Redefining death: The neurosciences understanding of human consciousness

with Steven LaureysDownload this episode in mp3 (34.70 MB).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

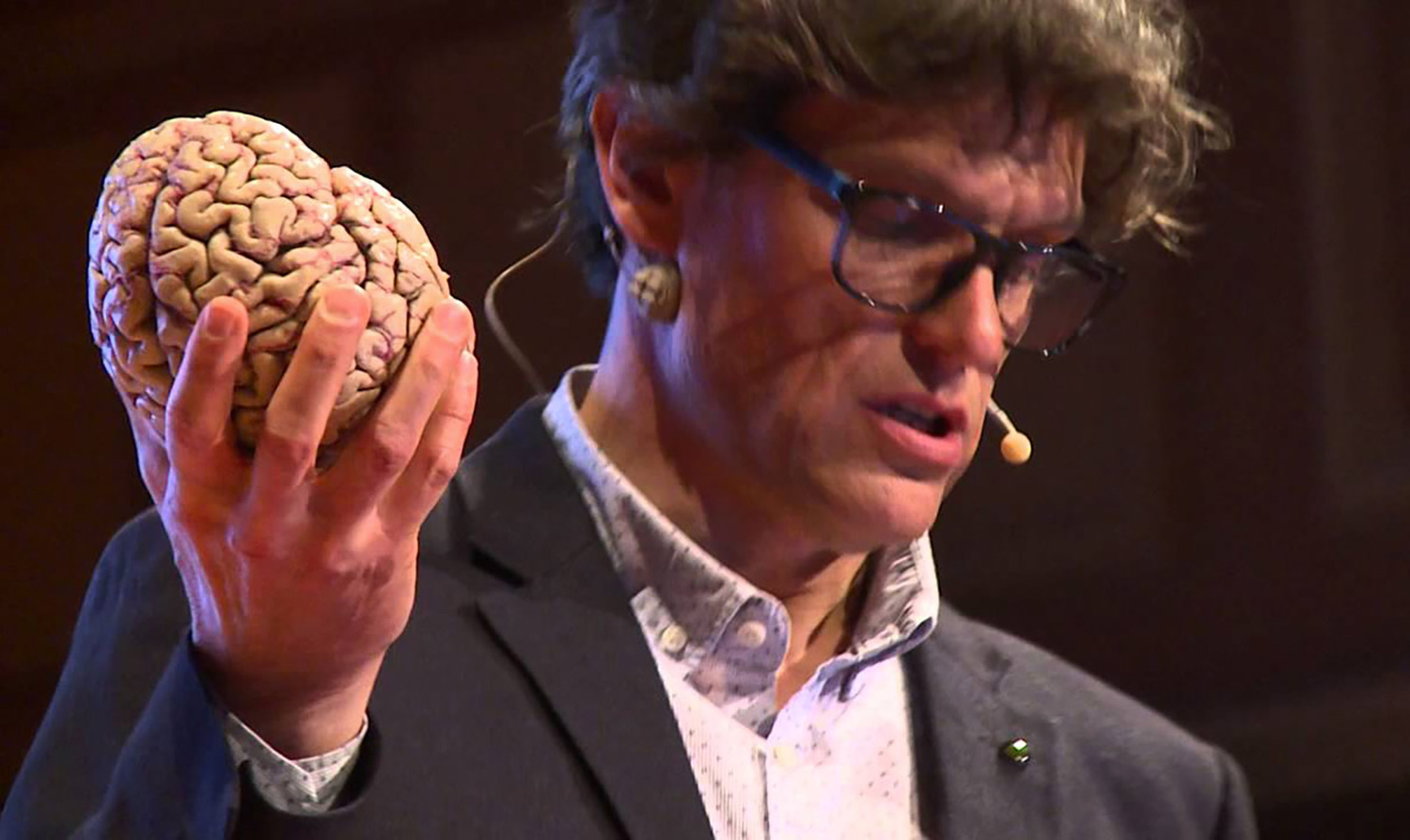

Steven Laureys is a neuroscientist who studies the states of consciousness in patients in a coma. His work is much more diverse and complex than this, but in a nutshell this short summary should already raise your interest. Who isn't fascinated by the mysterious feeling of "being there", what makes us conscious? Steven Laureays leads the Coma Science Group at the GIGA Consciouness Centre of the University of Liège in Belgium. He is the author of several publications on consciousness, awareness, coma and the recovery of neurological disability, and the recipient of honours and award for his scientific and communication activities.

I was attracted to Steven Laureys' work because it's the quintessence of state-of-the-art technology applied to the investigation of an elusive yet universal phenomenon like consciousness, something that is not unique to human beings but that defines us in a particular definition of consciousness. Because animals are aware of the environment too, they are responsive and they feel emotions in their own way, but we are the only "animal" who interrogates itself about the "being there" and who developed the technology to do so in a scientific way.

I approached Steven Laureys as a neophyte in the neurosciences, asking questions that probably everyone would like to ask if given the chance, including "what is consciousness"? Now this is a philosophical question in a way, but science is narrowing the area of the "unknowable" and it is interesting to hear what definition of consciousness neuroscientists have. It was an incredible hour I spent talking with Steven Laureys in his office in Liège, and, for the record, the first interview I recorded in chronological order for this podcast. I was indeed very nervous! Still, it was hard to bring the conversation to a close: there are so many interesting topics to discuss, such as the fundamental concept of "redefining death", in terms of brain activity and not of heart beat. We take so much of today's medicine for granted, but some of it is very recent! The possibility to apply "therapeutic obstinacy", with all its ethical implications, is only allowed by the ever more sophisticated ways to keep someone alive, in a vegetative state. At the same time, being able to detect pain in patients that can't express pain vocally or elseway, allows us to take better care of them.

