The audio engineer of books: It helps not to know him well

with Richard RomanielloDownload this episode in mp3 (37.84 MB).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The first thing that I ever did with (or rather to...) Richard Romaniello is shouting his surname in his face. We were at the AES Convention at the Packard Campus of the Library of Congress in Culpeper, VA, in June 2018, and we didn't know each other. I read his name on the tag and went full ROMANIELLO! Turns out, he is Italian by descent but he doesn't speak much Italian as he's a 100% New Yorker. And the second thing I learnt about him is that he is an audio engineer of audiobooks. Isn't that an interesting sector? Audiobooks! So I decided to learn more and what better way than to invite him on Technoculture, and oh the stories he had to tell.

A few days after the conference last year, I visited Richard at his workplace downtown NY, the Penguin Random House Audio, the largest commercial publisher on the planet with over 200 audiobooks releases per year. He showed me around the studios and told me about the specific challenges of engineering an audiobook. If it sounds easier than music, you're wrong. It's a very specific craft, and Richard is a master in the field.

This is what he says about himself:

"I have been playing with tape recorders since 1965 when I got my first tape recorder for my 10th birthday. The brand was Acme and I got 3, 3" reels of Shamrock tape (which later became AMPEX tape). I made ambient back round tapes of bombs falling and machine gun fire for my G.I. Joe dolls.

A few years later my family got a reel to reel so we could exchange audio letters with my cousin in Nevada. I didn't get any formal education in Audio until 1981 when I attended The Institute of Audio Research in NYC.

I believe it was the first school for Audio Engineers in the country. They were established in 1969 and unfortunately closed in December of 2017. I graduated in 1982 and have been working as an Audio Engineer since then. I was very lucky to have met Malcolm Addey (Chief Engineer @ EMI Abbey Road from 1958 - 1968) in 1983 and I have been his protégé since then. I have worked with the greatest Jazz musicians on the music side and with some of the greatest actors on the spoken word side."

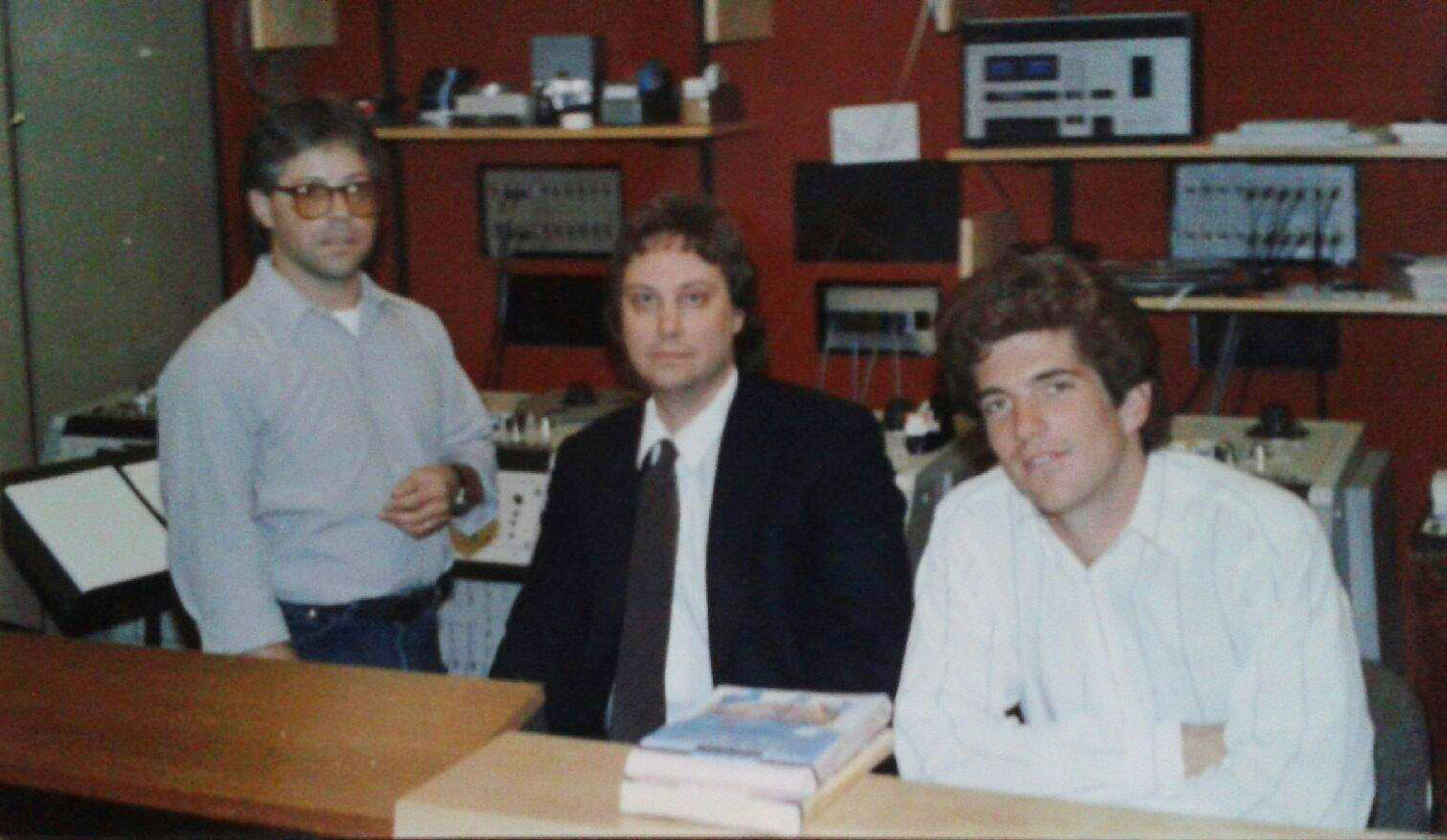

Fig. 1 - Richard Romaniello with producer John Wynn and JFK Jr.

