A lifelong engagement with sound recording and audio tape restoration

with Richard HessDownload this episode in mp3 (30.97 MB).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

I first learned about Richard when the mysterious ways of the internet brought me to his comprehensive repository of materials on audio tape restoration, and I started referencing his scientific publications in my own work on magnetic tapes. It was quite a treat to meet him face to face in Culpeper, VA at the Library of Congress at the Audio Engineering Society (AES) Archiving Conference in June 2018. He is a walking encyclopedia on everything related to sound and audio, and a delightful conversation partner! I asked him to share his remarkable career path on Technoculture and this is the result. I am very glad this was an opportunity to know Richard better, and I am glad you get to know him too. He's the go-to person if you have old tapes that you want to save from oblivion, and that are giving you a headache because they stick, shed, warp or... bite!

Richard tells us about his early entry into electronics and provides an overview of the changes he's experienced in 55 years of audio involvement. He speaks to his experiences with the ABC Television Network, WABC-TV, his move to McCurdy Radio Industries in Toronto, and then to Glendale California where he spent 21 years at National TeleConsultants. We also discuss how he got into audio tape restoration and some of the challenges in storing and recovering tape. Finally, he unveils some details about his current project of developing, with John Dyson, a software decoder that is Dolby A compatible. If you're interested in archival storage and knowledge/information transfer... this is episode if for you. Thank you Richard for all the great work!

Richard's knowledge repository on audio tape restoration: http://richardhess.com/notes/

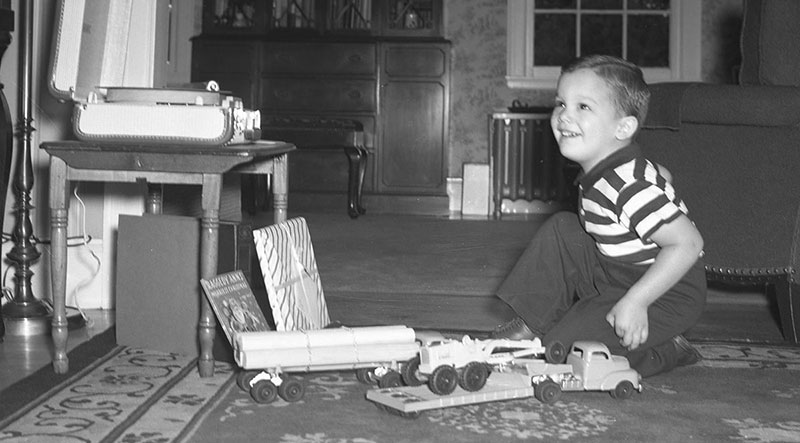

About the cute picture on the left, Richard says: "Note the phonograph on the table. I was hooked by my third birthday... We still have the little table (it's actually allegedly quite old), the needlepoint stool in the distance and the breakfront cabinet against the far wall."

TBS-Throw Back Sunday — in Forest Hills, New York.

Go to interactive wordcloud (you can choose the number of words and see how many times they occur).

Episode transcript

Download full transcript in PDF (131.06 kB).

Host: Federica Bressan [Federica]

Guest: Richard L. Hess [Richard]

[Federica]: Welcome to a new episode of Technoculture. I'm your host, Federica Bressan, and today I have the pleasure of speaking to Richard Hess, a person who knows a lot about audio, about recording, about audio restoration. Hello, Richard.

[Richard]: Hello, Federica. It's great to talk to you today.

[Federica]: Thank you. I would like to use this, to have the time during this hour to cover many aspects of the decades-long career that you have now, because everything you do revolves around sound and audio, but it's really many different expertise you have. So I read in your bio that, well, you were born and raised in New York City, and that you bought your first tape recorder in early 1963. From then on, you have done a number of things which you will tell us about, but how about we jump to today? We're speaking on Skype over the internet. I would like to use the next hour to go through what has changed from 1963 to today technologically and also otherwise, like the human activities around the technology and what has happened the recordings, you know, the facilities, the music.

[Richard]: Oh, absolutely it's a different world, and I can't imagine going back, to be honest with you. Just to jump ahead briefly, I did a lot of serious classical liturgical music recording in the '70s (which we'll get back to), but there I was struggling and fighting, and I'm still fighting today, with some of the analog techniques which we used, and now it's so easy to, for a lot less money and about 3 pounds in your backpack, you can have an 8-channel digital field recorder that's better than tons well, not tons, but a lot of equipment that we would have to bring around. So it's really convenient. The quality has improved. The accessibility has improved. And of course, the internet has given us fantastic opportunities like this one. Can you imagine in the old days in 1963, we'd probably have to reserve a transatlantic telephone circuit, have horrible phone quality, and then have to pay through the nose for that? So I think it's great where we are, and I would not want to go back.

[Federica]: Would you say then that from 1963 to today, it's out of any question that there has been positive progress, it's better now (audiowise, of course)?

[Richard]: Yes, we don't want to get into politics, because I think it's bad then and bad now, and good then and good now. That's too complicated. But yes, audiowise and I'd like to be a little broader because my life also has involved photography and video and every which way. All media is better. Even books. You could have the paper copy surrounding you, or you could look at it on your phone.

[Federica]: So we're still in kind of 1963. How does it evolve from there?