This seems to me one of the most fascinating fields of research: science can now measure and reformulate problems that historically have only been prerogative of religion or philosphy. Near death experiences, for example: are they a scientific problem, or simply fantastic stories reported by people with a vivid imagination? What I loved about Steven Laureys' approach is that he combines an impeccable scientific method with an open mind attitude, avoiding dogmatism - which is precisely how science should advance, "being critical about your own criticism". Critics say that altered states of mind cannot be studied: Steven Laureys suggests that we do, "trying to confront what you think you understand with what you think you measure."

If you've had a near death experience, or know someone who has, please get in touch with Steven Laureys' research team at: coma@uliege.be.

I have learnt a great deal from Steven Laureys, and one of my favourite quotes from this interview is: "The Dalai Lama is a good scientist"! Yes, Steven Laureys has met the Dalai Lama as well as other Buddhist monks, and has involved them in his experiments on consciousness and the effects of meditation on the mind. I hope this podcast episode will have positive effects on your mind!

GIGA Consciousness Centre: https://www.giga.uliege.be/cms/c_4113263/nl/portail-giga

Steven Laureys' profile at the Coma Science Group: http://www.coma.ulg.ac.be/home/steven.html

EuroScientist

This episode was re-published on EuroScientist in April 2020 (see episode on EuroScientist). On that occasion, I met Steven again in his office in Liège and he showed me some brain-computer interfaces including one that he wore running the New York marathon in 2019.Selection of contents

00:34 Where does the state-of-the-art technology that neuroscientists use today come from? Who designs it, who produces it?

00:43 What made Galileo such a good scientist is that he had good telescopes.

1:49 Steven mentions the European project LUMINOUS (2016-2019): Studying, Measuring and Altering Consciousness through information theory in the electrical brain: http://www.luminous-project.eu

3:05 What is the main difference between a fully functioning brain and a damaged brain? What stands out in the observation of these brains?

4:42 Why are small wearable devices relevant to Steven Laurey's work, as opposed to large and expensive equipment found at the university hospital where he and his team work?

6:31 Steven talks about wearable devices for self-monitoring purposes, and gives some examples.

6:50 Steven ran the New York marathon in 2019, wearing a device that monitored his brain activity throuout the performance.

8:33 The ability to stimulate the brain and influence its activity may open up new application scenarios besides rehabilitation, including leisure, enhanced creativity, super-consciousness, etc. I ask Steven what he thinks about it.

9:35 Following up on the previous point, about applications that are not medical rehabilitation, Steven acknowledges that brain-computer interface technology can be used for less than good purposes, but he also says that this is the case for all of science - for example, radioactivity.

10:05 Steven talks about the importance of submitting scientific work to ethical boards, but also of the importance of "courage and creativity" in bringing care to suffering patients.

14:03 How is Europe doing in comparison with the rest of the world in terms of ethics regulations and the relative administrative burden on the research?

15:50 "I would like to see more science in the media" says Steven Laureys.

16:28 The balance we need to strike between doing difficult research and protecting the citizens is an open discussion that we need to keep having: technology advances and allows us to do new things, and as a consequence policy regulations must follow.

Companies and startups mentioned in the interview

1:20 g.tec medical engineering GmbH, in Austria: https://www.gtec.at

1:52 Neurosteer, in Israel: https://neurosteer.com

2:35 Starlab, in Spain: https://www.starlab.es

Go to interactive wordcloud (you can choose the number of words and see how many times they occur).

Episode transcript

Download full transcript in PDF (121.87 kB).

Host: Federica Bressan [Federica]

Guest: Steven Laureys [Steven]

[Federica]: Welcome to a new episode of Technoculture. I'm your host, Federica Bressan, and today my guest is Steven Laureys, a world-class leader in the field of neurology of consciousness. He's the leader of the Coma Science Group at the GIGA Consciousness Centre at Liège University in Belgium. Welcome, Steven.

[Steven]: Hello.

[Federica]: Thank you for being on Technoculture. I would like to start by asking you to define for us the word 'consciousness'. 'Consciousness', as well as 'brain', are important keywords in your work, but it's also words that we use in our everyday language, and they evoke different images, so this makes them also very fascinating, but in your work as a scientist, 'consciousness' must have a very clear definition, and it must have attributes attached to it that are measurable, I would imagine. So can you tell us how you define consciousness in your work?

[Steven]: Well, there, we already hit the first problem, because we do not have a definition of consciousness where everyone agrees upon. If you would ask a philosopher, he would have her or his definition might be a quite long one different from the informatician talking about artificial intelligence or the person doing animal research, the anesthesiologist, neurologist, medical doctor. So I think it just illustrates our ignorance. Consciousness is tremendously important, and that is, of course, well illustrated when you have a damaged brain and you lose consciousness. Then it really becomes clear how central it is. And yet it has for a very long time not been a serious centre of study. It was kind of tabooed, and that, I think, is a pity. So I think we should have more scientists interested in this big mystery that human consciousness is. So currently, our definition for a medical doctor (which is what I am) is just operational, and we will reduce what we call 'consciousness' into two dimensions. That's wakefulness (and that we will score at the bedside by looking at eye opening; it's very basic), and then we will talk about awareness of the environment and look whether patients answer to simple commands, but there's many other dimensions. One I think is very important regards internal awareness or maybe self-awareness, this little voice talking to yourself right now permitting your brain to have this very rich mental imagery, and so, well, very briefly, what our lab has shown is that it can be useful to split it down because also in your brain, you got different networks that seem to be critical for the emergence of these very complex functions.