The list of musicians, actors, political figures, and celebrities Richard has worked with, and the titles that were nominated for Grammy Awards is long, but here's a highlight. Spoken word: Glenn Close, Matt Dillon, Michael Douglas, Michael Moore, Dolly Parton, Christopher Plummer, Caroline Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Jr. And for music: Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie, Tom Malone...

Fig. 2 - Can you guess who that blond is? That's right, she's Dolly Parton!

Richard is also a musician and at the end of this episode you can hear a live recording of his band, "The original famous rays", peforming the song "It helps not to know me well". In the slider below: left to right, Kevin Schmidt-Baritone Trombone, Rafik Cezzane-Tenor Saxaphone, David Frawley-Trumpet, Keith Mulhare-Drums, Jim Wilmer-Keyboards, Richard Romaniello-Vocals and Guitar, David Wasserman-Bass and Backing Vocals. The picture was taken in Lincoln Park, Jersey City, NJ on Aug 8th 2018.

Richard is someone who has worked "behind the scenes" all his life. He's not a loud man, you may easily underestimate him. But if you... know him better ;) you get to appreciate the audio professional he is, loving father and husband, hard worker, musician, and black belt of karate. Among other things! And what a kind soul. I think men like him rarely get in the spotlight, but they keep the world moving forward, with their hard work every day... behind the scenes. I am glad I got to hear and share some of Richard's stories in this episode of Technoculture.

Here is a live recording of Mozart's Requiem Richard made a few years ago at St. Patrick's Basilica in Little Italy NYC. He recorded the concert and Malcolm Addey mixed it. And then back to audiobooks! https://vimeo.com/222568804

My favourite quotes from the episode: "I like noise."

And: "I completely got into the business by accident, but I became enamoured with storytelling. This is what a book is: storytelling."

Go to interactive wordcloud (you can choose the number of words and see how many times they occur).

Episode transcript

A list of topics with timed links is available in the description of this episode on YouTube.

Download full transcript in PDF (124.89 kB).

Host: Federica Bressan [Federica]

Guest: Richard Romaniello [Richard]

[Federica]: Welcome to a new episode of Technoculture. I'm your host, Federica Bressan, and today my guest is Richard Romaniello, a Grammy award-winning audio engineer and producer with numerous nominations for engineering and producing audiobooks. Richard works at the Penguin Random House Audio in New York, and has recorded the voices of hundreds of celebrities, including Glenn Close, Michael Douglas, Dolly Parton, Michael Moore, Caroline Kennedy, and John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr. Richard has extensive experience in all phases of audio recording and production, and with multiple genres, the spoken-word as well as music and theatre. Welcome to Technoculture, Richard. Tell us about audiobooks, and how you got involved in this business. Is that correct that you started by accident?

[Richard]: Totally by accident. I was working in 1985 in a little local studio in Rutherford New Jersey and I sent a resume to Bob Katz to assist him on location recording and I never heard back from him. I sent him the resume in March of '85, I didn't hear anything and then August of '85 I get a phone call from him saying, have you ever heard of Cadman Records? I said no, he said have you ever heard of Arabesque Records? I said no, he said well I see that you went to the Institute of Audio Research, I went from September 1981, graduated in September 1982, and that you worked with Malcolm Addie who was the chief engineer at Abbey Road from 1958 to 1968. And I said yes, I have, and he said well I'm gonna call Malcolm and if he gives you a good reference, I'll tell you who to call. So he calls Malcolm and I make the necessary phone calls to talk to the folks at Cadman Records and next thing I know they hired me. So I started in September 9th 1985, I thought I would do it for about six months because I was in the music recording business, and I was there for 24 years, five months and ten days, or something like that, and was laid off during the economic downturn in 2009. And I freelanced for two and a half years and then in September of 2011, I got hired by Penguin Books to be their in-house recording engineer for their brand-new studio downtown in Soho. And about five years ago or two years into my tenure at Penguin, we merged with Random House and became the largest commercial publisher on the planet. And we here at Penguin Random House, we produce about 1200 audio books a year and they average in length, about 10 to 12 hours, some are much longer and there are a lot that are much shorter, but that it averages out to about 10 to 12 hours. And it takes us three to four days in the studio to record it, it takes somebody about three or four days to edit it and we turn this stuff around in an unbelievable amount of time, it's a very short turnaround time, because we ride the coat-tails of hardcover publishing and marketing. Although, here at Penguin Random House we have our own marketing people, whereas most of the other publishing houses what they do is, the same people who do the marketing for their books also do their audiobook marketing and they're really two very different markets. When I first started in 1985, I worked on about 30 new titles a year and they were an hour to 90 minutes long and we reissued 15 of the Cadman titles from the back catalogue. And just to give you an idea, Cadman Records started in 1952 and their first recording was Dylan Thomas reading, 'A Child's Christmas in Wales', which is probably one of the most famous spoken word recordings of all time, so many people know that. And when I went for my interview, when they showed me an LP, I recognised the label from when I in high school English class when they played records of Shakespeare plays, which Cadman had about 42 of them recorded with British casts in the 1950s and 60s. So long story short, I completely got into the business by accident, just amazing, but I became enamoured with storytelling and that's what an audio book is, it's storytelling, it's the second oldest art form on the planet and the first being cave drawings and then from cave drawings came storytelling around the campfire and it's just an incredibly intimate medium. Some of the stuff I had the luck to record was just so astounding, so wonderful. And one of the most impressive recordings I ever worked on was, we did at Harper Audio - Cadman was bought by Harper Collins - we did the Dubliners series and we had Irish actors reading each one of the stories, a different Irish actor reading. I recorded Ciaran Hinds reading the story, 'A Painful Case', which was a story about requited love, or unrequited love I should say, and his performance was just so incredible and moving it was just unbelievably beautiful. And when he was reading, he had his chin in his hand and he was leaning up against the microphone, very close, speaking softly but we had a really nice Neumann TLM 170 and about 20 minutes in, I realised I could hear his wristwatch ticking and it was a real watch, with a movement, so it ticked about three or four times per second. And his performance was so incredible that we didn't want him to redo it, so I spent about two days editing the first 19 minutes of the recording, editing it down to a finished product, which was about 10 minutes, and I had to cut all the ticks out between the words, or at least the phrases, and at the time we probably were using sonic solutions which had a de-clicking program in the no noise program, but I had to do each one individually, I couldn't do a batch processing, so it took me quite a while to do it. It was like editing analog almost, I had to literally cut out or find every single click and get rid of it, and it paid off because it was just a wonderful sounding recording and I didn't have to have him do it over again and not have that magic and that's the thing - even in music studios - they're always rolling tape because you never know when you're gonna capture the magic, so, that's certainly something to consider.