[Richard]: I was very pleased that, looking back on it, I had a lot of great opportunities as a young child. My father gave me a crystal radio set because he remembers building those as a boy (which, at that point, was the only way you could listen to radio). We put that together. We used to do what's called a broadcast band DXing listening to distant stations together. I had a neighbor who was a professional photographer and an audio/electronics expert (at least he seemed that way to me), and I got to spend lots of time in his basement because my father didn't really have a lot of expertise in it, and I was curious. So anyway, one of the first things I wanted was a tape recorder because I enjoyed beautiful music and I thought it was a shame that some of the music I was hearing in the community wasn't being recorded. So I bought probably the wrong machine, but I didn't know any better at the time, and I made recordings at school and around, and some of them have been useful, like my high school graduation has been entered into the school's archives. When I went to university, I thought I might want to go into electronics engineering, and then I discovered the math load of it was oppressive, and I went back and got a communications degree which focused on broadcasting. And being in New York City, we had professors who talked about what they did at work because they were working for ABC and [NBC 00:04:55] and the major U.S. networks, and we had some of our high-level classes were actually in the offices of the networks with the person. So I had a very fortunate ability to get involved with working summers at ABC, and at that same time while I was in university, at the end of university, I was upgrading my audio equipment and skills and we recorded some concerts that were broadcast on television local television, but still television. Went out and did some fundraising events in the community where I did audio, and once in a while even video camera work, but not much. And then I started doing audio recording of the Great Neck Symphony Orchestra on Long Island, and that really required an upgrade in my equipment and skills, although the orchestra I think has since folded. It's certainly a good place to cut my teeth, but then I got a job full-time at ABC Television New York as an audio/video systems engineer which meant, you know all those wires in a broadcast facility? Well, someone has to figure out where all those wires go and why they should go where they go.

[Federica]: How old were you then?

[Richard]: I just graduated university. I was 23, I guess.

[Federica]: And so far, it was mainly, the recordings you have made, live recordings, field recordings, not much studio recording, or both?

[Richard] No, I don't have the patience for studio recording. I don't want to hear an artist take the same take 22 times. It drives me around the bend. I just don't like that.

[Federica]: Fair enough. Another small question as we go: Was the degradation of carrier tapes in this case already a concern then, or not at all? Like they were fine.

[Richard]: Well, there was sort of a sense that, 'I've got it on tape, so I've got it as long as I keep it away from a magnet.' And I don't think we thought much about degradation because in the U.S., commercial tape recording was born in pretty much 1947, and we're talking about 1975, so this is, you know, 20-odd years, maybe 30, but the early tapes survived quite well, and we didn't seem to have much problem playing the early tapes. And in fact, I still don't have much problem playing many of the tapes from the '40s and '50s. It's the later tapes that have become more of a problem. Jumping ahead a bit, I would say in the '90s, tape restoration of the things that I had recorded that were important to me and I think important to the community became a concern and that's when I started learning about it, but I think that's jumping ahead. So in the '70s I was fortunate to start attending a large and prosperous church, Saint Thomas Church on Fifth Avenue in New York City, and they have the last remaining boy choir in North America where they, it's actually a residential school where the trebles (the boys who sing the high notes) are trained musically and educationally, so it's a full school plus the music education that they get. And they have this choir that performs at services, performs concerts. The men are all paid, so it's a very professional organization, and they've just rebuilt the organ again there, but the organ, when I was there, had about 10,000 pipes in the front organ and about 4,000 in the back organ, so I mean, it was a fairly large installation. And I got involved with a donor who had moved to Florida who wanted to hear better recordings than they were getting, so he paid for installation a permanent recording system, and then we used that for some, supplemented by [my 00:08:44] equipment, we used that to record, I guess, about six albums that were released commercially well, semi-commercially. You could buy it at the church, you could buy it mail-order, that kind of thing. But we sold a couple of thousand [unclear 00:08:56] I think. I wasn't involved in selling most of them. Sold a thousand or so of albums I released on my [own 00:09:04] label. And that was my first exposure to really high-end quality music where it was really, really well performed. And it was a [joy 00:09:13] to me and was one of the things that kept me saying, I joked that doing these recordings were kind of to atone for working on soap operas during the day, because at ABC, one of the big things they made in New York was soap operas. Every day you had actors in a studio doing live to tape. They stopped doing it live, but would put a new episode in the can every day. And that's a production environment with a lot of pressure, so if something didn't work, they have a frontline maintenance department, I was in the system engineering department, but there's a systems problem, you have to go and try to fix it right away. So anyway, I ended up being one of the two lead engineers on building the new studio center for the local WABC-TV station in New York, and in doing that I [put a lot of 00:10:03] equipment from McCurdy Radio in Toronto and got to know the people there, and we were thinking that there were some good things we could do to advance the art of audio. And so in '81, I left ABC Television, moved from New York City to Toronto (which I had grown to love during many visits there), and got to work there. Unfortunately, the capitalisation wasn't quite what I was used to at ABC, and it was difficult to advance at the speed that we wanted to because there wasn't the capital to do that. And actually in '83, the [old man 00:10:35] McCurdy, I say it fondly, who owned the company decided to sell it for reasons unrelated directly to our work at McCurdy Radio, but some peripheral companies created some issues that he didn't want to deal with and just wanted to get out. So I was left looking for a new job, and my colleague who, at ABC, he and two of his friends had formed National TeleConsultants in Glendale, California, which has situated itself for three decades as the premier broadcast or one of the premier, at least broadcast systems designer installer in the United States. So they wanted me out there. My colleague who had done the video for the WABC-TV side as I did the audio in the intercom, he said, 'We want to hire you, because I don't want to think about audio anymore. We need someone who can think about audio.' So for 21 years, I designed a whole bunch of television facilities, the audio side, also got into a bit of working with architects to do the space plan so that the workflow was both compliant with the accessibility laws and the workflow worked for doing the production.

[Federica]: Did you keep recording during those years? Because this sounds like a job that doesn't necessarily involve you, then, with sound yourself. You designed stuff that other people will use.

[Richard]: Correct. I did only minimal recording at that point. Once we moved to California, I pretty much pulled back from doing that recording, on-location recording, partially because there were a lot of people there doing it and I didn't have time. It was 70-hour weeks doing the consulting work, and by that time, I was married and so that fell by the wayside, but I still had, I kept this archive of tapes, and audio didn't fall by the wayside, just my personal hands-on involvement with it. And we worked with George Augspurger quite frequently and also Charles Salter and Associates in San Francisco as acoustical consultants on control room so that we made sure that the control room sounded good so the audio operators could properly monitor the sound that they were mixing. So I was still heavily involved with audio, but just not hands on personally.