[Federica]: You talk about being awake. You can also tell if an animal is awake or not, and we're thinking of being awake as being conscious, so having consciousness. Can you draw a line, explain a little bit the difference between an animal's being awake or a human being being awake? Do animals have consciousness?

[Steven]: I think a historical mistake was to consider consciousness as all or nothing, black or white, and that is very probably false. You can be more or less awake more or less aware of your surroundings, of yourself, and of course, in my field of expertise here with the team over the past, well, nearly 25 years, we've been showing that in patients with very severe brain damage, despite the fact that from the outside, we think they're unconscious or comatose, sometimes there's more going on into their brain, in their mind, and that, of course, is terribly important. But it's historically been similar for newborns. Also here, we can't ask them the question, they can't talk, and for a long time actually, when I was at medical school, we still considered that newborns couldn't feel pain, and now of course we know better and also act upon that knowledge and give them painkillers, which was not the case. The same for the very old, the so-called end-stage demented, sometimes referred to also as being vegetative, and studies show that they do have emotions and also pain perception that you refer to, and that also has consequences. And, of course, there is this, for me, historical error where man has always considered him as the centre of the universe, and that has been difficult to accept and also a kind of, well, one could speak about the fight between religion, philosophy, and science we are not the centre of the universe and that took a lot of time. Big scientists (Copernicus, Galileo, some even gave their life like Bruno), still Darwin is not accepted by all religions, and it's difficult for us to accept that, and definitely the science of consciousness is a difficult one. And of course, from a biological point of view, it's just not possible to defend this view, quite arrogant view, that we would be the only animals with consciousness, a spirit, a soul, and... Well, I think, for me, this is probably a big revolution in bioethics, and again, there are consequences. I do think it's clear that animals are sentient beings with emotions, including pain.

[Federica]: Is it possible that when we say 'awareness', we in fact mean self-awareness, and this is why we get it wrong? Self-awareness is probably just sort of a subset on the higher end of the spectrum of all the possible levels of consciousness.

[Steven]: Absolutely, and there again, it depends how you will define self-consciousness. So definitely animals also make the difference between their own body and the external environment, and that is needed for survival, but then to have a symbolic representation about you as a being within your society, of course, has different levels of complexity, and this is... It's not just a linear thing that we see emerge throughout the animal kingdom, but again, I think throughout history, we've been looking very hard to find what is uniquely human. Is it language? Well, it depends how you define it. Is it the fact that we can make tools? Well, obviously not. Tests have been developed, like recognizing your own face in the mirror, and now there's a couple of animals that pass that test, but even those who don't pass the test, well, can we really claim that they're just only a bunch of reflexes of instincts and without any capacity for reflection, for social intelligence? And so every time I'm asked this question and I look into a specific question, I see that my colleagues who are experts in these fields of animal consciousness, well, have made wonderful discoveries. And we used to say, 'Well, he has the memory of a goldfish,' but actually fish are quite intelligent beings and with a very rich social life and interactions. We just only recently start to look at it seriously, I think.

[Federica]: At the beginning of some of the talks you have on YouTube, for example because you're also very active as a public speaker in science popularization you say that in the past, any reflection around consciousness, the 'study' (quote-unquote) of consciousness was prerogative of philosophy and religion, and only today with today's technology we can actually collect objective data about this elusive phenomenon and try to study it and say something about it. This is very close to the core interest of Technoculture because it's not just about how technology impacts our experience as humans, our everyday lives, but also how it changes the way we do research, the way we acquire new knowledge. So was the type of research you do possible, say, 50 years ago, or it was not possible at all? Of course, some research fields were changed by the new technologies, whatever they are, every other technological generation, but some research fields were actually made possible. You're collecting data that you couldn't collect before. It's not just automatized, or you can have big data whereas before it was a manual process. So what technology and how has technology changed this field, and, if I may, also, what do you see in the future?

[Steven]: Personally, I think that technology is tremendously important and it actually defines maybe the frontiers of knowledge. Galileo would not have been able to test his theories without a good telescope. Now, our telescopes are machines that can zoom in into the working brain, and that has helped us tremendously. It was very difficult. We had, of course, historically and this is maybe very special about the study of consciousness that it's a first-person personal experience, so there is a lot of of course, historically, philosophers have been thinking about this problem, asking the same questions as we do today. Religious scholars, the Buddhist tradition, these are really athletes of the mind. For centuries, for millennia, they have been observing what was happening in their own mind, sharing it with others, and that is powerful, but I think it also is confronted with a limit, and I'm very happy that we have machines and we can now confront both areas of expertise. The science of the mind and that is me and you, each of these little selves having experiences and trying to share them, but with the third-person method as a scientist, I'm making so-called objective measurements using these machines, using this technology, that, I think, is terribly important and it has helped us tremendously, but we shouldn't be too arrogant. Nobody understands how something material, the brain, we think is important, creates or somehow gives us this feeling we call self, we call consciousness. So let's not be arrogant. This is a big, big mystery. Some even say it's impossible. I think that is, well, dogmatic, and I wouldn't a priori...

[Federica]: Sounds like the ultimate mystery. Right?

