was electronics because, of course, when we started with Logos and we started realizing that the old instruments were not the perfect tools for new musical expression, what was the hope? Electronics, because that was the thing of the future. Of course. Everybody wanted into there. After a while, we started realizing that electronics were very crippled musical instruments. First of all, because they cause a lot of dissociation. If you use electronics, you have to use loudspeakers, and if you use loudspeakers, you have a big liar on stage, because what is a loudspeaker? It's a paper cone driven by an electromagnet that pretends it is everything except what it really is. You can make it sound like a violin. You can play a piano on it. You can do whatever. But loudspeaker doesn't reveal the slightest thing of the source of the acoustic source that you are perceiving. So that's why I'm saying a loudspeaker is a liar. Now, that's not a problem [in se 00:13:20] because for reproduction, that's just fine, but it undermines musicianship because it adds a layer of dissociation between the actions you perform on stage and what the audience really hears, because you turn the knob, etc., and the loudspeaker does something, something. The relation between both is completely obscured. This is not the case with a violin. A violin is very direct. You touch a string, you bow it and say, use... The relationship between the manipulation of the violin and the sound is obvious. It's almost... It's so readable. You can anticipate on the sound by looking at the movement of a violinist. You cannot anticipate on the sound if you play a synthesizer and turn knobs, etc., because you could just be preparing a batch and later on you push a button and then it goes off, things like that. See, that's the problem with electronics, and that's where, first of all, I started in my research and I think that's the original part of my research, rejecting loudspeakers and going back to acoustic sounds and that where the robots come into the field. And secondly, for the performance aspect, the musicianship aspect, I developed my invisible instrument, which uses radar and sonar systems to capture body movements, to translate that via computer circuitry, etc., to map that on whatever output. In the last 20 years, it's always robots and acoustical outputs that are driven by gestures, by movements of real flesh-and-body people on stage in a relevant way, not sort of mapped on something with knobs. From the machine, so if you hear a sound, you can trace it, you can find it, and it will always be a physical object that's responsible for it that causes the sounds, even though it is completely computer-controlled. But it's a mechanical sound, computer-controlled mechanical sound.

[Federica]: Logos Foundation celebrates 50 years of activity this year. Earlier on, in 2018, you released a book to celebrate this important achievement, and I understand we expect big celebrations next week.

[Godfried]: Well, big, pretty big. We try as big as we can, but we are a little bit handicapped by the fact that our subsidies were cut down completely, so... But yet, we are still capable of doing quite a bit of things. In the beginning of November, we will have many presentations with Logos projects not strictly concerts, but also things that are in public spaces, in libraries, even in hospitals, etc., installation projects, street projects, animations and also concerts, etc., all over the city of Ghent.

[Federica]: And the city of Ghent is home to the Logos Foundation, so you are a household name here. I think you're an icon, actually, of the cultural scene of Ghent. For those who know you a little less, would you like to tell us please the story of Godfried and Logos?

[Godfried]: Yeah, it came into existence sort of by accident, because in 1968 I wrote, at the conservatory, I wrote a piece, a composition, that was called Logos 3/5, that was on prime number relationship between the tempi that the musicians had to play to. It was a piece for five musicians, and for that piece I designed because it was very difficult to keep it metrically together an automated conductor, which later on became actually my first robot. Now, that piece, at the conservatory where it was performed, made a big scandal, and we were, to go short, all thrown out of the conservatory because with such music you could never make a career, they said. 'You have no... You're not gifted for music.' And all the Logos people were thrown out, but we stayed together, and well. I went to the university, studied musicology and philosophy and some more things, etc., so the conservatory was completely put aside for at least 15 years. I played no role anymore in what Logos did, but we were very active. We went on tour. We started picking up repertoire, international repertoire, from avant-garde music, made our own pieces, made our own instruments. We organized concerts. This is not just by chance. It is because, being in Ghent, we felt, with our contemporary music attitude, very isolated. There was barely anything else apart from the university studio, the IPEM, at that time. There was basically nothing, so we said, 'We shouldn't do this on our own. We should have international contacts, and the best way of having intense international contacts is, of course, inviting colleagues over from abroad.' So I got a small budget from the university to organise those concerts, etc., and to invite people to do concerts in Ghent, and then we had close contacts and so made friends, and we build a complete network, all of which was very, very international, in fact.