[Federica]: Did you bring your tapes to California, your personal archive, or did it stay in New York?

[Richard]: Oh, no, it moved to Toronto, it moved to New York, it moved back to Toronto.

[Federica]: How large, if I may ask, is your personal collection?

[Richard]: In 2004, after 21 years at National TeleConsultants, I decided to go into tape restoration full-time, and our family filled a 50-foot moving van with stuff, and there were 600 boxes, all told, plus all the furniture.

[Federica]: So I wasn't around in those years, and I'm so curious to ask: As a boy, when you had this recorder, after making a recording, the tape was virtually used up. That means if you wanted to keep the recording, you needed another tape. So what did you do? Did you just go to the store and buy a new one? Were they cheap, were they expensive, and were you aware of brand and models back then?

[Richard]: Well, in '63, I used any tape I could get cheap, and I regret some of them, but some have held up okay and some need baking, but that was a little bit later. Some of the cheapest tapes are the ones that I mean, even at the time, they would clog your heads, so you'd buy cheap tape a dollar a reel and find out that it's not that good. You could maybe take it back and say, 'This is junk,' and whatever. But one of the brands we saw a lot of was called Shamrock, and I didn't learn until the '90s that Shamrock was Ampex tape, which later became Quantegy, but it was Ampex tape that had been rejected to put the Ampex name on, but they spooled it onto cheap reels and cheap boxes and labeled it Shamrock, which of course kept up the Celtic theme of Scotch Shamrock Irish tape actually before Ampex bought Orradio, Mr. Orr had Irish brand tape, so obviously they were playing off the Scotch Celtic logo and trying to create market confusion. You know, 'Oh, Scotch tape, oh, Irish tape, which I buy? Oh, well, maybe it's Irish, maybe it's Scotch.' You know. So instead of saying 'Sammy's tape', they chose Irish, and then... I don't know if Orr started the Shamrock before Ampex bought it or if that was under the Ampex regime, but Shamrock was the low end and then actually Scotch was selling melody tape for a while which was the same thing, except Scotch, when they had to put when the Federal Trade Commission said all products have to say where they were made, Scotch just stopped selling melody tape because they did not want to own up to it. They didn't want to even say St. Paul, Minnesota, on it because then it would be obvious, but Ampex just, or Shamrock tape... I don't It just said 'Made in USA', I think, so they got away. I mean, I never tied it into being Ampex tape. I mean, I thought it might be from looking at it, but, you know, there was nothing, there was no web to search, no, nothing to do those days. So the web actually helps hold people's feet to the fire a bit.

[Federica]: So in the '90s, late '90s, you're in California, and how do you begin being interested in tape restoration while you're doing the other full-time job and the family? Because the moment you decide to go back to Canada, you were already determined to start your own business restoring audio tapes, so there must have been a little bit of a building period before then. How did it start?

[Richard]: Well, I started restoring my own tapes, and by that time Mary Beth and I were going to folk music concerts and talking to some of the people and say, 'You know, I'm restoring my own tape.' 'Oh, we've got an old tape.' And it just started word-of-mouth in the folk music community, and I ended up getting to know some Canadian folkies through a variety of introductions and ended up back in It was classical/ecclesiastical music. In the '70s I released on LP, and in 2000 I released some, I re-released some folk music CDs that Mary Beth and I sold out of Glendale, even though it was a Canadian artist. And I recall the National Library of Canada sending me a note, 'You know, you have to send us the legal deposit copies.' I said, 'Well, it's made in the U.S.' 'I don't care. We don't care. It's a Canadian artist. You need to send us two copies.' So they were following me. So it built to a business, and I wasn't making as much at that as my day job, but it was bringing in some money. And 21 years was a long time to be working at the same place and doing the same type of thing, and things were starting to move faster and faster, and more computers, and there were younger people who knew a lot more of the new stuff, and I was having a little bit of trouble keeping up although I've caught up now to some extent but I wanted something where I could, didn't have to travel as much. And I was already being asked to speak at conferences while I was at National TeleConsultants, and I did some restoration consulting projects under the National TeleConsultants banner because people were interested, but they were smaller projects which were, you know, that just took a few days to do, but that point, I decided to talk it over with my wife and then the kids, and Because we had been traveling up here to Mary Beth's family every Christmas, and I figured if I'm going to start my own business, what better place to do it than where the healthcare is paid for, I don't have to meet the healthcare insurance on a monthly basis? So we decided to move back to Mary Beth's hometown, which Now, that was in 2004 with the 600 boxes. And we're still here.

[Federica]: Were the problems that your tapes had the same as the tapes of the first people that start sharing their tapes with you, and were they the same problems that we deal with today? For example, stickiness.

[Richard]: It absolutely was. I started noticing that, actually, in the '80s even, where some tapes would squeal, and at that point I did a very rudimentary version on what's become known as Marie O'Connell's wet playback system, and she's taken that farther than I think anyone else has. And I used the same material, which is basically alcohol as a fast-evaporating temporary lubricant so the tape wouldn't squeal, but it turned out that the tapes that I had were Ampex, and I was seeing the beginning of the horrible sticky-shed syndrome, which is a failure mode where some combination of the magnetic coat which holds the magnetic record and the back coating interact or something (we're still arguing about the chemistry of exactly what happens), and we've learned that we can bake those tapes so that they can be rendered playable for a short period of time. By 'short', I mean weeks, maybe a month and then they start reverting back to their sticky condition, and it depends, but in general you can get a good copy from them. And I will confess, the first tapes I baked I baked in my kitchen oven, electric oven, and it worked, but I think I baked them too hot, but it didn't take so long. We're now more cautious and bake them in food dehydrators.