[Federica]: Thank you for giving this overview of different aspects of what you do, I'm eager to ask you much more about your work, because most audio engineers that I have met work with music, with rock bands or classical music, but it's quite rare to meet someone who specialises in the spoken word. And this audio book is not even a niche anymore, it's actually a huge market and it fascinates me because, like you said, it recuperates a tradition of circulating the spoken word, like a podcast. So I am fascinated by the potential and the potential implications of what this means, of how the web and portable devices make it easier to circulate the spoken word, which is storytelling, even this podcast in a way, it's storytelling. Today it's your story, speaking of storytelling. I want to tell the story of how we met, because it's basically the reason why we're talking today and that is, I was and you were at the Audio Engineering Society conference at the Library of Congress at the Packard Campus in Culpepper, Virginia, where by the way, I also met well a number of incredible people - another guest of this podcast Richard Hess, episode number 10 - so I met a lot of interesting people there and browsing the lobby I noticed this man with an Italian name on his tag and I was so convinced you were Italian, so I just opened my arms and I called you Romaniello, and you responded with a big smile like we've always known each other and you told me, of course, I am of Italian origins but I don't speak Italian, I work with audiobooks and this is how we started talking. Would you like to share what your memory of that moment is?

[Richard]: Sure, I'd be happy to. I approached you in the lobby and in my American Italian way. First of all, I thought your talk at the conference was terrific, I thought you did a fabulous job and I was captivated from the very beginning, I thought you were absolutely terrific, really.

[Federica]: Thank you very much for the kind words, the fascination was indeed mutual, as soon as you said audiobooks, I knew I wanted to know more, you never think about it, audiobooks are just there. But who reads these things? To read well is such an art, is it the author who reads or is it trained people, is it actors, or is it actors that only do this. And I just wanted to know a lot more. To proceed in order, let's go back to the origins, you said that you produced your first audiobooks in the 80s, now the world was a different place then, so how has the world of audiobooks evolved since then?

[Richard]: Yes well, when I first started at Cadman in 1985, my finished product was an LP. I was recording for LP release for long-playing records and also cassettes, we would put out a title on both versions and from there we moved just to cassette only and then once CD replication became cheap enough, we went to all CDs and now it's downloadable. We're almost at the point where we're going to stop putting out CDs, but libraries want physical copies and some people just hold on to technologies, even when they're dying, and I have five reel-to-reels at home, so I know all about dying technology. When I first started, if we sold 750 pieces of something, that was considered the break-even point. Now, we don't even consider recording a title if we don't think we'll sell say 10,000 copies.

[Federica]: And throughout the years, you have recorded hundreds of people among which are celebrities and politicians and actors. I dropped some names when I introduced you at the beginning of this episode, can you drop some more?

[Richard]: Well, I've worked with famous politicians, famous Academy award-winning actors and actresses, or actors, we'll use as a non gender term. So let's see, I've worked with, in terms of politics I've worked with, former Vice President of the United States Dan Quayle, I worked with House Speaker Newt Gingrich, and the former Governor of New Jersey - two former governors of New Jersey Jim McGreevey and Christy Todd Whitman - then in the field of...

[Federica]: JFK Jr.

[Richard]: John F Kennedy Jr., yes I did work with [him] and his sister Caroline, I worked with John F. Kennedy Jr., it was 1988, I was still at Cadman Records and he came in and he read his father's book, 'Profiles and Courage' and he was absolutely a wonderful person. There was no arrogance or attitude of being an entitled person, he was just a regular guy. He, as a matter of fact, he showed up in a t-shirt and shorts and rode his bicycle and he rode without a helmet, and I yelled at him, I said that's just crazy to ride without a helmet, because I'm also or I was an avid cyclist. And I said, you gotta be crazy to ride without a helmet and actually the next time he came he wore a helmet.