[Steven]: Maybe. Maybe, just like the origin of matter, of the universe, but again, every time historically we said, 'This is impossible,' somehow we could make progress. So to me, it's about finding this right balance between not being too arrogant as a scientist (and there's very little we understand about consciousness, and our ignorance is huge, and what we measure with the machines is indirect, is imprecise and we should be very critical about that but it's also helpful), and at least we should keep trying. I would like a machine that permits me to measure in real time at the millisecond precision what's happening in these thousands of billions of brain connections we call synapses, and I don't have that machine. I have MRI, functional MRI, and I have high-density electroencephalography. I have here at the Centre in Liège all the tools that we can buy that exist, and yet I feel frustrated because it's indirect, and then I need to zoom in, basically put an electrode into the brain, and I can make tremendously high temporal resolution recordings, but it's just of a very, very tiny part of the brain. So to get the full picture, I think we will need some more technological breakthroughs.

[Federica]: How does matter produce subjective experience? That's a hell of a question. The body does not produce consciousness as it produces urine, for example. So indeed, when you want to look at consciousness, you have to look at it indirectly. Now, what do you look at, exactly? I read here that your research group has access to state-of-the-art multi-model imaging. What does that do? What kind of data you can extract from there?

[Steven]: So, well, as a neurologist, of course, we look at the brain, and we see the damaged brain. In our case, it's people who are survivors of a very important traumatic brain injury or who had brain bleeding or cardiac arrest and were resuscitated, but there's very important damage to the brain that we can see, and then compare that to, well, how are they: Are they conscious or not, all the degrees in between. And trying to identify what we call the neural correlate of consciousness, and we could, through these different machines, identify two awareness networks. So we think that there's critical networks. It's not just a small region. It's widespread probably for each hemisphere. You have these networks for internal and external awareness, and that we do by all possible means. With MRI, we can make pictures of the brain, high-resolution pictures of the gray matter, those billions of brain cells. We can also, with another type of MRI acquisition, look at the white matter, these brain bridges, the connections, and that is very useful. And in traumatic brain injury, often these connections will be damaged. It's what we call diffuse axonal injury, and that can make you unconscious. We will also look at, of course, brain function. With functional MRI, we see changes in perfusion of different brain areas while the brain is resting and while we stimulate the brain. We'll measure the electrical activity using EEG. We will inject radioactive sugar because the brain use a lot of energy, and that, again, gives us images. We will perturb the functioning of the brain with TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and see how that influences while we measure the electrical activity. So we will approach a problem from all possible angles. They all have their strengths, but also weaknesses, and then put that together and try to say something, of course, that's useful for the patient, because we have patients coming from all over Europe for one week and we try to reduce the uncertainty. Is this person conscious or not, and if so, to what degree? Will she or he recover? What can we do to stimulate the so-called brain plasticity? But of course, while doing that, it helps us scientifically. What is consciousness? And we also look at the anesthetized brain, the brain on drugs, the sleeping dreaming brain, the brain in hypnosis, in meditation, the brain of astronauts and how it adapts to zero gravity. So all these angles help us to understand this huge mystery, human consciousness. Technology, to me, is critical. So half of the team (we're about 40 people) are engineers, informaticians, physicists, and they work together with the clinicians seeing the patients and translating that knowledge to, well, real clinical decisions, sometimes about life or death.

[Federica]: From a technological point of view, is this a fast-evolving field?

[Steven]: Well, it's impossible for me to predict what we will use in years to come, and nobody predicted that one day we would be using a magnet to see inside your body, to see inside your functioning brain. I do hope that we will have better technologies, because the ones we currently have, they give us beautiful images, and I use them every day, but I think we should also be very critical about them. They don't show us thoughts. They don't show us consciousness, perception, emotion. So, well, it's wonderful to have them, we're improving them, but I do think that we will need a complete paradigm shift, something that gives us a much more detailed image measure of this terribly complex organ that the brain is and that is permanently changing where, of course, we've been talking about this material object that the brain is, but maybe we shouldn't also take that as a dogma. Maybe the laws of physics and biology currently do not permit us to make this giant leap forward in understanding what consciousness is. We work together with an American scientist called Giulio Tononi. He developed a theory that says that for a system including a computer, by the way to be conscious, the information needs to be integrated, and when we can define what is information, what is integration, can we put maths behind that, can we test it in human beings. This is what we did, so we developed a test and we tried to put a number on consciousness. This is very provocative, very, well, simplistic, but it turns out to work. When you sleep, this number is below 33%. When you're awake, when you're dreaming, it will be higher. And so also in anesthesia, we tried many, many drugs here in Liège, the number is below, and so now we use this test trying to falsify this theory but also then make it useful clinically in patients with brain damage, but there is still a lot to be done, and we're very far, I think, from truly understand this big, big mystery that human consciousness is.

[Federica]: If it's hard to predict the future, let's look back for a moment. You've been in this field for at least two decades, and you're a leading player in this field, so can you tell us how was research in this field 20 years ago, or more precisely, what is the one piece of information that we have today and that we didn't have 20 years ago, like a major advancement that has happened that you witnessed?

[Steven]: Maybe to me the most important is that it's no longer taboo. Well, still I think there's work to be done. Many of my colleagues consider it like soft science, like not really serious, and I think that we really should put more effort. It's such a big problem. It has such huge clinical, ethical, societal consequences that we cannot just auto-censor this as we have done for a long time, which was the case when I started in the '90s. Now, every day, there's new papers being published. Probably, there's many... Well, there's too much papers. Right? This is also a problem in science that, you know, there's many, many journals that we don't need, many, many papers that we don't need, but at least there's a lot of activity. So the knowledge is increasing. To me, it's interesting that we can now test this hypothesis that we have these two consciousness networks. External awareness probably depends on this frontoparietal network with the thalamus (this is a part deep inside the brain, this telomere cortical loop, so it's interactions within these networks and this deep center that probably are critical and that needs to be better characterized), and then there's internal awareness, which is another network deep inside in the brain, and how they permanently interact with the memory systems, the wakefulness, arousal systems, emotion. So this is what we're currently looking at, and I think every week there is fascinating new knowledge, and that is very good, but still, I think that we are maybe at the stage of quantum physics before Max Planck.