[Federica]: So the conductor of your Logos composition became your first musical robot. When did you start thinking, 'Oh, I could make more robots now. I could have a full robot orchestra'?

[Godfried]: Well, that's much, much, much later, because when I designed the automated conductor, I didn't think of it as being a robot, although it was a programmable machine. It was just a tool for keeping my musicians together, and then, as I said, I went through we went, with Logos through a long period of electronics and electronic sounds, and we don't call analog synthesizers 'robots' in any sense, because there's no moving parts. There is no... Well, there's no automation, no motors, no mechanics nor anything. Those were just synthesized. And we've done that for about 20 years, and it's only at the very end of the '80s actually, the first robot is '89, the saxophone that I started consciously designing specific musical robots or programmable acoustical machines, and [from then on, 00:19:27] it took off, and in those last 25, it's a little more than 25 years, I've made some 73 robots already, so it's quite a big orchestra.

[Federica]: What I find interesting is that you haven't just made one robot and then another and then another. You actually thought of them as capable of playing together, so not instances, but actually a group.

[Godfried]: It's an orchestra. They're all networked. They can communicate with each other with [gestures 00:19:55] and they can watch at the movements, the gesture of performers. They can listen to each other and to musicians' inputs, and all these things are possible with the robots, yes. That's the idea, to have a really interactive [unclear 00:20:10], not just a playback machine. Otherwise, you wouldn't go any further than what was already possible by the end of the 19th century with the orchestrions and the [unclear 00:20:21], which could also play from a roll, etc., in a more or less sophisticated way, although without much expression. With modern techniques, it's possible to give all these robots the full range of musical expression, like going pianissimo, etc. Now, with these old machines, they worked with punched paper rolls, so you had either a hole or no hole in the paper, so the note was on or it was off and nothing in between. You had no velocity control, as we say in MIDI terminology. So actually, no expression other than timing, but that was about it. Now, with these robots, the advantage, you can do virtually anything in terms of dynamics, in terms of speed also, so they overclass what human performers can possibly do. The example is very trivial. If I take my piano, first of all, it has 88-note polyphony, so we have only 10 fingers, so there it beats the human performer, that's clear, but also it's capable of having individual dynamic control over each finger. Now, human hands can do very much and are very subtle, but you will never succeed playing anything reasonably fast with each finger in another dynamic. We simply do not have the muscles and we will never develop them because we simply do not, anatomically, we do not have them. This is beyond the possibilities of humans, so also on the expressive potentiality, these robots go further than what people can do. It doesn't apply to all robots, though, because for some there is still big trouble in development. For instance, string robots are very difficult, string instruments, and although there are many attempts in the orchestra to make such instruments, there I have to be more modest, but on the other, the organs, it's more than perfect. The piano is also, I think, near to close to perfect. The wind instruments are very good, and you can do all sorts of inflections. They can also play microtonally, etc. The only capability that's very difficult to implement, that's multiphonics, but, okay, those are actually not common sounds.

[Federica]: The robot orchestra can sound in many different ways. There's not just one type of sound that is specific to the orchestra, and it can play in many different genres. But let's listen to one example of how it can sound. We're going to listen to a short excerpt now from a composition which is...

[Godfried]: Lonely Robots. That's a piece that I wrote for the hurdy robot, which is a hurdy-gurdy, yeah, an automated hurdy-gurdy, where I did an experiment in overtones, etc., and you have two versions of that piece, a platonic version which is according to the so-called just overtone series and it doesn't sound at all. It doesn't work because it's not conformed to what the physics dictates. And then I made a sixth, second version, Scientia vincere tenebras, where everything is correct, but it's not just intonation anymore because all the proportions of the overtones are irrational numbers. But at least it sounds nice.

[music: 'Lonely Robots' by Godfried-Willem Raes]

[Federica]: What you do is clearly very creative, both the instruments and the compositions. Is it art? What is art, Godfried?