[Federica]: You told JFK Jr. to wear a helmet?

[Richard]: I did, I did tell him to wear a helmet. He literally, he came from work, at the time he was an Assistant District Attorney in New York and he came to my place of - we were at 1995 Broadway at the time - and he came there literally, honest on his bike with no helmet, in a t-shirt and a pair of shorts. It was just so unpretentious and he was just, he was so easy to work with, no attitude whatsoever. It was stunning when I heard the news of him dying in the plane crash, and I have a friend who owns his own small plane and I had flown out of the airport that John F Kennedy Jr. took his fateful flight from, on a number of occasions, so every time I go there with my friend, Charlie, we reflect on that, it's kind of neat and tragic at the same time. But yeah, he was very cool and his sister was very gracious as well.

[Federica]: What did she read?

[Richard]: What we did is on the 10th anniversary of our recording of that - now John had died by that time - we re-released it and we had Caroline do an introduction, so she came in and read for, I don't know maybe a half hour or so, and read an introduction and that was incredible. So here it is, I'm kind of touched to the Kennedys in person and we're working on their father's book, so that was pretty amazing, that title was the first of my 13 Grammy nominations. I think it was 1990 when it was actually nominated for the Grammy, but I had no idea there was even a spoken-word category in the Grammys, but there is.

[Federica]: I admit I learned about the existence of many of these awards preparing for this interview, so I see the list of your awards and nominations here, you've been nominated almost every year in the early 1990s and then in the early 2000s. During those years, you always kept recording music on the side, so not just spoken word, and you're a musician yourself - we're gonna talk about that a bit later - we also have a small surprise for the listeners. What I want to ask is, you have experience both with music and the spoken word and when someone says I'm an audio engineer, that sounds like something very generic, so is the way you approach music, any genre, different than the way you approach the spoken word and if so how, what kind of skills are unique to this sector?

[Richard]: Well, it's harder than I thought. My first day on the job at Cadman, the person who hired me, Ward Botsford, he was the executive producer at Cadman for about 20 years and he was a very unusual character. The first thing he said to me, he goes, this is not like recording Bob Springsteen and he was being serious, he didn't know that it was Bruce Springsteen, but what he meant was, you have to capture everything from a whisper to a scream and you can't ride the fader, you cannot pull the fader up and down to accommodate the reader, you've got to be able to set the microphone correctly and be able to capture a whisper or a scream without it being too noisy - because we're still analog at the time - or breaking up, being too hot. And I thought wow, it seems so easy you got one microphone and one mouth, but it's harder than you think because there's nothing to mask any... you know, if you move, you rub your arm or scratch your face, or your leg, you hear that and it takes you completely out of the storytelling mode, especially when it's an audio-only presentation, because when we see each other in person, the brain discriminates and we don't hear the swallows, and the sniffles, and the scratching and that sort of stuff. Our brain, because we're seeing the person as well, knows that those are unimportant things but when we're only listening, those kinds of noises become distractions; we don't hear those as much when we're looking at each other, but when it's audio only those kinds of noises become very off-putting. So, getting someone in the studio to be expressive and like you and I, we're Italians, we talk very much with our hands, we want you to move your hands but we don't want to hear any sound from it. It's really tricky, so it's tricky from the people who are in the booth and it's tricky on the outside because the level of concentration is, it's mind-numbing. Because we do sessions, we start 10 o'clock in the morning we go to around 1:00, break for lunch, there's a few breaks between 10:00 and 1:00, take a bathroom break or just stop for a few minutes and just let your head clear. And then after lunch they come back and they record from, say 2 o'clock to 5 o'clock and then [for] an average book you do that 3, 4 days in a row. I've done audiobooks where we took 10 days like that to record.

[Federica] : I can only imagine how hard it must be for the person in the booth too.

[Richard]: Oh, absolutely.

[Federica]: It's not easy to read that long and keep the quality of the performance, I might imagine that after 2 hours you may slow down, or speed up a little bit just slightly so that you barely notice it. But of course that shouldn't happen, so what are the most common problems in that sense that arise, like speed change?

[Richard]: Well, when I first started, almost all the people that we used were celebrity talent and they weren't necessarily gifted at audiobook reading. As a matter of fact, the term audiobook didn't exist when I started, that term was coined a few years after I was in the business, but it was originally, it was almost all celebrity talent, it was either an author or we did a lot of stuff with Christopher Plummer. And in the 50s, Cadman had Boris Karloff read Rudyard Kipling and I mean, just incredible stuff.

[Federica]: We've already dropped some names, of course, the list of the people you've collaborated with just goes on and on and on and on and there's no shortage of celebrities.

[Richard]: Lucky, lucky me, because like I was saying before, I got into this at a late age compared to most people and happened to hook up with Malcolm Addie and so the musical stuff, those great, the great musicians, the greatest jazz musicians that ever lived, I've worked with. A recording I worked on with Malcolm Addie was recorded at the Town Hall in New York and it was Red Norvo on vibes, Louie Bellson on drums, George Vivier on bass, Benny Carter on alto sax, Remo Palmieri on guitar, Freddie Green on guitar, Pearl Bailey came out and sang a song and, of course, Teddy Wilson on the piano. And it might have been the last recording of Teddy Wilson's ever made, he died shortly after that recording and he was very sick at the time of the recording, and so when they were performing, he only soloed but he pretended like he was comping, but he was in so much pain that he just couldn't do it. And we were set up - the control room was literally downstairs from the stage - so we couldn't really see what was going on and we couldn't hear the piano during session, with the parts of the songs where he was supposed to be comping and I had to go on stage and crawl under the piano to make sure that the microphones were working. So here I am crawling - they're performing, they're all in tuxedos performing at the Town Hall with this stellar band - and I'm crawling underneath the piano in the middle of a tune, just to make sure the microphones were working. It's pretty funny!