[Federica]: Something that really fascinated me when I was preparing for this interview is to find out that your work has quite a number of consequences that might not seem obvious in the beginning, ethical and clinical consequences. For example, unconscious people who cannot express themselves and say, 'I feel pain,' well, by monitoring their brain, you can actually detect evidence of pain being there, so you see that they feel the pain even if they cannot say it, and you can treat these people accordingly, so give them some solace. And that sounds to me like a very good thing. Another example, I understand that there are two machines in the world that can detect pre-birth brain activity, that is, brain activity in fetuses, and by the way, it was already found out that there is some brain activity going on, so probably there is some learning or memory function going on, and this may have very important ethical consequences or at least inform the debate. But there is a quite more general issue that I realized when I was learning about these things and that it's probably very banal, but I'm still going to ask you, and that is, did coma exist in the ancient world, or is something that is only possible with modern medical technology? So coma is not really a medical condition. Coma is not a disease. It's a state, and it's a state where you need machines to support your life functions, and come to think of it, coma is never mentioned in classic literature. And I took it so much for granted, but then I was in doubt and said, 'Really? It should be like a big thing that everybody knows,' or I was the only one not to know, I don't know, but it didn't seem obvious to me. Is coma just something that we can have in the modern times? So once upon a time you would just die; is that what used to happen?

[Steven]: So, of course, the art of medicine over the past millennia went through a lot of changes, revolutions. I think we don't appreciate that enough. When we're sick, we go to the hospital whether it's Sunday, in the middle of the night, Christmas and we expect a team to be there to use these technologies (my case, brain scans) when there's a bleeding or a meningitis, giving you antibiotics, taking care of you, saving your life, increasing your quality of life. And that's tremendously important, and I don't think we appreciate it enough. So clearly, this knowledge impacts each and every one of us because we're all patients. And of course, when we talk about the brain, brain diseases, both in the field of neurology and psychiatry, (and psychiatry, for me, is neurology we don't really understand), but it's important to each and every one. In Europe, one out of three will at one point be confronted with some brain disease, so it really is important that we increase our efforts, and we do need technology, and well, a lot can be improved and has consequences, as you said. Already, the definition of life or death, that was quite straightforward for millennia. When are you dead? Well, when your heart stops beating, you're lost breath, your brain stops, and these three critical functions the heart, the lungs, and the brain they were related one to another. And then in the '50s, suddenly there was a new technology, the artificial respirator. It was a revolution. It was the start of what we now call intensive care. It was the first time we were thinking about therapeutic obstinacy. When should we also have the courage to stop this machine? It was also the reason why society, medicine, had to redefine death. Now, there's basically two ways of dying. The new way which is in intensive care can be that your brain is dead, the so-called brain death criteria. Terribly important. It was directly the consequences of technology, and again, how that will be in ten years, in a hundred years, we don't know, but probably it's going to be different.

[Federica]: Is it true that if brain death is correctly diagnosed, then you never come back, so to speak like goodbye, you're gone whereas if your heart stops, chances are that you can be resuscitated? So this is where you can really draw the line, to say when you're dead or not.

[Steven]: Yes, this is very important. We also study at our university in Liège so-called near-death experiences. This is fascinating. Again, it's an area where there's a lot of taboo, it's not easy. A lot of movies, best-selling books, very, very little science, so we want to change that. By the way, if anyone listening to this had such an experience, please share it with the lab. Our lab is coma@uliege.be.

[Federica]: We will provide this reference in the description...

[Steven]: Wonderful.

[Federica]: ... of the podcast.

[Steven]: And there's different scientists here listening to these stories. We now have more than 1,300, but as you rightfully say, these people were not dead. They were not braindead. They had sometimes a cardiac arrest, a severe coma, but they survived it, and afterwards, they had these very rich and intense memories. And I think we can learn from them also in terms of understanding consciousness, and it's a pity, again, that there's so little science, and, well, maybe this program will help us a little bit in the right direction.

[Federica]: I really hope so, and I think that by now everybody is like all ears and listening because who doesn't want to know these things? I find it quite amazing that now science is looking into this. So I would like to ask you one more question about this. I heard you say in one of your talks that you can elicit a type of experience that is then reported by the subjects as a near-death experience. The report is also quite consistent across subjects. That, for some reason, triggered this thought in my mind that if you can elicit something artificially, it could even be like the feeling of being in love, whatever feeling that you can just elicit artificially, deliberately, from outside by touching something, by doing something, that that would make the experience less real. Do you think that this makes any sense, or what is the relation also between the same type of experience as it is reported when it is elicited and when it occurs spontaneously? Can you talk about this a little bit, please?