[Godfried]: The question whether it is art, for me, is not a very interesting question. Actually, musicians do not have to deal with that question too much, because it's music anyway, and whether music is art or not art music is a sociological question, finally. Research is something else, and science is something else, because there you have results, etc., but I have a whole theory on our so-called team of artistic research. For me, the only research part that you, from an artist point of view, can do that makes sense to do has to do with the development of tools of expression, because, as an artist, you use these tools. You're the first user, so you're also the first one to develop them and to judge on them, to evaluate them. I think scientists could not develop a musical instrument. You have to be a musician in order to do that, because a musician understands the needs of the instrument, not a musicologist, not an engineer. So for me, that's... I think even the whole area of artistic research should be strictly limited to that aspect, because other things, artists are just not good at, like cataloguing of writing music history, etc. That should not be left to artists. Writing so-called artist texts is generally bullshit. It's generally just verbs, verbs, verbs, and nothing concrete, nothing that can be tested, whereas make, developing tools and contributing to the development of tools is something that is testable, is controllable. Just like anything, science should be controllable, repeatable and, well, checkable.

[Federica]: Besides the development of tools, there can just be a reflection, so an artist can not just make things, but also reflect over things, and that can be part of his or her work.

[Godfried]: Oh, yeah. Sure. Never said that all machines that you develop, all tools you develop, ought to be physical tools. Of course, it can be mental tools. It can be algorithms for composition, for instance. There are pure formal structures, either software or just actually on paper, as thought machines. Of course, that's also part of the kits of tools available to artists. I think it's essential. It's not the only material, robots or instruments.

[Federica]: Okay, so there is always a pragmatic element built into artistic practice. Can then maybe a difference with science be that researchers normally start with a research question that determines every action that is planned afterwards? If everything goes 'well', quote-unquote, you have solved a problem. You have answered that question, whereas if something unexpected happens, that is where you leave the door open to accidental discoveries, etc., so serendipity is definitely allowed for, but it's not really built in the process, whereas I see artistic practice as more free, less bound to the specific goal. It's more like, 'Yeah, let's find a direction we want to go to and start moving towards it and see what happens.' If you know what I mean, artists can keep an open mind, in the best sense, in a different way than a researcher can do. What's your take on this? Do you see art as being less bound by a research question?

[Godfried]: Oh, no, I don't think that there is no research question. There can be a very... For me, in any case, there's always a very clear research question. If I develop a piano with a certain purpose, I want it to be expressively more capable than humans. I have to clearly define what is expression on the piano. I have to give an analysis of this. I have to say also against what I am going to measure it, so that would be no research question... No, no, no. I don't think artists that work in the wild on their intuition and associations ever will do any kind of research work. Research work presupposes a question, a problem, but I think any serious artist has problems all the time. Otherwise, he's a craftsman. He performs an art that he has learned and performance may be better and better over the years, but he is certainly not a researcher.

[Federica]: Does science inform your art, and how?

[Godfried]: Continuously. First of all well, not only science, also technology. You have to take the broad side because, since I work a lot with electronics, it is clear that every time a new generation of microprocessors comes out, this has advantages and will be applied and find applications in new designs that I make. Now, you can say, 'Oh, but that's technology; that's not science,' but actually, that goes pretty much hand-in-hand, because if we develop new microprocessors, new algorithms become possible, and those come clearly from the pure science point of view. Actually, many things, there is a close link between technology and science. Think, for instance, of the development of special chips for fuzzy logic. Fuzzy logic was developed, scientific thing from mathematics, etc., and then was applied to electronics, so there is implementations of fuzzy logic on chip level now, and these are available for people like me and people in industry, of course.

[Federica]: And this collaboration with science was encouraged, was facilitated by your contact with the university since the early years of Logos.

[Godfried]: Yes, certainly, because, as I said, we were thrown out of the conservatory, and then I went to university and I was not such a bad student. Also took special classes in math and, you know, electronics, and yeah, yeah.

[Federica]: And do your robots reflect these 25 or so years of technological evolution?

[Godfried]: Oh, clearly, clearly. Also, people forget often that these robots are not something you make and then it's finished forever. Many of these robots, particularly the older ones, went through many stages of upgrading. For instance in the first, if you would see pictures of the first version of the robot orchestra, you will see that each robot had a laptop to control it on its own and it was connected with a flat cable from the printer port of the laptop to all the electronics, and then the computer laptops were connected in a network. Now, it was a pain in the ass after a couple of years. First of all, because all these laptops wanted to upgrade to another Windows version, etc., so... Well, there was always a risk involved. 'Let's pray that they don't want to do an upgrade at the concert, because that stops everything,' etc. It was really a pain in the ass. But at that time, there was no alternative because the microprocessors available were small 8-bit machines with a clock frequency of some 8 megacycles at the very most, etc., and could just not compete for network operations before the laptop could do. So that was an alternative, but it took only a few years and ARM came out, PIC came out, and many microchip, and many brands came out with powerful microprocessors, [unclear 00:34:05] fast machines, 40 meg or something. And then I started rebuilding the machines and incorporating microprocessors in the robots so that we could get rid of all these laptops. So now we have just one single server to control the orchestra and every machine is completely autonomous and has its own microprocessor systems.