[Federica]: Speaking of big names, do you think that when audiobooks were being made popular, you said that they weren't even called audio books up to some point, the involvement of celebrity actually helped people get closer, get familiar, want to buy audiobooks. Whereas today, because it's more common, we actually look for titles which we may like, it's more about the books, we don't necessarily need a celebrity in the production to attract us to a product, it's more about the book.

[Richard]: Yes, in the early days that I was it, celebrity helped sell the book. Now people are more savvy, so they're more driven by who the author is, although a lot of people become devoted fans of specific readers and over the years there are now hundreds of professional audiobook readers, that essentially all they do is read audiobooks and they're really good at it. Whereas, when we did celebrity talent, more often than not we were selective about who we picked but not everybody was a spectacular reader, whereas now more often than not, we have really good readers. We do have occasional author reads, [there] aren't probably more than occasional [authour reads] and a lot of them don't realise how difficult, physically difficult it is to do the reading of an audiobook. Because it's a record that is preserved forever and it's different than say public speaking where even though a public speaker might be recorded for archival purposes, when they make mistakes or stumble or don't say something completely clearly, because their diction isn't terrific, it's alright. But when it's an audiobook and it's an audio only presentation, those things really make a difference, so if you have someone who can't crisply pronounce words and do it in a rhythm that is pleasing, because sometimes the quality of somebody's voice is just off-putting to the listener or their cadence, some people just don't have the music in them and a lot of times authors think that because they wrote it, they can best express it. But a lot of times that's not their talent and I often use the analogy of well you don't see screenwriters starring in their movies, they might be great screenwriters but that doesn't necessarily make them great actors and they might even know the difference between good acting and bad acting, but their talent is writing. Now, there are people who are multi-talented, that can work equally well in different disciplines, but really, more often than not, one person's main talent is where they focus.

[Federica]: When you're in the studio, especially for the long sessions, you have to pay attention to the clock that's ticking or the scratching and all these noises and make sure that the sound quality is always top. So do you have enough neurones available, I would say, to follow the story, so do you enjoy actually what's being read?

[Richard]: Yes, usually there's three people; there's the reader, there's the director and then there's the engineer. And as an engineer, you're listening more for the technical things, though you do pay attention to - if it's a fiction book where there's characters - you want to make sure that they're using the correct voice. So you listen for that sort of stuff, but you listen more for the technical stuff and a lot of times you don't, as an engineer, you don't hear a lot of the story because you're really listening more on the technical side and the director is really listening more for the performance side of things and continuity in terms of characters and that sort of thing and the engineer focuses on the the technical side, but you kind of mix both. And I've done situations where I've engineered and directed and it's difficult because both of them require different kinds of concentrations, so doing both simultaneously can be difficult for a lot of people, because of the economics of things, not so much because they prefer to do it. But this business is not a business where you make a lot of money as a director or, even necessarily as a talent. [The] pay scale has come down for professionals in the business considerably since I started, the people who do work a lot do well, but they work very hard for that money. Because as a reader, you don't just show up and start reading, some readers will read the book twice before they even show up at the studio so that they are totally prepared, and then they read it again for for the actual recording. And they actually practice it out loud, even reading it is not the same as saying it out loud and sometimes wrapping your mouth around words is more difficult than you would think and some books lift off the page easier than others, some don't make good audiobooks, sometimes you know there are books that we put out, but it doesn't translate well to audio. Certain things, where graphs are involved and that sort of thing, you can't make that happen in an audiobook. So a lot of times, that kind of information is lost, but fiction, that's really where the magic happens, sometimes you can just be totally spellbound by people's performances.

[Federica]: I think that your job as audio engineer for audiobooks is really important because, if you think about it, an audiobook takes many hours to be listened to and we often listen to audio books in our headphones and rarely there is music, so it's really just the voice in our ears, it's such an intimate thing - it's almost whispering in your ears - it's really intimate. So, I hope that your colleagues in the music field don't look down to this craft, because it's actually such a service you give to people that then have access to sometimes great works of literature, it's amazing.

[Richard]: And for over 30 years, I have been an advocate of the highest quality recording for spoken word and it's always been relegated to - when we were first putting out analog cassettes - we would use the lower quality tape and have the cassettes in high speed duplication process, which used to make me crazy because I would listen to the recording that I made, the master, and then I would listen to what we sell as a product, the cassette or even the LP and I was always amazed at how poorly it sounded in comparison. Now, when I recorded analog, recorded 15 IPS Dolby A and then when Dolby SR came out - we used Dolby SR are at Cadman and Harper Audio - I used to love the way it sounded, it just sounded so real and warm and then I would get the test pressing, or a test cassette and I would just be amazed at the test cassette, you would hear the image kind of waver from left to right because the the high-speed duplication and there would be so much tape hiss because they used garbage tape. I used to say the human voice is the sound that humans know better than anything else in the world, because you hear your mother's voice and even noises from outside your mother's body, when you're a foetus, and our ear and our hearing is tuned to where the human voice is basically centred, so why relegate something that we know what it sounds like better than anything else to the lowest quality reproduction that we can do. And that just drove me crazy and it still drives me crazy, we record 16-bit 4401 here and their whole thing, well it gets mashed down to MP3, and my feeling is well the better quality recording you have, the better it sounds when it's compressed down to an MP3. But they don't listen to me.