[Federica]: So back then when you were finding these first sticky tapes, was sticky-shed syndrome already a thing? Were you calling it that?

[Richard]: I think we noticed it for a decade before it started to become a meme, so to speak, in the community where people were thinking the same thing, and I still think there are people who are not totally clear on the definition of it.

[Federica]: And where did you get the knowledge for counteraction back then? I mean, it's not that you could just go on Google like we do today for everything. Or could you? What year was that, late '90s?

[Richard]: Yes, but I think the internet was certainly around, but don't forget, I was in Los Angeles area Glendale's a suburb [of Los 00:21:15] Angeles, and there are lots of audio geeks there. But even as late 2002, 2003, people were saying, 'Ah, I couldn't play that tape, so we just tossed it.' And in fact, it was That mindset or meme was scary in the sense that good stuff was being disposed of because they could not play the tape. So I had Jim Wheeler (who's since passed) who worked for Ampex, designed some of the early helical video tape recorders and also unstuck the instrumentation tape in one of the early space probes when it was out by Jupiter. The tape had welded to the [ruby guides 00:22:01] in the vacuum of space and he managed to get it unstuck without breaking the tape. So we have him to thank for some of those images of perhaps Saturn that we, the first images of Saturn we saw. But anyway, Jim was a real tape expert and a recorder expert, and I think he was very happy that he found someone younger than he to be interested in it, and he spent a lot of time mentoring me. And I brought him out to the Audio Engineering Society. I was vice-chair of the Los Angeles section at the time, and one of the things the board members are responsible for is setting up a meeting every month, so it rotates around, and so when my month came, I said, 'Well, how about I bring Jim Wheeler down from Pacifica, California, and he can talk about some of his experiences? But we really want to say, just because you can't play the tape doesn't mean it's trash.' That was the title of the presentation that I asked Jim to make.

[Federica]: And how did it go?

[Richard]: The meeting went very well. Everyone loved Jim. How can you not? He was a great, great presenter. I don't have any statistics about how many tapes were saved because of it, but the conversation was started, and I got to speak then at a lot of different conferences around, well, from Texas to California, I guess. I went on a road show a bit that probably spoke about eight or nine places, and one of the things we discovered at one place was their archives, the bureaucracy, funding bureaucracy, insisted that they use economizer cycles. They were driving the humidity up to 80, 85, 90 percent overnight, bringing in cold, moist air, and you could see the diurnal cycles of humidity, night high, during the day low, and the air conditioning was working with the normal Freon chillers. But we discovered in that archive that the mag coats were flaking off and you would, when you threaded the tape, that was enough physical stress to the tape to have the mag coat drop off at room temperature. So basically we had tapes with clear leader that wasn't spliced on. It was the raw base film that had lost its magnetic coating, and so you could just It was just a clear leader, but I've never seen a group of tapes that experienced that before, and the interesting thing was, the tapes themselves were bought by purchasing years and years ago, and they were bought from the lowest bidder, and they came in white boxes that didn't even have the, that didn't say Scotch, Ampex, BASF or whatever else. I mean, at least if you're buying name brand, you hope you're getting something good. With white box, you don't know what it is. But we found out actually, when I brought one of the tapes back to my much-better-controlled-humidity home in Glendale, the tape, over a four-month period, healed itself and wasn't shedding its mag coat when I stressed the base film.

[Federica]: I think it's about time to mention how we met, because we haven't known each other for very long, at least in person. In fact, I've been quoting your work in my research papers for a few years now, and so we met in June at a conference, and I was thrilled to meet my literature in flesh and bones. Do you want to say what, where were we?

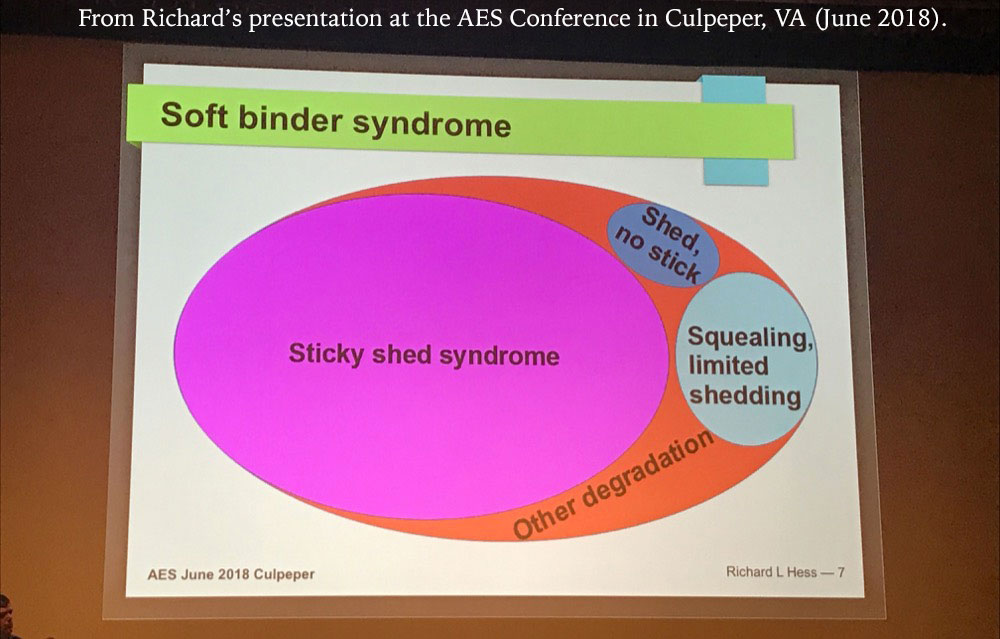

[Richard]: Yeah, well, it was an audio archiving conference sponsored by the Audio Engineering Society, which is an international society anyone interested in audio should really look at it. We had the great fortune of having this conference on archiving hosted at the United States Library of Congress National Audio-Video Conservation Center, the Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia, which is a world-class media film audio-video storage and digitization facility.