[Federica]: Celebrating 50 years of Logos Foundation and even more years of experience, what's your take on today's scene? What is your perspective, especially on this combination of art and science? Even 'art-science' is one word being in trend now. Artists visiting research labs and researcher being well, receiving the input of artists to expand the horizon of their research approach. What are your thoughts on art and science as characterized today?

[Godfried]: I don't think art and science is such a novel thing as a combination, maybe in terms of public appeal of... Well, see, if you think about the topic, think about someone like Lev Termen with the Theremin. This was very much at the edge of technology in the very beginning of the 20th century. Stokowski has done writings where he anticipated on seeing the whole future of music in electronics, etc., and then we are speaking of the '20s of last century. So it's not such an awful thing, but I must say, in last years, there has been a stronger focus on it, and that has to do by the fact that the music scene that is involved in these technologies has gained in a certain way the status of Its own, because I think in the mid-20th century, it was absolutely marginal. It had no position whatsoever. There's many things written in books about it, but if you see the role that it plays in music culture, it was marginal. What we see today is that there is no music culture anymore. Well, in the mid-20th century, to simplify things, you had classical music and concert halls, etc., you had pop music, things that were sold in 78 tours disks, etc. came out every week, a new one and things like that, and you had an upcoming jazz scene with a public of its own. That was... I'm simplifying, but that was basically the scene. What we see now, the classical music culture, well, I exaggerate, but it's sort of dying out. You see, the public is getting older and older and older, and it's... You don't have to be, well, clairvoyant to see that in a couple of generations it's going to be done because the public will just die.

[Federica]: Oh, but aren't there so many young musicians, talented musicians, being trained in classical music? There are competitions, CDs. Like, it's a lively scene.

[Godfried]: It's pushed very much, but still, look at the objective numbers and not the propaganda, etc. It's going down. All the theatres, they get renovated, renovate the theatre in order to have less seats, etc. so that it's easier to sell out. Also for the theatres, by the way. Theatres are doing it also massively. Now, they are reconstructing Bijloke hall in Ghent, reduce the number of seats. Of course, if you reduce the number of seats, it's easier to sell out, now, but... But okay, that was not my main issue. That's the classical music thing. If you take the pop music scene, it's never been so... That's diverse as it is nowadays, you have scenes for sort of everything, every subgenre. You have heavy metal, punk, I don't know, all these names, etc., and they all have specific audiences of their own. There is still a little bit jazz left also. It's less important than it was. Free jazz died and okay, it's a club circuit, but it's still in existence. You have... Well, for every musical genre, you have sort of a subcommunity that attached to it. Why do you have very little, it's in fact, crossovers, people that go from one to the other? I see no people from classical music going to a techno festival, or rarely.

[Federica]: I think crossover is actually a name of genre.

[Godfried]: Again, yes, yes, but I didn't want to mean it in that way.

[Federica]: What's the difference between art, creativity, and craftsmanship?

[Godfried]: For instance, the notion of creativity is one of the most misused words that there is in common speech. For me, creativity is problem-solving, is where you have a problem and you find a solution for that problem that's not given, etc., so creativity is sort of opposed to craftsmanship.

[Federica]: What is then that spontaneous talent of someone who doesn't know what to do and is inspired to pick up a brush and paint a picture, or children that draw spontaneously? That's not problem-solving, or is it?