[Federica]: I hope they do now, I hope they listen to this podcast. Is an audio book ever read by more than one person?

[Richard]: Yes, we do a number of multicasts and there's all kinds of headaches involved in that because, even if you record them in the same studio, it's difficult, it's a lot of work for the editor to put these pieces together from different recording sessions and make it sound like one cohesive thing. We've also done plays where it's multicast but you're doing it all at the same time, in the same place and everybody's there. What we do in the multicast audiobooks is some people will be in California, some in New York, some in Florida, Montana, whatever, and we've done stuff, I think we recently did something that had 30 or 35 different voices on it and that's, it's actually, it's a nightmare. It's logistically getting everybody to be in the studio at the right time, in the right place and because of the turnaround time, we start recording something and it's released in some cases a couple of weeks after we finished recording and there's a lot of work involved in from the recording process, to the editing, to having it proofed and then fixing what was revealed in QC [quality control], as we call it, and getting the actors back to fix things doing what we call pickup sessions. So when you add multiple people to that, it becomes really difficult, so it's expensive and it's a lot of work getting everybody where they need to be, at the right time.

[Federica]: Do you ever add music or maybe sounds like traffic noise or someone slamming a door?

[Richard]: Yes, well, when I first started, every title we did at Cadman had original music composed for it.

[Federica]: Wow

[Richard]: And it was, some of it was, just unbelievable. I did an audiobook with Glenn Close back in 1986, called 'Sarah, Plain and Tall', and I can't remember the person who we hired to do the music, but he did such an incredible job, I know I have his business card at home somewhere. But so we underscored, he wrote a theme and then they would write other pieces of music that would reflect the theme, not unlike a movie where you have a recurring melody, but you use different instrumentation, or less, or more instrumentation, or it's at a brighter tempo or a slower tempo. But, it got to be too expensive to do that, so then, we started using music libraries and they worked pretty well, and there's a bunch of international music libraries for this sort of thing, they're used in commercials as well. And now, because production time is so short, most of them don't have music at all and it's a real shame because it really can be evocative, but once you start adding music and or sound effects, you've got to kind of be consistent throughout, you can't just put it at the beginning and maybe toward the middle and then the end. Once you kind of dip your toe into that pool, you've got to continue it, otherwise it becomes a distraction to the listener. I did work on a title, the the movie Home Alone 2, where we did an audiobook of the Home Alone 2- we had Tim Curry narrate it, and then we had someone write music specifically for it and we did sound effects and ambient background and we still at the time, we were still working in analog so we did it on an eight-track Tascam, half inch Tascam analog machine and I wish I had a workstation at that time, because it would have made it so much easier. Because we had to do so much sub-mixing, particularly on the sound effects, we had a sound effects library but not every sound effect was exactly what we were looking for, so what we had to do is take that sound effect and augment it, either sometimes layer a couple of different kinds of sounds on top of it or actually make sounds ourselves, we dropped toolboxes and stuff like that just to mimic the sound from the movie. And it was so much fun and I would love to do more of that sort of stuff, but it's just too time-consuming and expensive.

[Federica]: I noticed in the list of your nominations, that there is a Grammy Award for spoken word recordings for children, so are audio books targeted for children a big chunk of the market?

[Richard]: Yes, some companies have a whole different division, like our children's audiobooks are done by the children's book department, usually it's freelanced out, but we don't do much of the children's stuff, although there's a tremendous amount of children's audio published. I have worked on quite a bit of it, but for the most part it doesn't come through here, we have five Studios in New York and we have ten in Los Angeles and most of the stuff we do is all adult and the children's stuff is usually done out of house. But occasionally, I do a few of them and I have worked on, over the years, probably a hundred or so.

[Federica]: We have talked about audiobooks now for a while, but we've mentioned already that you're also a musician yourself, can you tell us a little bit more about you, not as audio engineer for audiobooks, but as musician?

[Richard]: Okay well first of all, I don't call myself a musician, I call myself 'a guitar owner'. I think I play better than some people who were millionaires, who call themselves musicians, but I don't consider myself a musician. Music has always been a passion of mine my father was a singer in big bands in the 1940s

[Federica]: What was his name?

[Richard]: Rocco V. Romaniello, he sang with Carmen Lombardo's Orchestra. Carmen Lombardo is Guy Lombardo's brother, but my father's mother who was from Italy was afraid that my father would turn into a heroin addict or something, because that's what happened in the 1940s, there was a lot of drug use back then, believe it or not, so he never pursued it farther than that. So by the time I came along, he was out of the the music business, but he actually was quite a singer and had about a three and a quarter octave range, for a male that's pretty outstanding. And he sang in Italian, how much better can it get, I actually have two 78s that he recorded at NOLA studios, in New York in 1945, where he does a medley of about 13 tunes with just him and a piano player and of course the records are in absolutely terrible condition, but even then you could hear that he could sing, I mean he really could sing.

[Federica]: Was he singing around the house?

[Richard]: Yes, but my father died 49 years ago last week, so I was 14 when my father died and he had been sick from the time I was about seven, he had a heart attack at 44 years old, it was a rather devastating heart attack, as a matter of fact back then you couldn't visit your parents in the hospital if you were under a certain age, and he was in the hospital for a number of weeks and I almost didn't recognise him when he came home. So yes he did, he sang a little bit around the house but, unfortunately, he was very frustrated because he didn't pursue it, because he was good. He was 51 years old when he died, so...