[Federica]: Packed with interesting people.

[Richard]: Should I talk briefly about my elephant?

[Federica]: Yes, tell us about your elephant, and also explain the reference, please.

[Richard]: Yes. I had an elephant in one of my PowerPoint slides at the conference, and I said, 'I really need several, because there are lots of elephants in the room. We talk about, we could look at a tape and we can do all sorts of gas chromatograph, mass spectrometry, FTIR tests,' all those things, Federica, that you know better than I what they do, 'and they can tell us a lot about the tape, but there are some things we just don't know.' We start out with not knowing the original formulations, because those were always trade secrets, and most of that information is now lost. Then we don't know about three, at least three types of variations. We have batch-to-batch variations that kind of happened accidentally. We have running changes where [unclear 00:27:09] is tweaked, and we have We're starting to see that there are country-to-country variations in the sense that one particular 3M tape that was made for the Japan market is showing a different type of degradation than the same type number tape that was made for the North American market.

[Federica]: Oh, yeah, and that might be due to the formulation of the tape that was manufactured in that specific place, but there's something I was going to say about modes of degradation of tapes, that also geographical factors should be a little bit taken in consideration because the exposure to humidity, heat, salt, is not the same, and other factors. It's just not the same across the world. And I'm only an expert for the types of tapes I've handled, like I touched with my hands and treated, and it's something very interesting at the conference, but something that should happen also at large by, you know, a platform for sharing information in the community would be that you get in touch with cases that don't belong to your world zone, and so indeed tape degrades in different ways, also, accordingly to where they are geographically.

[Richard]: Yes, and the other thing we don't know, as you pointed out, is the storage conditions and even what their effect is.

[Federica]: And not that they don't travel. Like just you, you took hundreds of tapes from New York State to California to Ontario, so not that tapes don't travel, but it's a factor just because we needed some complication to be added to the mystery, right?

[Richard]: Now, the environment, including the local water supply, seems to have a big, be a big factor in tape manufacturing. For example, Ric Bradshaw, who worked at IBM for many years, and he was the head of the chemistry department at IBM tape development, and matter of fact, he had Bharat Bhushan work for him, who subsequently went to Ohio University, but Bhushan, after he left IBM, compiled two fantastic books on tape tribology, which I recommend to anyone wanting to do a deep dive. But anyway, Bradshaw, originally IBM was making tapes in the Denver, Colorado, Colorado Springs area, somewheres in that technology park area, and they decided to move to Tucson, Arizona, and it took him a year to get the tape line back running making reliable tapes. And I just learned that I knew that Ampex did their tape development in Redwood City, California, but the factory was in Opelika, Alabama, but I just learned recently from my friend Don Ososke, who worked in the Standard Tape Lab in tape testing, that they had a devil's of a time having the formulas concocted in Redwood City work in Opelika because of the difference of the water. So the fact that the engineers were developing a tape that they thought would work, they had problems. So we don't know if that's a root cause of some of the Ampex tape problems or not, but it just There are so many unknowables that we just have to figure out how we can look at the tapes as they are today and do our best to preserve them and get them ready to be digitized, because reality is, we can't conserve all the tapes and the machines to play them into the indefinite future. We can save the content as digital files and move that reliably into the future.

[Federica]: When you were restoring your first tapes, were you then digitizing them? Was that already like the answer, or you were also making another analog copy, for example?

[Richard]: Well, in the early 2000s I had clients who did want me to make other analog copies, and I did for one project and later on was criticized for doing that because that was a waste of money, but that was what the client wanted, you know, and it was a lot of work, and I got paid for it, but still, I would say, starting in 1999, we were looking at digitization as the way forward.

[Federica]: Mm-hmm. I just have to ask, but shortly, how much are you concerned with digital preservation? Concerned by, sorry, worried by the fact that 'Now I have it on digital storage device, so I got it,' like you said for tapes. Do we, do we not?

[Richard]: That's a whole podcast in itself, but the

[Federica]: Yeah, right, okay.

[Richard]: I'll try to do one minute. The first thing that we have in the digital world is, we have tests that we can run, or fixity, which show whether or not the file has changed over time. Message digests and checksums go a long way to helping us with that so we know if the file has changed. You don't know if something's changed in an analog tape. Secondly, if you have an analog tape and you make an analog copy, that copy is not going to be an exact clone of the original, whereas with the digital copy, you could make multiple copies that are exactly identical, bit for bit, with the original. So you don't have a master and a safety copy in two different areas. You have two master copies in the two [different 00:32:53] areas. Personally, all the photos I want to keep currently are on two RAID 6 network attached storage appliances in my house, and one of those, via a circuitous route, is backed up to a service called Backblaze, which is a cloud backup facility. And I currently have almost 9 terabytes in Backblaze and about 11 terabytes on my backup server and over 12 on my main server. There are things I don't care if I lose, but it's convenient not to have to go look for them again on the web if I don't have to.

[Federica]: Mm-hmm. So what motivated you to start your own website with the information about tape restoration which is now a go-to place for the worldwide community and that was brought up several times at the conference? It's truly an important reference for the community not having [unclear 00:33:52] today still this knowledge base or official, you know, shared institutionally based, possibly, repository of information. Your personal website or blog however you, I don't know, you see it, you call it is one of the main references worldwide. What motivated you to start accumulating [information 00:34:20] in your website instead of keep, you know, sharing links with your circles and so on, and when did you realize that the website was attracting so much attention?