[Godfried]: That's expression. That's not creativity. That's expressive capability. Of course, people have them. People confuse expression and even original expression with creativity. Creativity applies not only to the arts, it also applies to science. If Schrödinger comes out or Heisenberg comes out with a new formula, that's a creative thing because he thinks in physics out of the box to design a new formula, etc., [unclear 00:39:52]... If Gödel imagines this strategy for his famous proof, etc., that's creativity. That contributes to the progress of science, but there is the problem. There are artists, can be creative. Some are, but you're not creative all the time, because if you find solutions for certain problems... For instance, there is a creative moment, to give an example, in the arts. In Cubism, if you want to have different facets of reality at the same time in a painting, well, that's where Cubism came in. You have the two planes in one and the single painting. If the Futurists for the first time tried to express movement in a painting, they took probably the idea for photography: You have many times the same image a little bit shifted and you have an illusion of speed. That, for me, is a creative moment in the development of the arts: this thing. But the fact of painting well and painting nicely, there is nothing creative about that. That's craftsmanship, or that is expression, if you want. It's craftsmanship in as far as it shows your mastery of existing recipes for expressing yourself within whatever medium you're using. So for music, for instance, it has always meant, at a conservatory, mastery of classical harmony and counterpoint for composition, and for instruments, mastering the violin, play your scales fast enough, etc., etc. For piano, the same. There were all these exercises. That's craftsmanship. There's nothing to do with creativity whatsoever.

[Federica]: Although someone who is expressing something can be creative while doing it, no?

[Godfried]: Depends what problem he is solving. You cannot tell that from... Then there is no distinguishment, of course, because I would use 'creative' only in as far it has social relevance. I mean, you can be, of course, creative on your own in your little ego by changing the boundaries of your knowledge, etc., but if your boundaries are very limited, the social relevance, the cultural relevance of your creativity will be very limited, also. So I would be careful in calling that too much, stressing the creativity aspect too much in that, because if a problem has already been solved by someone else, there is just no merit to it. And the other thing is, of course, the other notion that you mentioned is, of course, research. Now, research is just a question of methodology. Of course, it needs... Research needs research questions just like creativity needs research questions, but not all research is creative. Some research can be very, very like craftsmanship, very much like craftsmanship. For instance, suppose a musicologist wants to know how much percent of the population listen to rock and roll, etc. That's a scientific question, and you have to count listeners and do enquêtes and forms, etc., to find that out, but there is no creativity involved in that kind of research. None! It's just the craftsman of, according to the rules, scientifically do the methodology, etc., and come to your results. It's nothing to do with creativity. It's craftsmanship, just like someone who plays a piece for the Elisabeth Competition on the violin, it's craftsmanship. It has nothing to do with creativity. There may be expression, but these are separate elements, and they can combine in some forms, but we have to keep the notions more or less defined, clearly defined and apart.

[Federica]: Do you think that our society even lacks the words to describe a well-rounded profile? Like we don't have the box for the Renaissance man, somebody who is educated in philosophy, but can also build things? A polymath is not actual anymore, and if you are well-versed in many different things, you're actually perceived as a fragmented person, because these types of characters are rare today, don't you think?

[Godfried]: That's what I see, because it's encouraged also by the scientific and cultural politics. If you enter a project, it also has to be very well-defined within the constraints of one's certain discipline, etc. Things that go over borders are generally rejected in terms of proposals for grant applications, etc. You barely can do that because you have specialized committees, etc., and if you don't conform, you fall out of it, and you're... If you want still to want to do that, you have to work on your own, pretty much, and fight your own way through things, and it's much harder.

[Federica]: Fifty years ago, as well as today?

[Godfried]: Well, fifty years ago, because there were barely any structures at the beginning. It was in a certain way freer, but at the other end, there were no means, because now we... There is a politics for a subsidy for all sorts of things. Well, before 1985, it didn't exist in Belgium. There was no rule system. You could apply to the government with political support to get funding for something, but it was not based on the law system, on rules of any kind. It just depended on who do you know there, and who is going to eventually support you? So the advantage was that you could come out with something completely out of the box and get a grant for it. Now, these chances now are much more. For instance, to give you an example, they did [cut 00:45:34] a subsidy for the Logos Foundation because you, on the forms for the grant application, you have to fill in lots, tick all, check those checkboxes. You have to know, are you a concert organization? If not, you're a production centre? If not, you're distribution or you're publication, you do philosophical thinking, you do reflection, etc.? If you, like we would tend to do, check all the boxes, they say, 'You're a fool. You can't do that.' So we cannot have philosophical reflection at the same time be a production centre and do receptive concerts. Now, that's impossible. Then you're rejected on that ground alone already, so that's what's so insane about this system.

[Federica]: Lagos does not coincide with the robot orchestra, although it's very famous for it. Logos does many other things.