[Steven]: It's a very good question. So what is real? What's happening right now in your mind, isn't that real? To me, it's real, and so as a medical doctor, of course, I listen to people. They tell me, 'I have a headache. I got pain here or there,' so I just need to trust them. Right? It's their reality. As a scientist, of course, I want to measure things and I want to explain things, but we shouldn't make the error, I think, again to see this as black or white, believers, non-believers. Some of my colleagues say, 'Well, why are you studying near-death experiences? This is just, you know, crazy people, crazy stories. We understand it's just an hallucination, chemical thing in the brain or lack of oxygen whatsoever.' I would disagree. We don't know the phenomenon. Others would say, 'Well, you can't study this. This is, you know, just proof of the soul leaving the body or the spirit or some cosmic consciousness.'

[Federica]: 21 Grams.

[Steven]: 21 Grams. Well, 21 Grams actually, historically, was a medical doctor a hundred years ago, more, who tested his hypothesis. He said, 'If there is something like the soul, and when you die, it leaves your body, then if it's material, you will lose weight.' So he tested this hypothesis, came up with 21 grams. Well, the study was not really well done, and we don't lose 21 grams, but I like this approach of just keep an open mind. I would avoid any dogmatic point of view where we would decide that consciousness needs to be such or that. This is not how it works in science. So the only thing that I'm very, very, I'm defending by all possible means is the scientific method. It's trying to confront what you think to understand with what you think you measure, but then, what is reality? Well, I can tell you for these people who experienced it, it was very real, and I think it deserves more attention, and then is the question, is this happening outside independent of any brain activity, or is it somehow linked to residual brain activity? That's another question. That's a scientific question. Currently, well, there's no evidence in favor of the cosmic consciousness or whatever alternative, but never say never. I think as a scientist, you need to be critical. You also need to be critical towards your own criticisms and so just try to advance in an area that is extremely difficult. And it makes me think of these long discussions I had with Buddhist monks, with the Dalai Lama.

[Federica]: You met the Dalai Lama?

[Steven]: Yes, yes, which through the Mind & Life Institute, which is putting together neuroscientists and, well, experts of the mind but with a Buddhist tradition.

[Federica]: Do we have a brain scan of the Dalai Lama meditating? [laughs]

[Steven]: Not yet, not yet, but many of his monks, and one in particular I appreciate enormously, is Matthieu Ricard. He is French (has a PhD, by the way, from Institut Pasteur), and then, you know, became a Buddhist and really, for decades, meditated. And that is something I, well, I have a lot of respect for, and I try to listen to him. He came here. We put him in all our machines, and that illustrated well the difficulty, because he was trying to tell me what it is like to be in this sort, that type of meditation (because there's many types), and that is not easy. Also, with the Dalai Lama, I spent a day with him asking him all possible questions. He's a wonderful person, very curious. I said I couldn't judge whether he was a good Buddhist, but I definitely appreciated him as being a good scientist. He's very, very critical, very, very curious. That's wonderful, but also at one point, it became difficult for him to talk about consciousness, and they have something, some core consciousness where then he starts speaking Tibetan, and I felt lost. It's like... I was told Eskimos have many, many words for 'white' or 'snow' or and... Well, here, they again have all these terms for consciousness where for me, not personally experiencing this, it's hard to follow, so then I can just look at my machines, but it can also be a circular reasoning problem where I'm trying to understand these machines, I'm not sure what they truly measure, looking at some modification of consciousness I'm also not really sure about. So it's difficult, but it's fascinating also to sit down and this is quite new, I think, in our field and just be very open. As long as we stick to this scientific method, I think we're good.

[Federica]: For clinical applications, I believe that some open philosophical questions are less urgent, but they are so fascinating to me that I hope you will forgive me if I spend just a few more minutes asking you about these things now. And by the way, I'm quite happy that we could have this conversation in person and not over Skype, like I sometimes do, because I get to see your office, and I see that you have some pictures of Buddha hanging from your walls and a small statue of Ganesh on your desk, so I really want to ask this question about higher states of consciousness. You say that one of the first signs of somebody being conscious is that they are awake, and being awake is normally associated with having your eyes open. So I can clap my hands just to get your attention and you will look at me, so you have your eyes open, and that's how we see that you're awake, but then there are these things that we call higher states of consciousness that are normally associated with having your eyes shut. Normally, the Buddha is represented, is depicted with his eyes closed or almost completely closed. Could you share some thoughts on this thing, the fact that being awake seems to be associated with being aware of the outside world (your eyes open, you respond to stimuli, etc.), whereas a higher level of consciousness (as we call it) may be associated with an inward experience because you have your eyes shut?

[Steven]: So for me it's difficult to talk about these higher states of consciousness. And I'm not a Buddhist, and I don't want to, you know, talk about this through the lens of some glorification of one or the other prophet, but I have learned a lot coming from this Judeo-Christian tradition, reading these Buddhist scholars, having them in our machines. Well, meditation is just training the mind, the spirit, and this is not some magical thing. We go to the gym and we see our muscles grow. It's a bit difficult to see our brain grow, but this is basically what happens. So we see changes in gray matter. We see changes in brain connectivity, and that correlates with, well, changes in our capacity to control attention, to control emotion, to become more, well, compassionate. And this is also something I like, by the way, this quite positive view on mankind and the possibility to become a better human being. That being said, I see it as my mission as a scientist to try and reduce our ignorance when we talk about consciousness. It's a very difficult question, a long way to go. I'm convinced of that. As a medical doctor, I can only try to translate that knowledge for a better care of coma survivors (and again, a lot needs to be done) and use technology, and this is very, very important. We need engineers. We need people who can think together on how to use this for clinical use. This is so wonderful to see this interaction. It makes me think also on a recent discovery, so to speak, how we can maybe increase brain plasticity, the capacity of the brain to heal itself after brain injury, which is called non-invasive electrical stimulation. So here we have the neurosurgeons putting an electrode inside the brain and putting an electrical current in these awareness networks, but that, of course, is risk, so we've been investing a lot in the past years on alternatives. And one of them is transcranial direct current stimulation, so for 20 minutes a day, some coma survivors, well-selected patients, have, at low intensity, frontal electrical stimulation, and controlled clinical trials have shown that this can be helpful. It's, again, not a miracle cure. It's not something magical. Many things we're trying to understand, but this is, again, great to see how technology, new insights, can actually change medicine.