[Federica]: I'm sorry to hear that, I guess that he gave you his passion for music though, that's where it comes from

[Richard]: Oh yes, I didn't start singing and playing till I was about 15 but I always sang to myself, I didn't start singing and playing in any kind of earnestness until I was about 15. So again, a late start. But early in my engineering career, I got to work with Malcolm Addie, who I mentioned much earlier in the recording, who was the chief engineer at Abbey Road from 1958 to 1968 and with him I've done about a hundred and fifty live recordings and we just did a recording in mid June, just before I met you, probably his last jazz recording. We recorded with a Brazilian jazz band up in Tarrytown, New York and he's gonna be 85 this Saturday, I'm going to his 85th birthday party and I think he's pretty much gonna hang up his recording shoes. But I met up with him in 1983 and have been his assistant since then, so whenever he goes out to do a location recording, if I'm available, I'm his assistant. And that's where I got to work with so many of these great jazz musicians, was on his recordings, I was the assistant on many of them, but I'm not a fanatic for jazz, I had never experienced real live jazz until I worked with Malcolm and I was just amazed that you could get 20 people together and they could look at this piece of paper with all these black dots on it and all come together and count it off and make music. The first album I worked on with Malcolm was at the studio that I was working at in Rutherford and we recorded a 20-piece band for two days and mixed onto the third day and we had an album, it was the Jimmy McGriff Orchestra and the album is called Sky Walk and it was on Fantasy Records. And we did two punch in's, that's it, we fixed two eighth note sections that were maybe half a measure long, that's it, everything else was recorded live, everybody in the same room, at the same time. We had Kenny Washington on drums, Jimmy McGriff on B3 and he played bass pedals on B3, so there was no bass player, Jimmy Ponder on guitar, Kenny Werner on piano and the horn section was - I forget exactly who was in the horn section - but it was a real classic big band horn section, it was five saxes, four trombones and four trumpets and we had everybody in the room, at the same time, two days recording and day three mixing and pencils down, we're done. When I got out of audio school, I thought I was going to make a record much like the way they were doing them in the late 70s and early 80s, where they do their rhythm section separate, do all the overdubs and sweetening and all this other stuff over the course of weeks and maybe even months and do 70 billion different mixes of one tune and I thought that's the way I would want to work. And after about two hours of that kind of work, I thought this is not for me, I'm more of what I call a documenter, than a fabricator.

[Federica]: Can you elaborate a little bit on these two concepts, what's the difference between a documenter and a fabricator?

[Richard]: First, documenting is more...I prefer live performance recording and there's a lot of things that go wrong in those kinds of situations. But they're much, I find them to be more magical, the imperfections are inconsequential compared to the magic that happens in a performance. Because as a performer my own self, when the audience is giving you positive feedback, it changes the way you play and when your bandmates or the people you're performing with are also doing that, there's a magic. Now, it's not that it can't happen in the studio, it happens lots of times, but when you listen to the great jazz recordings of the 50s, Miles Davis and the Ellington and the Basie stuff. All that stuff was done live and that was the magic of it, they had full orchestras in the studio and they cut live and a lot of the times there was a not an editable format, you couldn't edit a 78, it wasn't until tape came along that you could actually edit, say the first half of the tune from take one and to take three versions. So I think of myself as more of a photographer, where I'm taking a picture of something, I try not to put my thumbprint on it, I just want to capture what's happening.

[Federica]: I think the perspective of the documentary shows a great love for the acoustic event, for the live music that's happening

[Richard]: Well, I feel like I'm a witness, as opposed to somebody who's making something, I'm just putting my audio cameras in place and letting them do the work. A lot of engineers, particularly in the rock-and-roll business think it's all about them. And the truth is, all the engineering finesse in the world is almost, as far as I'm concerned, is meaningless if you have to auto-tune somebody's voice or instrument. That stuff just makes me crazy, everything is re-configured to be on the beat and right on where it's locked in on a grid on your Pro Tools. To me, that's just not music, you're saying like electronic stuff, I mean music is supposed to breathe it slows down and it speeds up, yeah it's supposed to be at a specific tempo, but it's got to breathe and if it doesn't it's not gonna be, I find it not to be as moving. And maybe that's just my bias, but music doesn't have to be performed by precision greatness. I appreciate precision greatness, the Al Di Miola's and the John Mclaughlin's and that sort of stuff that can play a million notes. But it still comes down to saying something musically and just today I was listening to one of my favourite Blues guys, Albert King, and the guy played very few notes in comparison but, man he made them say something, I don't get that from a lot of contemporary stuff, I get it, it's a business but to me I don't listen to a lot of that, I don't listen to any of it to be honest with you, I listen to what I like.

[Federica]: Speaking of what you like, there is something you said when I was in New York and we spent that couple of hours chatting when you were showing me around your studios, something that really stayed with me, most people say I like music, but you said I like noise.

[Richard]: I do, one of my favourite sounds and it's a terrible sound when you think about it, is a needle being pulled across a record, it's just, I don't know what it is about it, but the sound just does something, it can evoke so many different things. My first tape recorder I got I was 10 years old and GI Joe dolls had just come out the year before and it was the first time boys had dolls. And I got this $10 tape recorder that had three inch reels and a crystal microphone and it was an ACME brand tape recorder and I did background tapes for my GI Joes. So I would put the the microphone on my picnic table in my back yard and tapped with my fingers on the wood for machine-gun fire and pretended to be bombs going off and that sort of thing. And that was my first introduction to audio.