[Richard]: Well, I'm going to be slightly crass about it. I started it for marketing purposes as I was moving into this, because my thought was that if [unclear 00:34:52] this stuff, there are other people out there who don't know this stuff, let's collect it. And I actually linked to other people who could do some of the same work or extended work as well as me, because I figured from day one, 'I'm not going to be able to cover all the tapes there's just too many of them but let's get this stuff [restored 00:35:11].' So I think I was talking another restorer yesterday, and we were commiserating with each other that we felt a need to help people who needed to get their tapes restored, and neither of us were readily available to help him, but I thought he might have a machine, but he'd already sold it, that might have helped this person. It was a very messy thing, but we both felt a need to try and help this person. So there is a societal conscience in those of us, I think, who do this and I started realizing that there was a lot of misinformation out there, and I thought I'd start publishing what I considered to be less misinformed, the best that I could put up. And that grew and grew, and I had people in the middle years of the construction of that offer to do guest articles for me. There are a couple of good ones up there, including, I think, one by Jim Wheeler. When I started looking into this in 2005, 2006, tape degradation for the paper that [unclear 00:36:15] published in the [unclear 00:36:16] Journal in 2008, tape degradation factors and something about life challenges in predicting tape life or something like that. It's on my website, richardhess.com/notes gets you to the blog. The blog is an outcome of my not really enjoying doing HTML coding, so turning it into a WordPress blog, it was much easier to create new pages and link and edit, so it is a WordPress blog, and I also have I have static pages there and notes, and I've just recently rearranged it with a more contemporary theme, and there's less of a difference now between static pages and blog posts, but they're all searchable. There are different ways, a couple of different tree paths in the new menu. There's a quick reference what I think people need the most, but then there's some more detailed things you can drill down and see all the variations. I tried to list on that website just about every audio format I was aware of. I have to say that I run a few other websites, and my own website is getting an order of magnitude more hits than any of the other websites that I host. So I haven't honestly looked at what page, but let me tell you a little story I have a page on here that says, 'I don't think we're going to see software decoders for noise reduction systems such as Dolby and dbx, because, personally, I've been asking Dolby for 20 years to make one,' and so someone wrote me. He said, 'You know, I found over on this other discussion board a guy in Indianapolis named John, John Dyson, who is working on making a software decoder that is compatible with tapes made with the Dolby A process, and why don't you two meet each other?' And we did in February of this year, and as of the AES conference, I generated a little bit of excitement by saying that we were about ready to release a software decoder that is capable of playing tapes that were recorded by Dolby A encoders. So that was a good deal of excitement, and John and I have been working hard on trying to get 'John and I'. John has been working hard at burning through little glitches that he's heard, and we think at this point that he's addressed He's a very thorough and capable software engineer, and at this point he's addressing items that are improving the performance over what the original analog processors were able to do during the decode by removing distortions. And an interesting aside to show how careful he was, Bob Katz, who wrote a book on mastering, was talking to me about it and he said, 'Can it do a specific function?' And I wrote John and John said, 'Oh, yeah, that's already in there.' So the guy is really good. And he actually wrote much of the FreeBSD, Linux core back in his earlier days working at Bell Labs. So this is something to look forward to as part of a restoration suite that we actually hope to sell, because John's got a lot of effort in it, and he deserves a lot of compensation for that and a lot of effort, but this will eliminate the need for having software decoders for tapes that are recorded with noise reduction systems. We hope to do eight, but that's not a promise.

[Federica]: Just a curiosity. In the late '90s, when you started digitizing tapes, what kind of sampling frequency and bit depth did you use?

[Richard]: Oh, you're going to embarrass me now, Federica. 4416.

[Federica]: Whoa, whoa. No embarrassment there. I mean, I think it was a very popular standard back then.

[Richard]: I mean, remember, when I was first starting this, it was basically so I could listen to the tapes, and the products were all CDs, but I think by 2002, 2003, I had moved to being able to do 9624.

[Federica]: Yeah, I know many other digitization projects of the early 2000s were still using 44.1.

[Richard]: Right, and then I've subsequently moved my lower-quality digitization to the IIS standard of 48.

[Federica]: Yeah.

[Richard]: But I've actually The aforementioned Dietrich Schüller embarrassed me at the JTS Conference in Toronto in 2007. I was part of a panel with Jim Wheeler and John Spencer, and the three of us were each picking a non-digital repository technique to discuss. I mean, that was the purpose of it. And I was given the topic of optical media (DVDs and CDs), Jim Wheeler talked about shrink-wrapping multiple copies of the computer, and John Spencer talked about LTO tape. And Dietrich got up and said to me and Federica, you know how dramatically he talks and he said, 'Oh, but Richard, you, I can't believe you're even suggesting using optical media. It's so last century.'

[Federica]: And eventually?

[Richard]: I, at this conference was the next time I met him 11 years later, and I said, 'Thank you, Dietrich. I don't hold any grudge about that, and I want to thank you that you precipitated my move to actually not even offering on a regular basis optical media to my clients.'

[Federica]: This is Dietrich calling you on the phone, I think.

[Richard]: Oh, your hearing is better than mine. Just ignore that. It's in another room. Dietrich proved me wrong. No, it doesn't, because he, Dietrich No, I said to him that I want to fully bury this hatchet, and I actually thanked him for it because it caused me, earlier than I would have otherwise, to become alert to this bad direction that I was going in, even though I was doing it for good reasons, and in fact, it informed the document that I helped, I co-wrote for the Canadian Conservation Institute which was aimed at these First Nations bands being able to preserve some of their cassettes. And we had a year-long discussion at the Canadian Conservation Institute trying to decide, do we go with optical media, or do we go with multiple hard drives? And the multiple hard drives is what's in the paper, and it's available. If you search my name and 'Canadian Conservation Institute', you can find it. It's now free, freely available. When it was first new, they sold it to get back their investment, but now it's, because it's getting older, it's now free.

[Federica]: Putting all the competences that you embody together is no easy thing at all. Would you have an advice for younger people who want to engage with this type of activity, tape preservation and tape restoration?