[Federica]: We have mentioned earlier that brain death is today the criterion to determine whether somebody is dead for good or can be resuscitated, so it seems legitimate for me to draw a conclusion that is that the place of consciousness is the brain. In fact, it's not in my kidneys, or if you chop an arm of mine, I'm still alive and I'm still awake, I'm conscious, and I probably want to hit you with the other arm that I have left, but say in fact if you... Now, it's a bit crude, but if you chop my legs, if I lose all my limbs, and I'm still alive, I'm still conscious, so consciousness was not in there and there and there. So I would like to ask you: In the model of consciousness that you normally apply in your work, do you consider situating consciousness? Is that a concern at all, and is it in the brain, or is it maybe spread out all over your body? Or where I'm going with this, actually, is asking you if maybe consciousness is distributed also outside of our bodies in the environment, consciousness as being aware of the environment to the point that your consciousness is tied to the environment, is part of it, it's actually made of it?

[Steven]: So, of course, I'm biased. As a neurologist, I look at the brain, and we see that that brain is important. If I would damage your brain, well, we would see the consequence. You would have a problem to speak, problem to move. You would have, if the damage is big, you would completely lose consciousness. It would change your thoughts, perceptions, emotions. That's what I see every day in the hospital. If I change your brain activity by giving you one or the other drug or anesthetic, it will change the way you perceive, so that link is clear and it would be, I think, crazy to ignore that knowledge and the work that's been done by many, many scientists and clinicians. That being said, it would also be crazy to say it must be like that. Maybe [I said 00:43:10] there's other forces there, other whatever you call it, but then, of course, we need to make that into a falsifiable theory. If there's something out there (you can call it a waveform, energy) well, what is it? Is it electromagnetic waveform that I can measure, that I can perturb, that I can change the interaction of that, whatever it be, with that material object I can see which is the brain? And that's how I think we should proceed. If, of course, we propose, 'Well, can't it be elsewhere?' Then we need to go further. What are we talking about, and how can we change that to make, you know, predictions and to test, again, through one or the other measurement? If you say, 'Well, it can't be measured,' of course then we're done, and I think that we need to stay with an open mind but also with a critical scientific mind. That's at least what we try to do here with the team.

[Federica]: Is the level of unconsciousness of somebody in a coma an indicator of their capacity to come back, or not necessarily?

[Steven]: Not necessarily. You can have very profound coma and recover well. I could show you here surgery being done where we replace the aorta, so this big artery. To be able to do that, you need to stop the heart from beating, so you will connect the person to a heart-lung machine, but then you would even need to stop that machine. This is really very impressive. So you see a body, and you would empty that body from all its blood, you would cool it, you would give it different drugs, but then you basically have a brain no blood flow whatsoever and yet you can do your surgery of the heart and this big artery and the person afterwards wakes up and is cured from his disease and has no, if everything goes well, sequel. So this is very, very impressive. You have a very deep coma there. Right? A very, very deep anaesthesia. There's even no blood going to the brain, and yet it can be reversible. So this is like the current limit of where we are.

[Federica]: Does the sleep induced by anesthesia qualify as being in a coma?

[Steven]: No, but it's a deep coma, and yet it's fully reversible, and we see that also in pathology. But of course, when you have a lot of bleeding, a lot of damage, that is classically not a good thing, and if it's there for a long time, then, again, prognosis is less good, but so this is, you know, the whole challenge of intensive care and critical care neurology. It is to take into account, what is the cause? If it's a brain anoxia, it's different than for bleeding, for traumatic injury, if it's a child or an adult. What is the result of all these different scans and measurements that we do? So there... Well, basically, every case is different. Sometimes things are clear, and like in brain death, there is no uncertainty if the diagnosis is, of course, correct, and then there's all these different gradations and levels of uncertainty where we're trying with the team to help, again, with technology to reduce that and to make better predictors. You should know that in intensive care, people die, of course, and the majority of these deaths are the result of that decision from the team to let people die. The majority of people dying in intensive care is because we let them die. That's a very important decision and that is based on these different tests, and of course, we don't want to live in a society where we let people die when there is a chance of recovery. We also don't want to live in a society where we just continue, continue without having the courage to ask, 'Is there hope?' and create these artifacts of modern medicine where people can survive for decades but without any possibility to communicate, which is minimally conscious state, and what is that life? Is it worth living? So these are big questions. Maybe one question I have here for the listener is, please anticipate. It can happen to you tonight, and talk about it. Talk about it with your friends. Write it down. 'The day I'm in intensive care, comatose or unconscious, these are my values.' We consider death too much as a taboo. Well, one day it's going to happen, and so please think about it. Help the medical teams to make the right decisions for you, and this is how modern medicine should proceed. We're not gods. We're not supposed to make decisions without much discussion. We should just explain, 'This situation, what would this person have wanted?' And so there again, I think each and every one of us should consider what are our values and share them, identify a person of trust.