[Godfried]: You've now been talking about music and mostly focusing on instrument development, robot development, and things that are presented for audiences in the ritual that we generally call a concert where people come at a given time, etc. But Logos has been doing many different things interactive projects in the air, in public spaces, and things like that which are not concert projects. For instance, the Singing Bicycle Symphony, that's something with prepared bicycles where people pass [away 00:47:03], etc. and that's a strange thing for people to see. But nobody has ever heard it because you cannot hear it unless you participate, and even then you don't have, think... It's flashy. It just happen. Or the other project, Tram Stop, Halte in Dutch, where I amplify the rails of the tramway and have loudspeaker at the pole where people wait for the tram so that you can hear the tram coming before you see it, which is an old idea from the American Indians where they put their ear to the ground to hear whether horses are coming, etc., and later on they did it with the railway. So I made that into an installation piece. Now, that's not a concert. That's just something where people walk by and they say, 'Hey, I hear something. Oh.' Oh, later on, they see the tram is coming, because that makes a fantastic sound when the tram is coming. You see nothing. So that's something happening, something you do in public life and public spaces, etc., that attracts people's audience to some sonic phenomenon, to some sound phenomenon, and that's the whole purpose of it.

[Federica]: Now we are going to listen to an excerpt from Toetkuip. What can you tell us about this piece?

[Godfried]: Well, that's a very bizarre piece. It's actually a duet between a boat that's equipped with car horns, some 140 car horns, that are submerged under the waterline and that is actually a sound motor and it proves that with sound alone, your motor doesn't go very fast because the way of propulsion is by these immersed car horns, but it's a duet. Next to the boat, there is a bathtub, an old, ancient bathtub, with some 80 car horns immersed under the water line [unclear 00:48:50] and it's on trolley, on wheels, etc., and the score is actually that the boat and the car have to follow each other as much as possible. Of course, the car has to go in the streets, the boat, the horn, the tub with the horns and the boat, and they follow each... So they go wider spaces, closed space, you have all the echoes from the space, and the water is always shaky. That's why it sounds at times a little bit like pigs being killed.

[Federica]: So this is a live recording from the event actually taking place in open air. Do you remember where it was?

[Godfried]: I think this recording... I'm not quite sure, but I think this recording we did in Ghent, but we also did it in [unclear 00:49:53] in many different cities, actually, yeah, so it went on the road even in Torino.

[music]

[Federica]: Once, you were walking me through the large storage space here at Logos, where you have a lot of the materials and the equipment that you have used in your performances and events along the years, and there is one that I liked in a particular way. It was the SoundTrack project. Can you talk a little bit about it?

[Godfried]: Yeah. The SoundTrack project is another example of an absolutely not concert-oriented sonic event. It's where I made a machine a tape recorder, so to speak, but a tape recorder without motors. The propulsion of the tape for the recording heads and the playback heads is done by walking and rolling off big reel of tape, some five kilometres of tape on an immense reel, etc. Now, what happens is that you record at walking speed, but, as you know, walking speed is not a constant speed at all. It depends. If there is an obstacle, you will slow down a little bit. You'll be shaky. So although the sound of the environment may be cars that go 'vroom, vroom, vroom!' [barks like a dog] a dog, after recording with subjective walking speed, it sounds like [makes a variety of sounds] because, if the car passes by, you stop. If you stop, the recording speed goes down at playback, because playback happens on the same tape a few milliseconds later, the opposite goes. So every time you brake, you stop. The pitch goes all of the sudden, in a glissando, steep up, up to a full stop, because if you stop, the tape is not running and you're not recording anymore. Okay, that's one of the things. We have loudspeakers on our backs, so people can immediately hear the result of what that does, and then and that's the poetic aspect of it the tape, we leave it on the ground and we bury it on the space with an explanation to the people who say, 'Hey, it's sad that every space has a visual way it looks, but actually what it sounds like is never preserved in the space, so we will give the sound of this space back to the space by burying it in the space.' And we buried the whole length of tape, of the whole length of the [trajects 00:53:50] actually, bury it where [unclear 00:53:54] ground. If there is a stone, we have to stick it with stickers to the pavement and to the asphalt or something because you're not going to break the asphalt.

[Federica]: The tape got buried behind you as you went on, so you didn't go home and listen to the tape. There was somebody walking behind you and taking care of burying the tape.

[Godfried]: Yeah, someone follows, buries the tape, and the tape is completely lost, so we do not come home with a tape. No, no, no, no. Actually, there is another aspect to it. The signal from the playback heads of the recorder is also broadcast via an illegal FM radio station so that people that have ghetto-blasters in the park etc., whether they want or not, they have this signal and they hear it on their ghetto-blasters, so their portable radio sets, whatever.