[Richard]: It's a difficult question. I have a friend I made about a year Well, I've known her for about 10 years, but we became friends about a year ago, and she asked me to mentor her in tape restoration and I said, 'Okay, can you mentor my son in live sound?' And she said, 'Definitely.' So the good news is that Robert's been doing some live sound gigs in Toronto, and she is still learning, wading through papers and being very busy in her rest of her life and not coming as far along as quickly as I would like, but she's happy with the progress, so I do I have given seminars. I do mentor people. I don't know the answer. The problem is that it's so multidisciplinary in many ways, and actually, to some extent, that's an area that makes people nervous to attempt to get into it because you have to think about chemistry, you have to think about physical properties, you have to know about analog, you have to know about digital, you have to know about digital file storage if you don't want to lose all the stuff you've made, you have to keep either Macs or Windows machines smiling at you, and both of them can be problems from time to time, so it's I don't think there is a program that really teaches this, because the reality is, it's only very few people are needed in this business, you know. I think 20% of the population involved with this was in Culpeper, in a way. There were 200 people there from around the world, and, you know, are there, is that 20% or is it 10% or It's more than 1%.

[Federica]: You say that this is a niche, and indeed it is in a way, but when we talk about tapes and analog recordings, in fact we don't just talk about historical tapes, because they are still being used for creative purposes.

[Richard]: Yes.

[Federica]: So actually, people keep buying new tapes now. All manufacturers are not out of business, and I don't see this profession to go away anytime soon. You know, it's not just the old tapes and we are digitizing them now, so one day we will be done with it, we will be able to say, 'Now we digitized them all and we're safe.' I see this thing going on in the future, and therefore it's important to preserve, you know, to pass down also the knowledge to use it proficiently.

[Richard]: Well, two years ago, at the 50th ARSC Conference, Association of Recorded Sound Collections, in Bloomington, Indiana, at Indiana University, Kevin Bradley of the National Library of Australia said, 'Well, 20-odd years ago, I came here talking about our program to digitize our audio tape holdings, and I've come here this time to essentially say we're done.' So he feels that Well, there's still some work to be done. They're essentially through their main collection and have it all digitized.

[Federica]: This brings up the question of the parallel digitization as opposed to one on one. Both approaches have advantages and limitations. They, of course, differ in the time it takes to get the job done, the cost, and the resources in general, including equipment and personnel. What is your experience with it, and what is your standard approach in your practice?

[Richard]: Well, actually, I have been one of the proponents of parallel digitization with care, and in fact, Mike Casey from Indiana University visited me to talk about that. And what I discovered was, I was getting a lot of oral history cassettes in, so I would set up four machines and play four tapes simultaneously. I have a 5.1 surround system in my studio. I would root each tape machine to a speaker so I actually [had 00:48:34] full-time monitoring of the quality of each tape to see if there were any problems.

[Federica]: So you switch from one monitor to the other?

[Richard]: Yes. Typically, if I'm doing that, tapes probably on average would be C90s, so it [unclear 00:48:50] an hour and a half, and with this, it's an hour and a half in the morning and an hour and a half in the afternoon. I can't stand doing two sessions in morning or afternoon. But still, that gives me 12 hours of digitisation in 6 hour in 3 hours of [unclear 00:49:05]. So that, I'm in favor of. It all really depends on what you have I think. The largest purpose-built facility for mass ingest in North America is what Indiana University has done, [unclear 00:49:20] Casey and his team there have done a wonderful job, first of all, selling the university the need to do this and [do it all at once 00:49:29] to get the economy of scale. Then they built up a workflow where they have a contractor who came in and built a system and run the mass digitization. And I know that there are people who have problems with the way that they wash discs, but it's also a lot better than not washing them, and I don't think they've lost many, but what they have in the workflow is a bifurcated forked workflow. They bring over a carton of tapes, they've gone through The individual units have gone through the tapes and discs and rated them through the They changed the name, but it was originally called FACET, which was a very complex and detailed way of looking at the quality, examining the tape quality and problems so that they would kind of know the problem they had going in. And so the ones that are already horrible problems are kicked out to workflow B, let's call it, and they don't even see workflow A, but if workflow A runs into a problem, they have fixed prices that they have to do each tape for, so if they have a problem, they don't have a budget to go after it, so that tape is then kicked out to workflow B. And workflow B is a couple of rooms where transfers are done one on one by a dedicated engineer for each transfer, and those are run by the university, not the contractor. And I think this is the best model I've seen of how you deal with this, because I know it when I'm doing four cassettes at a time, one or two runs on a project, I'll have tapes that I throw out of that run and just abort that one tape and keep the other three going because it's too problematic and I have to spend time with it. And I should say that the problems are not always something you could look up in a script. They come and surprise you. 'Why is the tape doing that? Why [am I 00:51:38] having this effect? I don't understand it.' And at that point, you really need to spend a lot of time and step back and stop playing the tape and try to figure out what's happening. One that comes to mind is some Canadian-made C120 cassettes, and C120 cassettes are known to be horrible to begin with. These make the normal ones look good. They have a warp in the base film, we believe, that causes them to not lay down one layer on top of the other, but rather they skew so that you actually have a very shallow cone of tape on the hub rather than a flat pancake. It's like a cupcake kind of thing, but not quite as, not nearly as pronounced, or where you would put a tart together, like a [fruit tart 00:52:30]. You see, you have this cone that ultimately the outer edge hits one side of the shell, and the inner edge by the hub is hitting the other side of the shell and the tape binds. And so far, the only thing that I found that I could do is, I actually loosened the screws in the shell so that there's more room in shell and that's I get through one of those tapes sometimes, but that's a That's not in the books, and it's not something that is easily duplicated, because I think I've seen about a half dozen tapes, they were all the same brand, and they all did it.