[Federica]: Creating your own soundtrack.

[Richard]: In 1965, little did I realise that 16 years later I would become a recording engineer. And actually that's a pretty amazing story as well, if I may, when I met my wife in 1980 and in 1981 we happened to be somewhere and ran across someone that she knew and that person worked for the county government and he was involved in a program called CETA, which is the Compulsory Education and Training Act and which was a program that Jimmy Carter introduced when he was President. And because of that program, I went to their Learning Center, I forget exactly what they called it, but where I was evaluated over a six-week period with about 15 other people. And what they would do is, they would see where your strengths and weaknesses are and they would help you find a career, like electrical wiring, or I made a toolbox out of sheet metal, there are a number of different workstations where they tried to see what your aptitude was. And at the time I was 26, so I had been a manual labourer for the last eight years and was going nowhere fast and they said, well you scored high enough on these aptitude tests that we will give you enough funding for a year's worth of trade school in any discipline that you would like, so long as it's an accredited school. And a friend of mine had gone to the Institute of Audio Research and he recommended it and I went there and I liked it, and I always wanted to get into audio, but I didn't know how to and that was my introduction to audio and so the government paid for my tuition, they paid for my books, and my calculator, and my lab fees and they paid me a dollar fifty an hour for classroom time and ten dollars a week for car fare or subway fare. And as a result of that, I went from September 1981, graduated in September 1982 and since then, I have been making a living as an audio engineer and had I not had the luck of running into this person and him hooking me up with CETA, like I said I'd be making cardboard boxes somewhere or it'd be a landscaper or something - not there's anything wrong with landscaping and making cardboard boxes - but I actually find audio far more interesting.

[Federica]: This doesn't sound just like a nice training program, it's a program that can turn lives around.

[Richard]: It did.

[Federica]: Of great social utility, I'm sure that if it still existed it would be repealed by this administration.

[Richard]: Well, Reagan repealed it, which is exactly what happened, Reagan repealed it, I got in just under the wire and it opened up a world to me that I would have never, ever seen and it's a result of the CETA program that myself, and probably thousands of other people, the saying you can give a man a fish or you can teach him to fish, well I got taught how to fish and thankfully I've been able to do that and I hope to do it for another 10, 12 years before I have to retire.

[Federica]: I wish you can do that and I also wish that you keep playing music and being a musician. I anticipated a small surprise before, the surprise is that we would like to close this episode of Technoculture with a song that you wrote, is that correct?

[Richard]: That is correct, it's called "Helps not to know me well."

[Federica]: There's a story behind that title.

[Richard]: There certainly is, many years ago, I think it was still in the 90s I was working with an actress named Katherine Walker and at the time she was married to James Taylor. And she was telling me and my partner, Rick Harris, about this new album that was coming out, it was a live album and in between the songs they left in some of the banter between James and the audience and in the middle of one of these bantering sessions, somebody screams out from the audience, "James, I love you", and he says "It helps us not to know each other well." And I said to Rick, I said, that's a song and about 15 years later I wrote a tune called "It helps not to know me well" and then to make things even more crazy when I was at the conference in Culpeper, with you, we were lining up to have our picture taken in the lobby which is being posted, I believe, in Mix Magazine and Profound News and some other magazines.

[Federica]: And rightly so, it was a memorable conference.

[Richard]: Oh, it was tremendous, best AES event I've ever attended, but as we're lining up for the picture, George Massenburg sidles up next to me and and my nametag happened to be turned around so you couldn't see my name and he says to me, "Hi Ritchie, how are you doing?" I said, George "I can't believe you remember my name", he said "Well you know you have a presence on the Internet". And I said, "Really, well it helps not to know me well" and he looks at me, he says "That's from my record!" And he either produced, engineered, mixed the James Taylor live album that I was talking about with Kathryn Walker, but that was 25 years ago. And the fact that George Massenburg remembered me after talking to me one time, maybe eight years ago, I was just dumbfounded, I didn't know what to say, George Massenburg, just one of the greatest all-time recording guys ever. And I was just over the moon that he even remembered me, but that recording, that chance recording that happened in the 90s and then gets kind of echoed back in 2018, it's pretty amazing.

[Federica]: So tell me about the recording, this is recorded by you and your band, correct?

[Richard]: It's a live recording of my band, the Original Famous Ray's and we're a New York-based band and for New York people, in New York City there are about a hundred and fifty different Ray's Pizzas that all purport to be the original famous Ray's Pizzeria and our hope is that one of them will sue us for using their name and then we will actually become famous. We were leaving rehearsal one night and we didn't have a name for the band and I was in a band previously and we never had a name and it just kind of disintegrated, and I was certain that it was because we didn't have a name and an identity, so we were leaving rehearsal one night and in about a two-block span we passed two Ray's Pizzas and I said oh we'll call ourselves the Famous Ray's and found out there was another band called the Famous Ray's, and I said well we'll do one better, we'll be the Original Famous Ray's, so this recording is the Original Famous Ray's performing at well-known music venue here in New York City called The Bitter End, and it was from December 30th 2017.

[Federica]: Thank you very much Richard, let's listen to the song.

Thank you for listening to Technoculture! Check out more episodes at technoculture-podcast.com or visit our Facebook page at technoculturepodcast, and our Twitter account, hashtag technoculturepodcast.

Page created: January 2019

Updated: July 2020

Last update: July 2020