[Federica]: This means that the tapes you buried are still there.

[Godfried]: Yeah.

[Federica]: And there where?

[Godfried]: We did the same project in [unclear 00:54:47] Ghent. Many times we did it in Antwerp, in Amsterdam, and along the Hudson River in New York all the way up from the Bronx and Harlem to Battery Park in the south.

[Federica]: So there's some Logos tape buried in New York.

[Godfried]: Possibly, yeah.

[Federica]: Who were you inspired by during your formative years? Who were you reading? What authors or artists, intellectuals, were you looking up to?

[Godfried]: Well, one of the first influences in terms of reading and digesting, although it was very hard at the age that I read it (I was 14) was Musiques formelles by Iannis Xenakis because he gave descriptions of formal musical formulas about how to draw music and do stochastics, etc., and I was fighting that book because at that age it was very hard for me. But for me, it was completely visionary because it was so opposed to everything that I was learnt at the conservatory. I said, 'This is really it.' And my first moment of exposure to this music is actually when I was six years old at the Philips Pavilion in Brussels. There was a world exhibition in '58 where there was this Philips Pavilion, where there was this piece officially by Varèse (actually realized by other people), and the architecture was by Xenakis.

[Federica]: Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait a minute. You were there? Poème électronique, '58, Philips Pavilion, like you were there? You have witnessed that?

[Godfried]: Of course, I was there as a child. I can tell you the story. It's a very funny story, because my parents were involved in a choir and we were supposed to sing there at Flemish days because Flanders was considered marginal in the Brussels exhibition. They wanted to present Belgium as a French thing. Well, okay, that's political, but so, because my parents thought I was too young at 6 to stay at all these rehearsals with the choir and the orchestra, they put me in children garden, but the ladies there spoke only French, and I was bilingual. I spoke Dutch and German, so I started crying the whole time but didn't understand, so they had very smart idea and they brought me (this little boy crying) to the Dutch pavilion. Now, that happened to be exactly the Philips Pavilion, and there, the ladies there took care of me, put me in the front row, etc., and I could sit all evening long, and I've done that many evenings in a row, sit and watch all these scholars, all these fantastic sounds there, and I was silent.

[Federica]: So, despite being so young, you actually have vivid memories of that.

[Godfried]: Oh, yes, yes. I have complete memory of that. Well, complete. I know there was [colours 00:57:33] and things and, well...

[Federica]: In what kind of musical environment did you grow up?

[Godfried]: Oh, strictly very conservative classical. No pop music allowed, etc. Only heavy classical music, Bach, Beethoven, Mozart.

[Federica]: And you were trained as a classical musician?

[Godfried]: Well, at age six, I entered at a conservatory to study the piano, etc. At that time, you could enter the conservatory as a kid, so it was considered part of a good bourgeois education, and I did sing in the choir also. That's why I can say in terms of classical background, I did sing the St. Matthew's Passion in all the parts. As a boy soprano, as an alto, as a tenor, and as a bass. Not many people can say that.

[Federica]: So when did your fascination for breaking the rules, pushing boundaries, came about? When did it start showing?

[Godfried]: Well, [I say 00:58:35] '58, Philips Pavilion plays a very important role there. It was my first exposure to something... It wasn't even presented as music as far as my... It was just something sonic and completely else. It had nothing to do with Bach or with the choir singing. It was just another experience and completely new sonic world. I found it fascinating, and shortly after, and I remember well that I never wanted to do my piano exercise, etc., unless the lid was taken off and I go see, could see the little ducks biting on the strings, etc., and then I started doing preparations. What happens if I withhold the duck? The duck with the little hammers, you know, with felt. So I started playing around. I found all these noises very interesting, and without having an example, I developed a feel for making sounds with this piano other than just by touching the keys and the practice, the exercises.

[Federica]: And your parents said, 'What's wrong with our kid?'

[Godfried]: Well... Oh, they actually didn't intervene pretty much. Only if it went too noisy, etc., then they would protest, etc., and then... And that was also before '68. I was fascinated by tape recorders and things like that, because I also had some contact with the IPEM studio around '65, I think. Yeah, '64, '65. I saw these tape recorders there and I wanted, at all price, I wanted a tape recorder myself, and so I built it. I did build one completely from scratch, with motors and everything, and I got that to work. And that was the first machine I used for making electronic music with.