[Federica]: The problems in the workflow are actually something used to excite me quite a bit. I used to say that I'm a tapes doctor, but an evil doctor, because when I find a tape that has a problem, I get excited because it's an opportunity to learn something new, I mean a problem that I have not seen before, and the worse the problem, the happier I would be. 'So let's stop the workflow and let's start researching what this problem might be and what we can do about it.'

[Richard]: Or at least kick it out of the workflow to look into it, because you still have to get your quota of tapes digitized, and that, as a sole practitioner, I find, is the challenge. I, too, enjoy the challenge of solving an unknown problem and getting the tape transferred, so I tend to spend inordinate amounts of time on a tape like that, and then I'm not getting the other work done that is easy to do.

[Federica]: With your experience, do you still learn today? And by that, I mean do you still encounter tapes that show problems that pose a challenge for you? Or mostly, you know, you've seen everything, you know how to deal with most tapes?

[Richard]: Good question. I think I'm becoming more sensitive to certain types of errors. I don't know if they're becoming more prevalent or if I'm just becoming sensitized to them. Just received a Dolby B cassette tape which wasn't marked Dolby B (which created its own set of problems) that was poorly recorded, and it was of a wedding at Salisbury Cathedral in England. It's quite a nice ceremony, and the people are friends of mine and would like to have it saved, but So there were a lot of issues of trying to figure out a better way of aligning the playback system to play back the Dolby. I still find that to be a challenge. There's a lot of art to that. I've had lots of discussions with Tim Gillett in Australia, who is a proponent of re-equalizing the tape before you try the Dolby decoding to try to make it flat, as well as adjusting the level. So those types of challenges, refining techniques, still come up. There are just things that still can't be fixed, like that tape has overload, especially at the low end on the pipe organ, and even the best declipping algorithm still could be better. We just don't There just may be things that can't be fixed, but we keep trying to push the limits of bad tapes to get the best possible sound off of them.

[Federica]: Have you ever been touched or moved by a tape you were digitizing? And by that I mean something that has definitely happened to me a few times during my intense digitization years, so to speak. I was fortunate enough to receive some very fine archives, and I felt privileged to be the first person to listen to that audio, sometimes in many decades. Especially, I can remember some live recording, some folk music, rehearsals or some person telling about their own life many, many years ago in the countryside in Italy. It really stayed with me. I felt so touched that I thought then if more people could understand what kind of asset we have in these tapes not all of them, of course, but we need to find out; we need to curate the archives, precisely, and sometimes digitization is a necessary step to finding out what's in the tapes if more people were aware of this asset, then it would make a difference in the efforts we make to preserve this which is such a large part of our cultural heritage, of our identity, and this is always true, not just in 2018 European Year for Cultural Heritage. This is just always true. So have you had this similar experience? Has some tape brought back to life some sounds that touched you?

[Richard]: In many different ways, many of them. I guess one of the first ones that comes to mind is the late Stan Rogers, who is a Canadian folk icon, produced about five albums and he died in '80 or in the early '80s in an airplane crash in Cincinnati Airport where the plane caught on fire in midair and he didn't make it out. Some, many people did, but he did not. And his producer, who's a repeat client of mine, Paul Mills, brought me the album, said, 'We really want high-resolution transfers of these done, and we're going to re-release them on CDs.' And his last album, From Fresh Water, I just thrilled to hear the transfer of that again and again. It's just a beautiful, beautiful album. It has been remastered, and it's been remastered more for today's ears, and I like it both ways. I like the way it was originally mastered in the '80s and the way it was remastered by João Carvalho to be more in keeping with today's sound. That was just a beautiful album. But some of the other things, I've done 100 reels or 120 reels of Arab folk music was, were field recordings, and these tribes in the Gulf states, recorded in, I think, the '70s as things were really changing in that area, but these were still people who were around old cities and even some nomadic people, and it was their singing and their talking. And I couldn't understand a word of it, but it's that kind of history. And I've done First Nations tapes that you wonder how many people speak that language that's on that tape. So all of this is, I find very moving and very important to keep.

[Federica]: Wrapping up this incredible conversation, I think we really have to send our thanks to the key people that made the Audio Engineering Society Conference possible last June in Culpeper because had we not met there, this podcast episode would not be happening. So thanks to John Krivit, Nadja Wallaszkovits, David Ackerman, Brad McCoy, and of course, our greetings also to Dietrich Schüller, who was there, and so many other amazing people we met there. I understand that you'll be contributing to the next conference in New York very soon in October.

[Richard]: I am. I will be at the AES Conference, probably talk about the software noise reduction decoders.

[Federica]: Since we have a common interest in furthering the knowledge in this field and we need tapes to actually do more chemical analysis and tests, I think we could just invite our audience to send us the tapes they don't use anymore. First of all, of course, just don't throw them away. Even if you don't give them to us, please don't throw tapes away, but if you really don't know where to put them anymore, well, do look for the contacts in the description of this episode or go to technoculture-podcast.com, get in touch with us. We will make good use of the tapes and keep you up to date. And by the way, we would only need 30, 20 centimetres of tape at the bare minimum, so don't worry about shipping boxes. There is really a way to do this, so do get in touch. You know, we should start a campaign that's called Donate Your Tapes for Science or something.

[Richard]: I think we're very interested in seeing tapes that are suffering from sticky-shed syndrome, which is not, which are in advanced stages that have never been baked.

[Federica]: Okay, so donate your tapes for science. Thank you so much, Richard. It's been a pleasure to talk about this topic that's so dear to my heart with such experts as you are.

[Richard]: Well, thank you, Federica. It's always a pleasure with another great expert. I've found you to be very much a kindred spirit in trying to keep tapes alive.

[Federica]: Thank you so much. Thank you for listening to Technoculture. Check out more episodes at technoculture-podcast.com, or visit our Facebook page @technoculturepodcast and our Twitter account, hashtag Technoculturepodcast.

Page created: November 2018

Update: July 2021