[Federica]: And don't pick a friend that will get your money when you're dead. [laughs]

[Steven]: Yes, it's rare, but of course, we need to make sure that we don't let people die because it costs a lot of money, because there is a big heritage or whatever. All the cases where I was personally involved where people act out of love, and we just need to be very transparent about what is the current reality. We should be careful not giving these people, these families, false hopes. It's very difficult. But we also shouldn't, I think, have ourselves false despair. For way too long, we've considered, 'Well, there's nothing we can do for none of these patients,' the so-called vegetative state patients. I hate that term; now we talk about unresponsive wakefulness, and we do know some of these people can recover. So it's all about these nuances. It's accepting the complexity of medical reality and trying to do best what is the case for this specific person.

[Federica]: It does concern us all, and we should be thinking about it also because it involves concepts like dignity and quality of life. There is another positive message that I encountered preparing this interview, and I was just reminded about it by a big poster outside of your door here at the office, and that is that there is life after death and that is, donating your organs. By donating your organs you can not just save one life, but you can actually save up to seven lives. Is that correct?

[Steven]: Absolutely, and so I think most of us would happily accept another organ when our kidney fails, our liver, lungs, heart, pancreas. So, well, if we want people to donate, if we want to receive an organ, well, of course, we should also think about, are we willing to give? And especially giving after death. I mean, it's a choice between being buried and being eaten by worms or being burned, cremated. So to me the choice is clear. I'm registered as an organ donor, and I see from discussing with these families when there is this dramatic situation when they lose their loved ones and we need to explain, 'Well, your husband or daughter or sister is in coma, it's irreversible, and she or he evolved to brain death, and now we can proceed to organ donation.' This is a lot of information, and sometimes they will say, 'Whoa, whoa, no. This is not true. We can't accept this.' So please, again, anticipate it. In Belgium, it's very easy. You go to the town hall and you register as an organ donor or not.

[Federica]: And what happens next? Is there like an official registry? Are you there for life automatically? Because I registered years ago, but it was so many years ago that the card they gave me to keep in my wallet is gone. I must have lost my wallet at some point in my life, and I only got my ID and bank cards back, not that card. Is there a way to know if I'm still a donor, and most of all, am I a donor everywhere or just in my home country, in all over the world, in Europe? How does that work?

[Steven]: So, well... You're not Belgian, right? So...

[Federica]: I'm not. I'm Italian and Slovenian.

[Steven]: So it's a bit difficult for you to go to the town hall, but as a foreigner, also, if you die in Belgium, you would, Belgium law would be applicable, and it's just important that, you know, at least tell it to your treating physician, tell it to your family.

[Federica]: Get a tattoo. [laughs]

[Steven]: [laughs] Well, well, by all possible means. I like just things to be discussed. I hate taboos. It helps the clinical teams. And what I also see is that families, your family, it would be, of course, dramatic to see someone die, to see someone young die, but knowing that this drama, somehow you can save lives, up to seven lives, and this, in reality, we see helps people cope. It gives some kind of meaning, and really, I think it's important that we think about it, that we make the decision, write it down, both about brain death and organ donation, but also about us being in a terrible condition, unable to express our wishes at that moment, so the only thing we can do is express them beforehand.

[Federica]: Speaking of transfers, we can transfer some organs from a body to another. That's why you can donate certain organs like your kidneys, the heart, but you cannot donate your brain. Yet. Maybe. What I would like to ask you is, do you see as a future possibility, even just on paper, as a possibility in theory, the fact of transferring consciousness from one body to another, or for what I'm concerned, from a body to a machine, something that is able to support consciousness?

[Steven]: Currently, no. We are part of the Human Brain Project (by the way, we have positions open, so we are always welcoming bright students; please apply.) That Human Brain Project is all about modeling the human brain, trying to somehow maybe put consciousness on some computer. But we should be very clear: Our brain is not a computer. Our brain is not just bits of zeros and ones. Even the quantum computers, we talk about neural networks, but this is not the brain, true neural network. So currently, we can't, by any means, transfer your thoughts, personality, emotions to one or the other hard drive or computer. Some companies make money by, well, proposing cryopreservation so you can now, after death, being kept at a very low temperature...

[Federica]: After death.

[Steven]: Yes.

[Federica]: That means after brain death.

[Steven]: Yes, or even none-brain-death criteria. People are kept just frozen. And you can do that. The problem is that currently there is no mammal that we could ever deep freeze and make conscious again, so I don't think it's a good investment. Others, again, having difficulty to accept their own mortality, would go for brain transplantation, and again, this currently is not technically feasible. There is actually one surgeon proposing this. It's planned to be done in China.

[Federica]: On humans or on animals?

[Steven]: On humans, and again, that's not a good idea, because it fails in humans, and you can basically... It's not a brain transplant. It's a head transplant, and in reality it's more a body transplant, so you would truly guillotine a person and then switch bodies, but the way this head, brain, can control that body currently needs a lot of future technological breakthroughs. So citing James Bond, never say never, but currently, well, you know, there's your consciousness. It's in your body. Probably your brain is playing a very important role there, and that's the only certainty we currently have, and we better enjoy it.

[Federica]: Thank you so much for being on Technoculture. This has been a very interesting conversation for me. I would like to keep asking you questions, but we ran out of time. Like you said, never say never; maybe we can have another chance in the future to do that. Thank you so much again.

[Steven]: You're welcome. Cheers.

[Federica]: Thank you for listening to Technoculture. Check out more episodes at technoculture-podcast.com, or visit our Facebook page @technoculturepodcast and our Twitter account, hashtag Technoculturepodcast.

Page created: December 2018

Update: April 2020

Last update: July 2021