[Federica]: Where did the knowledge about electronics come from?

[Godfried]: Oh, I studied that completely on my own, and I got fascinated by it because I lived, as a child, I lived just across the laboratories of the university in the [cellar of 01:00:28] Hendrik Consciencestraat. Okay, it's now Gustaaf Magnelstraat Street. And there was, in the bottom level, there were laboratories for electronics, for glassblowing, and things like that. But electronics lab was very fascinating, and I sat there with my legs down on the street watching to these engineers doing things, etc., always asking them questions, and one day they gave me a component. I got a... I didn't know it was a resistor, but I was very proud. 'Oh, I got a component!' And I told the engineer what it was and then the engineer said, 'Well, it's a component like they use in the Sputnik.' Now, the Sputnik, if you know, was a satellite that was launched by the Russians in '58. That was big in the news. The Russians were the first one to have a human object in outer space. It did only beep, beep, beep, beep, but okay. That was the first step. So I was very proud to have a component, and with the little money I had, I bought a little booklet about boys and electronics, and then I learned about what the components were, what those fascinating collar rings were on the components, how to read them, etc. I bought a soldering iron. I started making little circuits, first a radio receiver, because always all these books about boys and electronics start with making a radio receiver. Later on, I made a broadcasting station on the FM band, and there I got in trouble. I was 11 by then. Because I got... I didn't get arrested, but it was confiscated by the police because obviously it is forbidden, it is illegal to have a broadcasting station. And I just wanted to talk to my friend who lived a couple of blocks away, etc., and it was curious to know whether he could listen. Probably my station was causing a lot of interference with all sorts of other things, I presume something like that, but any case, they took it away. When they saw was just a little boy that did this, they didn't do anything. They warned my mother, 'Hey, you should do that,' but that was it, but I lost my station. But formally, I never studied electronics, but I have been doing... I did science directions at the secondary school, etc., but electronics properly speaking, no. Only when it came to doing my doctorate, it came out of, I had developed quite some expertise, because I did my doctorate on radar systems and sonar systems for gesture recognition, and there is a lot of electronics involved in there. So then it took the reading committee for my doctorate to call into the engineering department to read my thesis.

[Federica]: If someone happens to be in the Ghent area next week, can you repeat what they can see? The celebrations for the 50th anniversary of Logos.

[Godfried]: So for the weeks, occasion of the 50th anniversary of Logos, we will spread our interactive projects all over the city. We will have robots that have, are equipped with built-in radar systems that can be played by the audience. There will be projects that work on brainwaves, etc., where people, with a brainwave, control their own sonic environments. They get in sort of a capsule that's closed. It's called Stereotaxie. Now we have projects with water bubbles and objects that are submerged that you have to listen to with a stethoscope. This will be at Krook, I think. So there will be many, many places in Ghent where we're presenting. Some [pubs 01:04:10] will just show videos of all the robot stuff that's documented on video. There will be things in the museum. Well, projects everywhere.

[Federica]: Do you plan to document these events, make a video recording, so that people who can't be there or listen to this episode later than the first week of November can see something, look it up?

[Godfried]: Sure, some things will be videoed, and we will make sort of a report of it to broadcast on video. Videoing it live makes maybe not much sense, because the distance between the different places is large and you lose a lot of time, so we will make an edit that's representative for this aspect of the Logos work, I think.

[Federica]: We bring this episode of Technoculture to an end with an excerpt from one of your early compositions, something you did before you had the robot orchestra. It's called Shifts. Would you like to introduce the piece?

[Godfried]: Shifts, it's a piece, originally a composition I made for the conservatory students, but it was way too difficult for them to perform well, so I quickly, I made an electronic version that I later converted into a version for the robot orchestra and, well, it has gone through a whole series of revisions, actually.

[Federica]: What about the one we listen to now?

[Godfried]: This one, that's the electronic version which I made for samplers and synthesizers, which I realized and that was published by Experimental Intermedia in New York.

[music: 'Shifts' by Godfried-Willem Raes]

Thank you for listening to Technoculture. Check out more episodes at technoculture-podcast.com, or visit our Facebook page @technoculturepodcast and our Twitter account, hashtag Technoculturepodcast.

Page created: November 2018

Last updated: July 2021